Gerard Manley Hopkins in Dublin

Robert A. Smart,

Quinnipiac University

USA.

This Lecture was given at The Hopkins Literary Festival July 2012

Writing in blood, writing in flesh—even when the formulas are

figurative, they represent a special access of the authoritative,

inalienable, and immediate; the writing of blood and flesh never lies.

What the writing gains in immediacy, though, it loses in denotative

range, since writing that cannot lie is only barely writingEve Sedgwick, The Coherence of Gothic Conventions

The title for my talk today comes from critic Eve Sedgwick’s analysis of Gothic conventions and personal history, and while I will make a small claim near the end for a Gothic dimension in Hopkins’ life, I wanted rather at this beginning to focus on language. Most especially, I have been drawn for this project to Hopkins’ struggle with language, particularly with regard to the shifting epistemologies of words when they are pulled from their demotic work into a poetic function. In clear anticipation of his modernist brethren (1 ),

Hopkins dealt with language differently than did his contemporaries, most of whom wrote from a transcendent view of language. In this view, language is a thin veil separating us from the world of phenomena, what Matthew Arnold called the poet’s “forts of folly (2), that aspire to materiality but in the end are consigned to the figurative realm. Many of the most illuminating exchanges between Robert Bridges and Hopkins about Hopkins’ poetry arc around this difference: Bridges suggesting that Hopkins’ “experiments” in language be made more referential and Hopkins responding in terms that describe how image, word, music and syntax combine to suggest “plenty meant.” My argument is that his posting to University College in Dublin for the last five years of his life severely tested his mature aesthetic and eventually led him from creative crisis through to creative resolution. Hopkins understood that poetic language especially has epistemological autonomy, something that was addressed most recently by the indefatigable Terry Eagleton with reference to Hopkins:

“To regard language as autonomous, then, is not a question of severing it from the real. […] On the contrary, to take this view of language is to grant its full materiality, rather than to treat it as a pale reflection of something else .” (157)

What interests me in this discussion is how Hopkins’ understanding of the autonomy of language affected his working and evolving aesthetic, most familiarly described by his notions of inscape, instress and sprung rhythm. It’s my sense as an admirer of Hopkins’ work that these terms, while they are tied most often to his linguistic experimentation, are most accurately understood as a nearly scientific methodology devoted to wringing from language what Hopkins described in his final poem to his oldest and dearest friend Robert Bridges as the “sweet fire the sire of muse.” His method is scientific in the sense that it is always probing, dislodging, juxtaposing and splicing the language to make words stand by themselves as objects of understanding and knowledge, as they also point inwardly to a sustained sense of the world they are tethered to. This probing aesthetic, this effort to create poetic objects that are tuned to what he called “species or individually-distinctive beauty of style,”—“inscape”—was ongoing, insistent and frustrating, particularly once he arrived in Dublin in February 1884.

In Hopkins’ aesthetic, the poem was not a lens to look through, but a thing of beauty purposed to recalibrate our inner sight that we might glimpse “God’s Grandeur.” It’s worth remembering Hopkins’ longstanding love of words, dialects and languages, ranging from learning Welsh to collecting expressions of Hiberno-English for the font-weight: bold;"English Dialect Dictionary. The vessel for this poetic science was the sonnet, a form that he wrestled with and against throughout his later years, especially after he started his Irish sojourn. In 1888, Hopkins wrote somewhat playfully to Bridges that for some time “now years . . .I have had no inspiration of longer jet than makes a sonnet” (White 452). Hopkins’ readers have long noted the mismatch between some of his poetic language, which is expansive, and the patterned closeness of the sonnet form. Norman White refers in his biography of Hopkins to the poet’s “awareness of a disparity between his material and the capacity of the sonnet form ,” and no less an eminence than Nobel laureate Seamus Heaney notes that Hopkins’ poetry is “fretted ,” (8) as though without some kind of external scaffolding, the words would spill out onto the page, driving wildly (“fecund”) towards some dimly seen end.

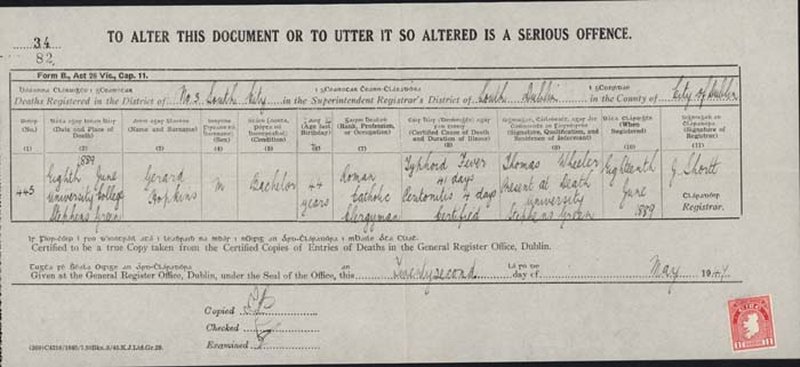

In the period covered by this talk, 1884-1889, Hopkins struggled mightily against the sonnet form he chose. From “Spelt From Sibyl’s Leaves” (1884) through to his final poem, , we can see an evolving aesthetic which is driven by Hopkins’ sense that since his arrival in Ireland, he had become “time’s eunuch” whose creative fire had nearly gone out. By the time Hopkins sent “To R.B.” to his friend, one can sense in its orderly lines an acceptance of something new, a realization that the despair into which his time at University College had pushed him could become a new way of working. He was likely sick with typhoid when this poem was written and while a new understanding of his creative process might have struck Hopkins in this final year, we can see little of what it might produce in this final poem.

This roughly five year working period includes the so-called “sonnets of desolation” Dr. Gardner’s phrase) or the “dark sonnets,” by which is meant those finished poems—and there are few of these, and unfinished fragments which appear to be driven by Hopkins’ increasing sense of futility and depressive pessimism (what White terms Hopkins’ “Dublin fatalism ”) which characterize so much of his late correspondence. Hopkins’ time in Dublin was arguably the most unhappy of his life. He thought that his students were plodding, that his colleagues were narrow minded and parochial, and that the formerly grand city of Dublin had become a rundown slum. His closest colleagues thought him eccentric and precious: he suffered from eczema and had a special soap to deal with it, and the early waking hour (5:30 am) for the Jesuit community at University College was most likely extended by a half hour because Hopkins had so much difficulty waking up. Students regularly ragged him, something he did not always notice, and acquaintances thought him aloof and distant. As an English convert to Catholicism living in Ireland, Hopkins found a place on neither side of the most important issues of the time, most especially the fraught relationship between England and her oldest and most contentious colony. W.B. Yeats spoke for most of his contemporaries when he wrote that Hopkins was “most of whom remained from his years at Oxford, he was kind, gentle, intellectual and sensitive, but outside these few contacts and his family, he was viewed with suspicion and distance.

Little wonder that by 1886, Hopkins wrote poignantly:

To seem the stranger lies my lot, my life

Among strangers. Father and mother dear,

Brothers and sisters are in Christ not near

And he my peace my parting, sword and strife.

England, whose honour O all my heart woos, wife

To my creating thought, would neither hear

Me, were I pleading, plead nor do I: I wear-

y of idle a being but by where wars are rife.

I am in Ireland now; now I am at a thírd

Remove. Not but in all removes I can

Kind love both give and get. Only what word

Wisest my heart breeds dark heaven's baffling ban

Bars or hell's spell thwarts. This to hoard unheard,

Heard unheeded, leaves me a lonely began.

It’s not that others seem like strangers to the speaker in the poem, but that he is the stranger; this is a poem that works as a mirror does, offering the poet a cold, unsentimental view of himself as he appears to others.

The sonnet ends, Norman MacKenzie writes, “with a great cry of frustration as he thinks of the many inspirations for poems . . . which had come to nothing . . ” (180). This creative frustration and lack of creative production is a marked trope of Hopkins’ work during the Dublin years, leading the poet again to characterize himself in 1889 as a “straining eunuch” (White 445). In my reading of this period, this fear of creative sterility is the major concern of a powerful poetic personality in exile. Between “Spelt From Sibyl’s Leaves,” which is a barely contained excursus on the threat of annihilation, to the three final sonnets, each of which concerns the paucity of creative inspiration and the difficulty of bringing small inspiration to a fruitful end, we can see Hopkins slowly negotiate a turn in his self assessment as a poet. This significant turn is where I would like to shift my attention for a moment.

By 1886, Hopkins feels himself to be “a lonely began,” a poet with little to show for his creative desire and poetic passion. He is mostly alone, overworked and is weighed down by what he feels is a bleak life in a bleak place. When we examine the language of “Spelt From Sibyl’s Leaves,” we can discern much of his evolving poetic method. In his presentation letter to Bridges, Hopkins admits that “Spelt From” is the “longest sonnet ever made . . .longest by its own proper length, namely by the length of its lines; for anything can be made long by eking, by tacking, by trains, tails and flounces,” (Mariani 371) suggesting that he was well aware of how this new poem provided a test of the sonnet form, even if (as Bridges suggested) it was a “caudated” sonnet .

EARNEST, earthless, equal, attuneable, ' vaulty, voluminous, … stupendous Evening strains to be tíme’s vást, ' womb-of-all, home-of-all, hearse-of-all night.

Her fond yellow hornlight wound to the west, ' her wild hollow hoarlight hung to the height

Waste; her earliest stars, earl-stars, ' stárs principal, overbend us,

Fíre-féaturing heaven. For earth ' her being has unbound, her dapple is at an end, as- tray or aswarm, all throughther, in throngs; ' self ín self steedèd and páshed—qúite Disremembering, dísmémbering ' áll now.

Heart, you round me right

With Óur évening is over us; óur night ' whélms, whélms, ánd will end us.

Only the beak-leaved boughs dragonish ' damask the tool-smooth bleak light; black,

Ever so black on it.

Óur tale, O óur oracle! '

Lét life, wáned, ah lét life wind

Off hér once skéined stained véined variety ' upon, áll on twó spools; párt, pen, páck

Now her áll in twó flocks, twó folds—black, white; ' right, wrong; reckon but, reck but, mind

But thése two; wáre of a wórld where bút these ' twó tell, each off the óther; of a rack

Where, selfwrung, selfstrung, sheathe- and shelterless, ' thóughts agaínst thoughts ín groans grínd.

This is a freighted sonnet, loaded with at least three varieties of Hopkins’ wordplay: barely differentiated lists of words that are leaned against each other to create new contexts for the line (“EARNEST, earthless, equal, attuneable, ' vaulty, voluminous, … stupendous”); compound inventions which link nouns to properties he associates with those nouns in this new context (“womb-of-all, home-of-all, hearse-of-all night”), and plain invented words which have accrued meaning from the recalibrations of context in the poem (“selfwrung, selfstrung, sheathe- and shelterless”). Working with these syntactic turns, “sleights of word” Seamus Heaney calls them, are the more familiar techniques from his earlier work, verbs used as nouns and vice versa, repeated words with different meanings in the repetitions, etc.

You can hear the groaning of the poem’s form as it seeks to contain the multiplying language, heavy with nouns, adjectives and moving across the space in a sprung cadence that resists the English rhythms of memory. Critic William Joseph Rooney reached the conclusion several years ago that weighted by all these lingo-technics the poem amounts to “the clash of elements unassimilated to a whole—the rococo of conspicuous consumption ” (510). By the time we reach the significant turn in line 10 “Óur tale, O óur oracle!), it’s difficult to remember that the speaker’s apocalyptic vision is derived from viewing a sunset in which the swallowing of the light, the sun, leads to a powerful image for creation: the division of chaos into black and white, right and wrong, image and thought. The key shift here, it seems to me, is that destruction leads to creation, a decidedly Eastern leaning aesthetic shift.

When in July 1888 Hopkins finished “That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire,” the threatened dissolution of self which threads through both his poetry and his meditations of his middle period, has begun to move toward a persistent and insistent creative drive: In a flash, at a trumpet crash, I am all at once what Christ is, ' since he was what I am, and This Jack, joke, poor potsherd, ' patch, matchwood, immortal diamond, Is immortal diamond . The repeated final words in this last stanza point to a resilience in Hopkins’ poetic life that has been missing since early 1884.

As we move into the three final sonnets of his life, all written between March and April 1889, we begin to sense a difference in the position of the poet regarding his method and his work. In “Justus quidem tu es, Domine” (Thou are indeed just, Lord), we find a much more orderly sonnet than in the previous examples I have discussed, and we discover a strangely transcendent resolve:

Thou art indeed just, Lord, if I contend

With thee; but, sir, so what I plead is just.

Why do sinners’ ways prosper? and why must

Disappointment all I endeavour end?

Wert thou my enemy, O thou my friend,

How wouldst thou worse, I wonder, Than thou dost

Defeat, thwart me? Oh, the sots and thralls of lust

Do in spare hours more thrive than I that spend, Sir, life upon thy cause.

See, banks and brakes Now, leavèd how thick! lacèd they are again

With fretty chervil, look, and fresh wind shakes

Them; birds build – but not I build; no, but strain,

Time’s eunuch, and not breed one work that wakes.

Mine, O thou lord of life, send my roots rain.

Here is “time’s eunuch” calling upon God to make him pregnant, not the last time that the creative act is framed in sexual terms. The “roots” are there, we note, and simply require divine nourishment to blossom. The poem has the sound of a plaint—why is all around me fecund and multiplying effortlessly (“Oh, the sots and thralls of lust/Do in spare hours more thrive”) while all my toil and efforts seems to come to naught (“Than I that spend,/Sir, life upon thy cause”). But the end of the sonnet is not bleak, not despondent, but mostly hopeful. In addition, the poetic imagination in the poem is not inert matter waiting to be made quick by the divine hand; it only needs the merest shower to blossom.

Bibliography

- American poets Hart Crane and Wallace Stevens are the most likely of these modernist descendants.

- From “The Last Word”

- See his long gloss on one of his “Welsh” poems, “Walking by the Sea,” in White, page 278.

- Terry Eagleton, The Event of Literature. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012. The recent discovery of the Higgs boson particle would have almost certainly fascinated Hopkins, who searched for its equivalent in the language of his poems. The New York Times described the recently discovered particle as “a cosmic molasses that permeates space and imbues elementary particles that would otherwise be massless with mass." This “cosmic molasses,” I would argue, is precisely what Hopkins sought in his poetry.

- Terry Eagleton, The Event of Literature. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012.The recent discovery of the Higgs boson particle would have almost certainly fascinated Hopkins, who searched for its equivalent in the language of his poems. The New York Times described the recently discovered particle as “a cosmic molasses that permeates space and imbues elementary particles that would otherwise be massless with mass." This “cosmic molasses,” I would argue, is precisely what Hopkins sought in his poetry.

- “There are eighty-nine of Hopkins’ contributions in the six volumes of the EDD, seventy-five of them in volume I (A-C), making it likely that his lists for the remaining five volumes have been lost or were thrown away at his death” (White 437).

- Norman White, Hopkins: A Literary Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

- Seamus Heaney, The Fire I’ The Flint: Reflections on the Poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1974 (For The British Academy, London).

- Page 439.

- In Paul Mariani’s affective biography of Hopkins, Yeats is quoted as saying in a comparison of Hopkins with his friend Bridges that Hopkins was “the way out of life” while his friend was “the way into life.” Paul Mariani, Gerard Manley Hopkins: A Life. New York: Viking/Penguin Books, 2008, page 371.

- Norman H. MacKenzie, A Reader’s Guide to Gerard Manley Hopkins, 2nd Ed. Ed. by Catherine Philips. Philadelphis, PA: St. Joseph’s University Press, 2008.

- Creative and spiritual annihilation as well as physical annihilation.

- Fr. Hopkins should be the patron saint of all English teachers who are obliged every few weeks to grade stacks of papers and examinations.

- A caudated sonnet is an extended sonnet via the addition of a coda. Hopkins was an early practitioner of this form, as he was for the curtal sonnet, a Hopkins invention, which is a shortened Petrarchan sonnet form. “Ash Boughs” and “Pied Beauty” are examples of the latter.

- William Joseph Rooney, “’Spelt From Sibyl’s Leaves’: A study in Contrasting Methods of Evaluation.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. Vol. 13. No. 4 (June, 1955), pp. 507-519.

- On the stone plaque marking Hopkins in Westminster, set between T.S. Eliot and W.H. Auden, is “emblazoned the words: ‘Immortal Diamond’” (Mariani 433).

Hopkins Literary Festival Lectures July 2012

Clinical Analysis and Gerard Manley Hopkins:Hopkins in Dublin