Hopkins' Terrible Sonnets - A Reassessment

Robert Smart,

Quinnipiac University

USA

This Lecture is based on a Lecture given at the 34th Hopkins Festival July 2017

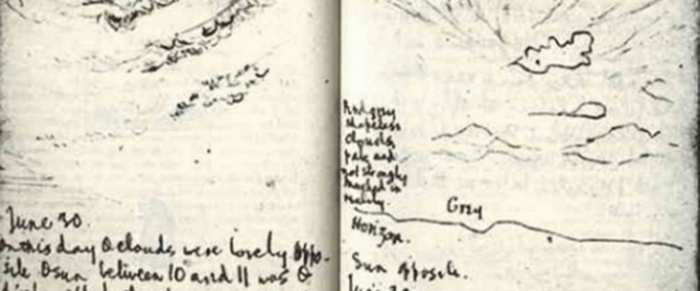

My specific interest in the problem (so-called) of Hopkins' Terrible Sonnets was rekindled recently by two unconnected events. First was my reading of a close and admired friend's manuscript on Hopkins' work in order to provide an introduction for it. Making my way through my colleague's cogent and personal assessments of Hopkins' life and work brought me round to the precise meaning of those six poems we call the terrible sonnets.1 The second impetus was a chance meeting I had one morning while walking my dog, Rocky, in our neighborhood. I ran into one of my neighbors, also tethered to a pooch, who when I spoke of my interest in Hopkins looked up at the greying sky and recited Carrion Comfort from memory, noting that it was always one of his favorite poems. He is a professor of Classics at Wesleyan University and his interest in this poem, he explained, grew from a seminar on Hopkins and Modernism that he took while completing his Ph.D. at Catholic University.

There I was, two clear signs that these six poems written between 1885-86 warranted some attention from me, and so here I am now, presenting to all of you the results of my rumination. I have two claims in this talk: first, that this brace of poems does not reflect a spiritual failure on Hopkins' part, a final anguished and unanswered call for connection with his god. Nor are the poems an expression of deep personal depression, although the underlying modus in the poems does brush up against this particular tendency in our young poet. Secondly, I want to make the case, or at least suggest a means to make the case that the poems in fact more represent an aesthetic crisis, a period in which Hopkins' reliance on a received, neo-Romantic lexicon to express his grasp of God's work needed to change as his materials and self-understanding grew.

Emersonian Definition of Nature

In a way, this last point is the most complicated one to make since it involves an Emersonian redefinition of Nature (large N) as nature (small n), a movement away from a metaphorical use of Nature and toward an acceptance of nature as it presents itself to the poet, unguarded by the rhetorical function of the language 2.

Getting past Nature large requires its personalization into nature small, allowing the poet's systematic use of this imagery to function as a new and very personal means to connect with God in the world. This next passage is from Emerson's famous essay On Nature (1836) which identifies what Nature, large 'N'means:

Nature never wears a mean appearance. Neither does the wisest man extort her secret, and lose his curiosity by finding out all her perfection. Nature never became a toy to a wise spirit. The flowers, the animals, the mountains, reflected the wisdom of his best hour, as much as they had delighted the simplicity of his childhood. When we speak of nature in this manner, we have a distinct but most poetical sense in the mind. We mean the integrity of impression made by manifold natural objects. It is this which distinguishes the stick of timber of the wood-cutter, from the tree of the poet. The charming landscape which I saw this morning, is indubitably made up of some twenty or thirty farms. Miller owns this field, Locke that, and Manning the woodland beyond. But none of them owns the landscape. There is a property in the horizon which no man has but he whose eye can integrate all the parts, that is, the poet.'Ralph Emerson (1836)

Emerson's idea is of Nature, capitalized, ready to drive metaphor (property in the horizon) into the work of the poet. This view, I would argue, is one that Hopkins inherited as a late Victorian poet, and one that he would need eventually to subvert, to pull away from and recast into a much more personal and powerful lexicon for the worship that God demands of him.

The simple truth in this case is that Nature as utilized by the Romantics has little to do with 'real'nature as the average human being encounters it, a point made by Emerson in 'On Nature. This transition for Hopkins was dark, and in his own words, came like inspirations unbidden and against my will 3 (Walker 175) [letter to Bridges 1 September 1885], but its fruits were manifestly good and led, I believe, to a certain spiritual and aesthetic resolution that we hear most clearly in the poems written between 1886 and 1889, the year of his death.

This transformational shift in Hopkins' aesthetic is perhaps best illustrated by the imagistic difference between a mature, earlier poem like God's Grandeur'(1877) which utilizes a palette of essentially Romantic nature images, most especially in the second stanza:

The world is charged with the grandeur of God.

It will flame out, like shining from shook foil;

It gathers to a greatness, like the ooze of oil

Crushed. Why do men then now not reck his rod?

Generations have trod, have trod, have trod;

And all is seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil;

And wears man's smudge and shares man's smell: the soil

Is bare now, nor can foot feel, being shod.

And for all this, nature is never spent;

There lives the dearest freshness deep down things;

And thougwent

Oh, morning, at the brown brink eastward, springs--

Because the Holy Ghost over the bent

World broods with warm breast and with ah! bright wings.

And a later poem written after the critical lacuna of 1885-86, like That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire and of the comfort of the Resurrection, in which the aesthetic distance imposed by the traditional Late

Romantic lexicon is crossed and the new language is lashed to the

purpose of constructing a renewed connection with God in his world.

That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire and of the Comfort of the Resurrection

Cloud-puffball, torn tufts, tossed pillows | flaunt forth, then chevy on an air-

Built thoroughfare: heaven-roysterers, in gay-gangs | they throng; they glitter in marches.

Down roughcast, down dazzling whitewash, | wherever an elm arches,

Shivelights and shadowtackle Ãn long | lashes lace, lance, and pair.

Delightfully the bright wind boisterous | ropes, wrestles, beats earth bare

Of yestertempest's creases; | in pool and rut peel parches

Squandering ooze to squeezed | dough, crust, dust; stanches, starches

Squadroned masks and manmarks | treadmire toil there

Footfretted in it. Million-fuelèd, | nature's bonfire burns on.

But quench her bonniest, dearest | to her, her clearest-seld spark

Man, how fast his firedint, | his mark on mind, is gone!

Both are in an unfathomable, all is in an enormous dark

Drowned. O pity and indig | nation! Manshape, that shone

Sheer off, disseveral, a star, | death blots black out; nor mark I

Is any of him at all so stark

But vastness blurs and time | beats level.

Enough! the Resurrection, A heart's-clarion!

Away grief's gasping, | joyless days, dejection.

Across my foundering deck shone

A beacon, an eternal beam. | Flesh fade, and mortal trash

Fall to the residuary worm; | world's wildfire, leave but ash:

In a flash, at a trumpet crash,

I am all at once what Christ is, | since he was what I am, and

This Jack, joke, poor potsherd, | patch, matchwood, immortal diamond,

Is immortal diamond.

In between these two moments in Hopkins' oeuvre, lie the terrible sonnets, in which according to Robert Walker, 'imagery relating to and recognizing the external world is lost, replaced by an inward-looking and private solipsism; what Hopkins creates is an internal landscape'(178). Part of my argument is that this internal landscape was and still is the key to understanding the critical center of Hopkins' aesthetic crisis and our passage into his late mature work. This path also leads to his most challenging work because of the renewed and difficult colloquy between himself in the world and God in the world which he has established through the spiritual work of the poetry.

This new colloquy required faith, not mind to bridge the alienation between God and this world. In an important sense, Hopkins was fighting for his spiritual life in this year of the terrible sonnets, and the plane upon which this battle takes place is in the poetry, hence the deepened and intense feeling of loss and despair that emerges in some of the sonnets. Leslie Higgins and Noel Barber summarized his working tablature this way: in the contemplation of nature he found intense pleasure, in poetic composition his natural fulfillment, and in the religious and priestly life his ideals and values 4 (469).

Little wonder that such a deep shift in his aesthetic as a poet should result from seismic shifts in his personal and spiritual lives. To continue with the Emersonian reference for a moment longer, Hopkins likely recognized that his earlier poetry was more mirror than lens, and so from before to after 1885-6, we see octaves and sestets break into quatrains and tercets, suggesting a fragmentation within the poems(179 Higgins & Barber), and ultimately as in That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire,we encounter a greater willingness to transgress and reshape the form and language of poetry in order to more fully connect with God in nature, small n. What a poem like God's Grandeur'achieves in its use of nature is very like in imagery to the work of the Late Romantics, with the presence of God reflected ('shook foil') in the harsh nature of man's toil (seared,''bleared, smeared and smudged), but which is transcended in the second stanza by the work of the Holy Ghost moving through the largeness of Nature capital N (freshness deep down things) that is most manifest in the dawn, the Holy Ghosts's bright wings'over the landscape. This imagistic pattern reflects, for all its earnestness, nature held at a distance, and the greater the distance, the more tolerable are the muck and mire (ooze of oil Crush) of men's hard lives. If we consider one of the six sonnets in question, say Wake and Feel,the difference I am suggesting might become clearer. Gone is the outwardly transcendent Holy Ghost who connects man's smudge and . . .man's smell to the larger intelligence of God, and in its place we sense the inner darkness of a man struggling to reach his God and failing to find the language to do so:

I wake and feel the fell of dark, not day.

What hours, O what black hours we have spent

This night! what sights you, heart, saw; ways you went!

And more must, in yet longer light's delay.

With witness I speak this.

But where I say

Hours I mean years, mean life.

And my lament Is cries countless, cries like dead letters sent

To dearest him that lives alas! away.

I am gall, I am heartburn. God's most deep decree

Bitter would have me taste: my taste was me;

Bones built in me, flesh filled, blood brimmed the curse.

Selfyeast of spirit a dull dough sours. I see

The lost are like this, and their scourge to be

As I am mine, their sweating selves; but worse.

The poem reads like an x-ray of the mind's self, a searing exposure of the darkness that dwells there, almost as though the discovery that what previously presented itself as 'in-sight' was a mere reflection of the self, a stirring of the mind, not of the heart. The persona of this poem is indeed a Dark Mind. The dead lettersreferred to in the first stanza come from this mind, whose heavy anguish is powerfully felt, but which is finally recognized in the second stanza as not God's most deep decree, but rather the mind's construction my taste is me.

In a letter to Bridges dated September 1st 1885 which announces the arrival of the two poems I wake and feel the fell of dark and No worst, there is none, Hopkins complains that his mind is continually jaded and harassed, concluding finally that in this dark interregnum of his, he was thinking too much and doing too little 5 (263). There is no natural imagery here as there was in God's Grandeur, no delight in the formal poetic dance with the divine; that old lexicon is dead. Consider now the triumphant That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire,which begins by returning to the natural imagery that we associate with Hopkins' earlier poetry, like Binsey Poplars, God's Grandeur and Pied Beauty:

Cloud-puffball, torn tufts, tossed pillows | flaunt forth, then chevy on an air-built thoroughfare: heaven-roysterers, in gay-gangs | they throng; they glitter in marches.

Where the fretted lines in God's Grandeur have largely descriptive words and verbs/actions stacked up before the nouns which are usually the heaviest points in the line (Generations have trod, have trod, have trod and the brown brink eastward'), the stacked language in That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire is accretive, designed to layer nuances of meaning that lead to the break out final stanza. So, Squandering ooze to squeezed | dough, crust, dust; stanches, starches Squadroned masks and manmarks echoes later in the exultant response to the rhetorical question that signals this key break in the poem.

Thus, Is any of him at all so stark | But vastness blurs and time | beats level is answered by, Enough! the Resurrection, | a heart's-clarion! Away grief's gasping, | joyless days, dejection. The penultimate moment in the poem, then (I am all at once what Christ is . . .), is a new transcendence, the Resurrection made personal, the means to lift oneself past the deadening repetition of flesh and earth and self. Structurally, the poem deconstructs the sonnet form, something that other poems of the period would repeat (think of Spelt From Sibyl's Leaves), and in so doing allows through this reconstruction the colloquy that Hopkins had lost in the dark passage that produced the €˜terrible sonnets.So, back to the title of this talk, Dark Mind, Light Soul: what was the proximate cause of Hopkins' loss of spiritual and aesthetic footing? No Worst, There is None perhaps offers a major clue.

One of the terrible sonnets, this poem has often been cited as an example of the poet's spiritual nadir, his lowest moment both spiritually and emotionally.

There is another angle of approach, however, and it derives from a fellow writer that Hopkins was most certainly familiar with, Shakespeare, namely in the scene between Edgar and Gloucester in Act IV, scene 1 of King Lear. We all know the scene: Gloucester has been blinded by the cruel Regan and her consort Cornwall, and his legitimate son Edgar has led the old man to what he's convinced are the cliffs of Dover, ostensibly to commit suicide. Lear is distraught, despairing, and cut off from any succor that his God or his family might offer him. Edgar plays upon Lear's mind to convince him that a few paces ahead lies the edge of the cliff, waiting for him to break finally and permanently from the world and God.

Like the poet, it is Edgar who elucidates the depth of despair

engendered by his father's misfortune. This is an important point: Edgar

playing on Lear's mind's first look closely at Hopkins' poem:

No worst, there is none.

Pitched past pitch of grief,

More pangs will, schooled at forepangs, wilder wring.

Comforter, where, where is your comforting?

Mary, mother of us, where is your relief?

My cries heave, herds-long; huddle in a main, a chief

Woe, world-sorrow; on an age-old anvil wince and sing.Then lull, then leave off. Fury had shrieked ˜No ling-ering! Let me be fell: force I must be brief

O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall

Frightful, sheer, no-man-fathomed.

Hold them cheap

May who ne'er hung there.

Nor does long our small Durance deal with that steep or deep.

Here! creep,

Wretch, under a comfort serves in a whirlwind: all

Life death does end and each day dies with sleep.

Consider the second stanza, still directed within a conventional sonnet structure, especially at the language that describes the treachery of the mind, 'O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall | Frightful, sheer, no-man-fathomed. Hold them cheap | May who ne'er hung there.'

No man can understand the despair of stanza one who has not contemplated the 'cliffs of fall'designed by the mind; this is the lesson that Lear must learn before he can come back into his humanity, into his connection to God and his family. Now consider Edgar's words in Act IV as he contemplates his father's desparate and desolate desire to kill himself: O gods! Who ist can say, I am at the worst? I am worse than e'er I was . . . And worse I may be yet; the worst is not So long as we can say, This is the worst. (iv. 1)

Shortly after Edgar speaks these words in an aside to the audience, Lear sums up the moment between them by saying,

As flies to wanton boyes are we to the gods.

They kill us for their sport.

Dark Mind in this case refers to what the mind has hidden from the despairing Lear; cannot daub it further, concludes Edgar in his final aside of the scene, as he stands aside and

lets his father's despair drive to its inevitable conclusion.

In Hopkins' case, Dark Mind names what created the existential

chasm that he experienced in 1885-6. Light Soulin the title of this

talk speaks to the source of personal Resurrection that eventually

resolves Hopkins' spiritual and aesthetic crisis. Whereas Hopkins

presents No worst, there is none'to Robert Bridges using images of blood , I have after a long silence written two sonnets, which I am touching: if ever anything was written in blood, one of these was (Milward

147), the later poetry that he showed Bridges shortly before his death,

most especially To R.B., is more securely resolved spiritually and

aesthetically, something that affects both the soul and, ultimately,

the mind:

Sweet fire the sire of muse, my soul needs this; I want the one rapture of an inspiration. O then if in my lagging lines you miss The roll, the rise, the carol, the creation, My winter world, that scarcely breathes that bliss Now, yields you, with some sighs, our explanation.

In Hopkins' earlier poetry, the spiritual source for his theory of inscape is the power and epistemological clarity offered by the miracle of the Incarnation, wherein the divine mystery was made flesh and worldly, perceivable to the eye and heart of the poet . This point of origin fails in 1885 [speculate why?] until it is supplanted by the later and greater miracle of the Resurrection, a Christly miracle that parallels the poet's own rebirth as a post Romantic, perhaps as an early Modernist.

As Daniel A Harris noted, what Hopkins did not perhaps sufficiently realize [until 1885] was that insofar as the metaphysic depended upon his continued exercise of the penetrative imagination in discovering Christ within things, his Incarnationist theology was in thrall to his temperament'(35). After all, Christ's disappearance is the inescapeable theological and poetic foundation of the terrible sonnets (35). In this way, Hopkins' aesthetic followed his theological understanding and so a fundamental shift in the latter profoundly affected the former, something which is part of the lament in awake and feel. So, to conclude. I remember enough of my Jesuit high school education to recall how we were enjoined in our religion studies to feel the transformative power of Christ's miracles, to appreciate first how moments like the Resurrection had to do with me personally, before grappling intellectually with the meaning of resurrection as a theological construction. Flesh/heart first, then the mind follows to an understanding of the work required of Christ's followers in this world.

That this was prominent in Hopkins' working imagination during

1885

End Notes

1. It's worth pointing out, I think, especially because of Hopkins long career working several languages, including Greek, Latin and Anglo-Saxon, that the word €˜terrible' is related to the Latin and French meaning 'to shiver'both from fear and from awe.

2. This point would require, of course, that Hopkins reject the Nature imagery that had been part of the poetical lexicon of English poetry for nearly a century.

3. Robert J. Walker, Labyrinths of Deceit: Culture, Modernity and Identity in the Nineteenth Century. Liverpool, UK: Liverpool University Press, 2007.

4. Lesley Higgins and Noel Barber, ''If You Knew the World I Live In!': Hopkins and University College. Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review. Vol. 103. No. 412. (Winter 2014/15). pp. 462-472.

5. Gerard Manley Hopkins, The Major Works, including all the poems and selected prose. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2002.

6. is discernible in the different opening lines of some of the terrible sonnets, most of which are plaintive, focused on the pain felt by the persona which is caused by god's unresponsiveness. Think of 'My own heart let me more have pity on,'or 'Not, I'll not, carrion comfort,'or even 'No worst, there is none.'These poems open on a note of negation or of inadequacy, something very different from the powerful affirmations of earlier poems like 'The Windhover,''I caught this morning's minion, king- | dom of daylight's dauphin'or from 'God's Grandeur,''The world is charged with the grandeur of God.' That Hopkins could return from his time in this desert with a deeper and more personal sense of self anchored in God's presence in the world is a testament, really, to the abiding strength of his faith. As he says in 'That nature is a Heraclitean Fire,'written in 1888€”the year before his death, 'In a flash, at a trumpet crash, | I am all at once what Christ is, | since he was what I am, and | This Jack, joke, poor potsherd, | patch, matchwood, immortal diamond, | is immortal diamond.€

The poem begins in a landscape recently ravaged by a storm

(yestertempest's creases), an oblique bow to his longest and earliest

published poem The Wreck of the Deutschland,and ends

defiantly, on a note of what critic Brian Robinette has called

eschatological hope 14. True to the mutability inherent in his

choice of Heraclitean for the poem, despair gives way to hope,

darkness, a darkness of the mind gives way to the lightness of the soul.

Thank you.

Check out other Lectures by Robert Smart in the Hopkins Archive

Lecturers in GM Hopkins Archive

Subjects, Topics included in The Hopkins Archive

Hart Crane, An Influence

Gerard Manley Hopkins in Dublin

Hopkins Lectures 2017

Hopkins Lectures 2017Book Review:Hopeful Hopkins by Desmond Egan

Bridges Preface to Hopkins' Poems: William Adamson Univ. Ulm

Berryman John and GM Hopkins: Patrick Samway SJ

Neurosis and Art: Desmond Egan

Irish Exile and Terrible Sonnets : Robert Smart Quinnipiac