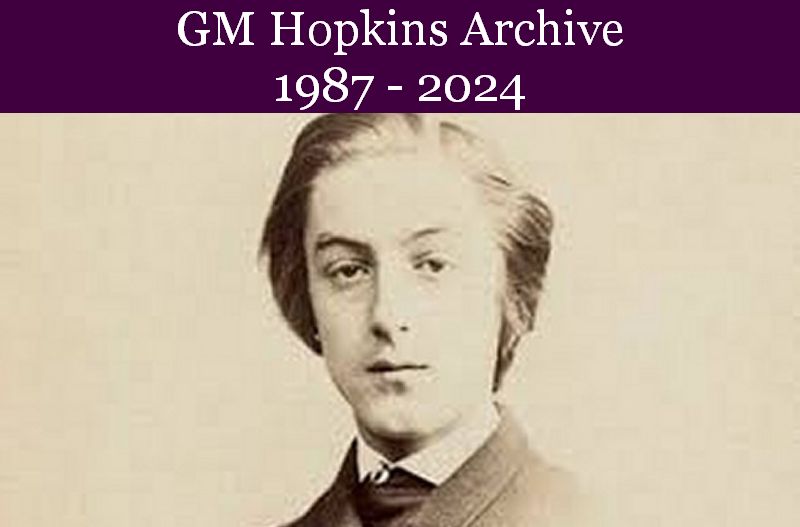

Robert Bridges - Hopkins's Friend or Foe

With A Friend Like That ….: Robert Bridges's 'Preface to Notes' in Hopkins's Poems, 1918

William AdamsonHead of English in the Centre for Languages and Philology ,

University of Ulm

Germany

... tis a good thing to make the light-footed reader work for what he gets I.A. Richards, Dial, 1926

“We expect some measure of difficulty in modern verse; indeed we are suspicious when we find none” The Listener, 1932

Every true poet, I thought, must be original

and originality a

condition of poetic genius; so that each poet is like a species in

nature […]

and can never recur. That nothing shd. be old or borrowed however

cannot be. G.M. Hopkins,

Letter to Coventry Patmore, 1886

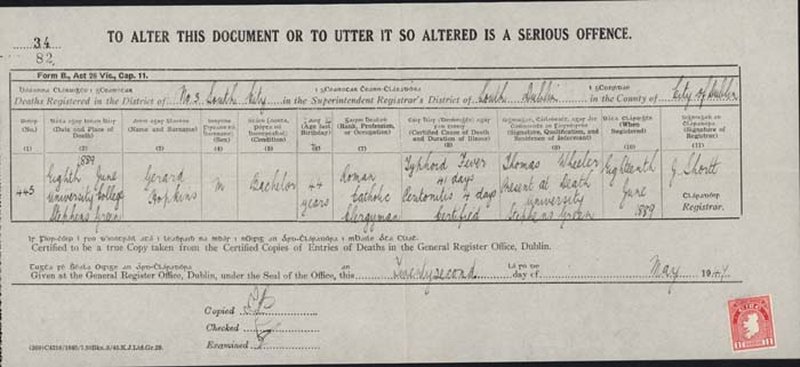

Introduction

To say that recent studies on Robert Bridges, Britain's poet laureate from 1913 until his death in 1930, are rare is perhaps overstating the issue: there is none. The last biography dates from 1992,1 with four other works dedicated to Bridges appearing sporadically between 1914 and 1962.2 However, in the nineteen seventies and eighties one man, the American critic Donald E. Stanford, devoted a great deal of time to research on Bridges, resulting in no less than seven books either authored or edited.

Stanford's most important work is arguably In the Classic Mode, the Achievement of Robert Bridges, which appeared in 1978.3 In chapter five of this work, titled The Critic, in just over two pages4 he assess Bridges' critical relationship to Hopkins, based solely upon the “Preface to Notes†in the 1918 first edition of the Poems. Stanford's exercise in apologetics is studied. He begins with the statement that Bridges took great care with the format and accuracy in the presentation of his fr in the 1920s, and that, except for an “underground iend's poems.5 Standford then asserts that the public was just barely ready for the poems backing among a few young poets in the United States and among the Imagists 1 in England, Hopkins' poetry subsequent to publication received no wide recognition until the 1930s. This last claim is in part justified and, given the limited print run, the high cost of the book, and the difficulty of obtaining a copy, perhaps not surprising.6 One further explanation for this lack of recognition, however, could equally well be the preface, as Bridges obviously did not subscribe to the generally held belief that a this should also be a preeminent advertisement for a book: the more compelling the preface, the more compelled the reader will feel to buy it. On the contrary, Bridges' prefatory remarks are not only antagonistic, but emphatically destructive, and it is a sad fact that many of the early reviews of the 1918 edition spent a disproportionate amount of time praising this very preface. As the American critic, Todd K. Bender, has astutely written:

The most extraordinary fact about Hopkins' early reputation is not that he survived thirty years of neglect, but that he survived the attention of his friend Bridges in the preface to the notes of the first edition.7

Thus begging the question what the initial reaction to the poems might have been without Bridges's preface.

Preface to Notes

But the 'Preface to Notes'8 is there: some 2,900 words in length. Initially Bridges states, reasonably enough, that as the editor of a posthumous collection he is “bounden to give some account of the authority for his text: and it is the purpose of the following notes to satisfy inquiry concerning matters whereof the present editor has the advantage of first-hand or particular knowledge. There then follows an explanation of his various sources (four9), and of the dating of the poems. We are informed that the "edition purports to convey all the author's serious mature poems; and he would probably not have wished any of his earlier poems to have been included."

Initially, Bridges touches briefly

upon the

peculiar scheme of prosody invented and developed by the author a full

account

of which, however, is out of the question

.10 Bridges seems to have

regarded the œmetrical scheme of the poems as too complex, due not

least to Hopkins's

system of diacritics. I will not pursue the point here, but simply

agree with

Robert Graves who makes the valid point that these very prosodic

features are

part of what made Hopkins a modernist and that: they had to be understood as he meant them to

be, or understood not

at all 'which is the crux of the question of difficulty' in poetry.

Hopkins

cannot be accused to trying to antagonize the reading public.11

Likely so for a number of reasons, but his modernism certainly seems to have antagonized Bridges, who writes that regarding the blemishes in the poet's style, they are and will remain what they were, continuing: Nor can any credit be gained from pointing them out. Bridges, however, is burning to do and goes back on himself immediately by stating , to put readers at their ease, I will here define them. He then singles out several areas for particular criticism: mannerism, style, oddity, obscurity, omission of relative pronoun, identical forms, homophones, rhymes, euphony and emphasis. There then follow around four and a half pages of adverse observations, against which at the end he sets some three comments of qualified praise of the qualities of Hopkins's poetry none of which is supported by example. Having listed in detail all the bad faults, he then instructs the reader that “if he is to get any enjoyment from the author's genius he 'must be somewhat tolerant of them'. He then proceeds to confuse us by straightway contradicting himself, writing that it is actually these faults that are the source of the very real relation to the means whereby the very forcible and original effects of beauty are produced. I think the obscurity here is Bridges's.

During the course of the Preface, the expectant reader, just having bought his copy of Poems, is told specifically that what he will be reading is peculiar, repellent, œobstructive, hideous, that the author indulges in freaks, that his childishness is incredible, and that his poetry is distressing, false, defective, disagreeable and vulgar or even comic, is faulty, strange, idiosyncratic, paradoxical, confused, abusive of convention, careless, obscure, odd, risible, extravagant, rude, wanton, affected, perverse, unpoetic, unfortunate and ambiguous. Indeed, the overriding criticism seems to be that of ambiguity, with the noun or its adjectival form ambiguous occurring no less than seven times. The faults would not appear to be few at all, and a less malicious, view might be that much of what Bridges regards as faults is rather, in context, the very props and struts of Hopkins's verse, a constituent part of his creativity, embodying the central ideas of his prosody.

The next area specifically singled out for censure is that of mannerism and style, Bridges writing that the poems may be convicted of occasional affectation in metaphor. He cites, as an example, Hopkins's description of hills in the poem Hurrahing in the Harvest as stallion stalwart, very-violet-sweet,12 These affectations may have upset Bridges's delicate sensitivity, however, as so often, he is condemning that which he appears to have neither the capacity nor the desire to understand.

I do not have the time to attempt to redress all the “negative†examples of Hopkins's poetry that Bridges cites in his preface, but I will just say a few words on this last censure to underline his fundamental lack of understanding of the poetry and of two of its major themes: nature and religion.

Taken within the context of the poem, the lines are a perfect example of Hopkins's ability to knit two apparently very different qualities together to create an inclusive picture of the divine in nature. The first image, stallion-stalwart, represents the resolute, unwavering faith and masculine power of the divine, counterbalanced by the compound adjective very-violet-sweet, symbolising the gentle and compassionate feminine aspect of Christic nature. Violet is often used in art as the colour of the Virgin's robes, and as a flower, it symbolises renewal.13 Violet is also the colour at the end of the visible spectrum of light between blue (the azurous hung hills of the previous line) and invisible ultraviolet, that is to say the link between the perceived, natural world and that of the immortal, invisible light14 of the Spirit. Had Bridges had less conceit and more humility, he might have taken the time to look at Hopkins's lines with a more sensible and understanding, and a less jaundiced eye.15

Nevertheless, Bridges was offended by what he terms Hopkins's efforts to force emotion into theological and sectarian channels,16 which he terms a perversion of human feeling. However, it is hard to comprehend what exactly it is that Bridges is objecting to; he seems to have misunderstood, or wilfully ignored the context of Hopkins's writing. Hopkins was a religious poet; some measure of theology or sectarianism should, therefore, not come as a surprise.

And this is one of the main weaknesses of Bridges's Preface to Notes: his complete failure to provide the reader with any real context, with any measure of information about who Gerard Hopkins was. There is no mention of his faith, his Catholicism, his being a Jesuit, his beliefs in short, all those things that inspired him as a man and as a poet. It is, I think, more the transgression of religion into the poetry that Bridges is referring to when he writes that these transgressions of taste “more repel my sympathy than do all the rude shocks of his purely artistic wantonness. The simple fact is, as the poet Austin Clarke wrote, that an elementary knowledge of Roman Catholicism and its spiritual training would clear many of Hopkins's apparent obscurities.17

This artistic wantonness is inclusive of Bridges's ensuing criticism, the oddity and obscurity of Hopkins' style which, the Preface tells us, a reader must have courage to face and even in some measure condone. Hopkins, Bridges seems to be saying, is running the risk not only of inaccessibility, but of being incapable of recognising his own purpose, thus opening himself up to both the derision and puzzlement of the poetic world.

I will here define them: they may be called Oddity and Obscurity; and since the first may provoke laughter when a writer is serious (and this poet is always serious), while the latter must prevent him from being understood (and this poet has always something to say), it may be assumed that they were not a part of his intention.

Indeed, Bridges' foremost criticism is the unintelligibility or ambiguity which, in his opinion, imbue Hopkins' poetry. But here Hopkins had offered him some valuable advice that advocates a common sense approach to the reading of poetry: it is obscure do not bother yourself with the meaning but pay attention to the best and most intelligible stanzas.19 Something that Bridges in his obstinate wisdom took no heed of. Why, Hopkins writes to him in a later letter, sometimes one enjoys and admires the very lines one cannot understand.20

Yet another area singled out for critical appraisal under the header oddity and obscurity is what Bridges refers to as Hopkins' grammatical liberty, specifically his unconventional sentence structure due mainly to the use of ellipses, particularly the omission of the relative pronoun. He writes proscriptively that, he was not sufficiently aware of his obscurity, he would never have believed that, among all the ellipses and liberties of his grammar, the one chief cause is his habitual omission of the relative pronoun; and yet this is so.21

One example Bridges chooses is the line O Hero saves from The Loss Of The Eurydice stating definitively, and with no little hyperbole, that to omit a 'that' between Hero and saves is an abuse of licence beyond precedent.

Hopkins' poetics is based to a great degree on the idea that all unnecessary words should be omitted and a line reduced to its most energetic and economical form (sometimes, in the most extreme case, down to three or four key words). This forces the reader to generate syntactical connections if he is to make the text intelligible. The ambiguity caused by the exclusion of such particles as relative pronouns, prepositions and conjunctions means that the additional information is always implied and must be negotiated by the reader in order to discover the hermeneutic possibilities in the poet's often oblique semantics. The aim of linking seemingly incompatible words in Hopkins' poetry, as in all good poetry, is to disrupt consciously the readers' expectations of meaning. This ambiguity is one of the means by which verse achieves its effect, in other words in this instance by making the reader identify and contend with two or more potentially contradictory meanings that may in fact turn out to be complementary.

But Hopkins was a far too serious and self-exacting poet to indulge himself in a capricious poetics of ambiguity, although he readily agreed that his verse could be challenging due to his principal intention: to strive to reveal the inscape 22 of poetry, that unified complex of characteristics that gives each thing its uniqueness and that distinguishes it from other things. He was also fully aware of the problem of the perceived “oddness†of his verse and understood it to a greater extent than many of his critics. No doubt my poetry errs on the side of oddness, he wrote to Bridges, continuing, But as air, melody, is what strikes me most of all in music and design in painting, so design, pattern, or what I am in the habit of calling inscape is what I above all aim at in poetry. Now it is the virtue of design, pattern, or inscape to be distinctive and it is the vice of distinctiveness to become queer. 23

Hopkins dared to challenge the moribund restrictive lexical and syntactical conventions of 19th century: this essential propriety, as Bridges terms it.

Bridges' dogmatic approach to the propriety of language, by contrast, is pathologically obsessive; he approaches

poetry as

if it were prose, and seeks to apply the same rules governing

transparency of

meaning. In his Preface, he writes pompously that such ambiguity or momentary

uncertainty destroys the force of the sentence this may be true for prose, but surely not for poetry. Indeed, as

James

Milroy has pointed out, Hopkins

took such a positive joy in these ambiguous placings of words that the

habit

must be counted as one of the guiding principles of his art. 25 And

this is just how these syntactical innovations should and must be

viewed: as

integral to precisely the

understanding and interpretation of Hopkins' poetry.

Conclusion

In context, Bridges is a man of his time, a Victorian, and he has the tastes and habits of a Victorian. In retrospect we do not expect Bridges to have changed, simply that he should have been prepared to accept and recognise that change in poetry, as indeed in all things, is a necessary and invigorating process. His fault was that once having formed his opinions, he approached poetry with the conviction that he alone had the right to pass judgement over wrong and right convention. He condemned originality and change, doggedly holding tightly to 19>th century lyrical forms whilst the world around him was hurtling excitedly on with poets such as Eliot (1922 The Wasteland) and Pound (1917-1919 the Four Cantos). This was more the world of Hopkins, a complete original in his own time, a man who, as F.R. Leavis has put it, possessed “a vigour of mind that puts him in another poetic world from other Victorians. It is a vitality of thought, of vigour of thinking intelligence, that is at the same time a vitality of concreteness.26

W.H. Gardiner has pointed out that Bridges' prefatory comments reveal curious lack of understanding, a mistrust, against which Hopkins himself vigorously protested.Indeed, it is as if Bridges regarded Hopkins' verse as somehow subversive and his dissident practices to be regarded with the deepest suspicion as presumptious [sic] jugglery. This is, of course, not surprising given Bridges' fundamentally conservative attitude, and it is perhaps therefore to be expected that he should have complained so often in his letters to Gerard about the peculiarity of his poetry, which must inevitably have given rise to a decided lack of sympathy between the two men with regard to literary convictions. Bridges naturally enough for Bridges, one Hopkins biographer tell us, complained about the unintelligibility. Going on to comment: [h]ad Hopkins been egoistic he might have answered with Ruskin's assertion that Excellence of the highest kind without obscurity cannot exist.

In his introduction to Austin Clarke Collected Poems, the critic Christopher Ricks refers to a line in one of Clarke's poems. A Jocular Retort that contains the words: hold back meaning,commenting,

And why is it a good thing to hold back meaning? Because, if the poet isn't careful, meaning has a way of too insistently shouldering its way in, so that we readers then have the meaning but miss the experience.30

In Gerard Hopkins' poetry, Robert Bridges appears to have missed both.

Notes

- 1. Catherine Phillips, Robert Bridges: A Biography (Oxford: Robert Bridges; A Critical Study (London: Martin Secker, 1914), Albert Guérard’s Robert Bridges: A Study of Traditionalism in Poetry (Cambridge, Mass., 1942); Edward Thompson’s Robert Bridges 1844-1930 (Oxford: OUP 1944); John Sparrow’s Robert Bridges (London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1962)

- 2. Donald E. Stanford, In the Classic Mode the Achievement of Robert Bridge (1978). He is also the author of Robert Bridges and the Free Verse Rebellion (1971), the editor of Robert Bridges Selected Poems (Cheadle Hulme: Carcanet Press, 1974) and editor of the selected letters of in two volumes.

- 3. As compared to ten pages on Keats and seven on Shakespeare.

- 4. Often as interpreted by Bridges, rather than following Hopkins’s original manuscripts.

- 5. The original number of copies printed by the Oxford University Press was 750 sold in 1918 for 12s. & 6d. per copy, in today’s (2017) prices 40 or €47. This obviously had a direct effect on the marketability of the book, along with the publisher’s seeming reluctance to supply bookshops with copies. The edition did not sell out completely for ten years.

- 6. Todd K. Bender, Gerard Manley Hopkins: The Classical Background and Critical Reception of his Work (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1966) p. 5.

- 7. http://www.bartleby.com/122/101.html. Due to their frequency, all further quotations from the Preface in the main body of the text will not be directly referenced in the footnotes.

- 8. The sources are distinguished as A,B,D, and H. Source A is Bridges’s own collection of Hopkins’s poetry; source B is a MS book into which Bridges’s and copied certain poems of which Hopkins had not kept a copy; source D is a collection of Hopkins’s letters to Canon Dixon; source H is the bundle of posthumous papers that came into my hands at the author’s death.

- 9. The real reason, of course, as Mariani tells us, was that the postponed printing the collected poems until he had his own method of prosody recognized separately from Gerard’s. Paul Mariani, Gerard Manley Hopkins: A Life (New York: Viking Press, 2008) p. 428.

- 10. Robert Graves, The Common Asphodel (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1949) p. 99.

- 11. James Milroy, on this particular “mannerism”, which he says is actually the essential Hopkins at his best, writes that The collocation of stallion and feeling that the words, being similar in sound, must be etymologically related. He would probably believe that stall (a place to stand) was the first element of them both. Modern etymological opinion does in fact relate both words to the root represented in Latin by sto, stare (to stand). See Milroy, The Language of Gerard Manley Hopkins (London: Deutsch 1977), p. 42.

- 12. Called the Flower of Modesty because it hides its flowers in the heart-shaped leaves. Also called Our Lady's Modesty because it was said to have blossomed when Mary said to the Angel Gabriel, who had come to tell her she was to bear the Son of God, "Behold, I am the handmaid of the Lord."

- 13. The monks of the Middle Ages called Viola tricolor, common in Europe, the Herb of the Trinity (herba trinitatis) because they saw the symbol of the trinity in their three colors.

- 14. Laura Riding and Robert Graves make the following comment on this subject: “Why cannot what Dr. Bridges calls a fault of taste [...] be, with the proper sympathy for Hopkins’s enthusiasm, appreciated as a phrase >reconciling the two seemingly opposed qualities of mountains, their make, animal-like roughness and strength and at the same time their ethereal quality under soft light for which the violet in the gentle eye of the horse makes exactly the proper association?” In: A Survey of Modernist Poetry (London: Heinemann, 1927) p.3.

- 15.This, incidentally, is one of Bridges’s constant bugbears, that Hopkins was in some way hamstrung by the requirement to indulge Catholic theology. The point has to be made that recognizing that a poem is intrinsically religious in its message should in no way hinder our appreciation of its value as a work of art. See, for example, “Glory Be To God for Dappled Things”.

- 16. Austin Clarke, “Review of The Poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins by E.E. Phare in: Gregory A. Schirmer (ed.) Reviews and Essays of Austin Clarke (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe, 1995), p. 183.

- 17. Robert Bridges, Preface to Notes: http://www.bartleby.com/122/101.html.

- Catherine Phillips (ed.), Gerard Manley Hopkins Selected Letters (Oxford: OUP, 1990). To Robert Bridges. St Beuno’s, St Asaph. Aug. 21 1877.

- 18. Ibid., To Robert Bridges. Stonyhurst College, Blackburn. May 13 1878. We are reminded of Ruskin’s comment on art in Book IV of Modern Painters that “all great work is indistinct; and if we find, on examining any picture closely, that it is all clearly to be made out, it cannot be, as painting, first-rate. There is no exception to this rule. Excellence of the highest kind, without obscurity, cannot exist.

- 19. Robert Bridges, Preface to Notes: http://www.bartleby.com/122/101.html.

- 20. Hopkins’s inscape is also essentially religious, with the inscape of a thing showing us why God created it. Each mortal thing does one thing and the same: myself it speaks and spells,/ Crying Whát I dó is me: for that I came. – “As Kingfishers Catch Fire”.

- 21. Catherine Phillips (ed.), op. cit. Letter to Robert Bridges, February 15, 1879.

- 22. The use of this word alone is interesting and tells us much of Bridges’s own mindset and just how seriously he took the rules of propriety: if you did not conform, you were considered an outcast from proper society.

- 23. James Milroy, The Language of Gerard Manley Hopkins (London: Deutsch 1977) p. 9.

- 24. F.R. Leavis, The Common Pursuit (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1962)

p. 48. - 25. W.H. Gardner, Gerard Manley Hopkins: A Centenary Celebration (London: Secker & Warburg, 1944) pp. 208 – 9.

- 26. Hopkins’ response to this was a definite “No”, going on to point out that the word “presumptious”, as written by Bridges for “presumptuous”, “is not English”.

- 27. Gerard Roberts, Gerard Manley Hopkins: A Literary Life (London: Macmillan 1994) p. 64.

- 28. Christopher Ricks, Introduction to: R. Dardis Clarke (ed.) Austin Clarke Collected Poems (Manchester: Carcanet, 2008) p. xv.

William Adamson Examines Bridges and Hopkins celebrated Friendshop

William Adamson:Robert Bridges Preface to Hopkins' Poetry