Hopkins and Robert Bridges Friendship

William Adamson,University of Ulm,

Germany .

This Lecture was delivered The Hopkins Literary Festival July 2013.

1. Prologue

Gerard Hopkins and Robert Bridges might be considered an odd couple, physically 1very unalike and divided by many psychological and religious differences, and not least by their approach to and understanding of poetry. But despite this, the friendship that began at Oxford University in 1863 was to last twenty-six years, right up until Hopkins’ death in 1889.

Hopkins’ relationship with Bridges is readily accessible to us, as the letters he wrote to him provide a detailed view of the nature of his friendship. Bridges’ relationship with Hopkins is less transparent: following Hopkins’ death, Bridges had all of his letters to him returned and destroyed, and although we can infer what the content of many might have been from the replies, the tone and the quality of the communications is denied us, with the result that many questions are irritatingly left unanswered.

Bridges would appear to have gone to great lengths to preserve his privacy. Some of the reasons may be found in his character: one fellow writer, Siegfried Sassoon, wrote after meeting him that he was “proud, self-conscious, and often aggressively intolerant. There was something " self-contradictory " about him” going on to refer to “petulant exhibitions of rudeness.”

Our interest in Bridges lies greatly in his role as literary executer of Hopkins’ poems, which he kept collectively from the public until 1918, twenty-nine years after his friend’s death, when he edited Poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins for publication.2

Was it simply the editorial challenge that daunted him? Other close friends had received more attention, Richard Dixon, Digby Dolben and Henry Bradley being recognised with individual memoirs, 3 published together as Three Friends in 1932. Why did Hopkins, surely the most important friend from a literary and poetic point of view, not merit at least a similar memoir? (4) And when the poems were eventually printed, Bridges attached a “Preface to Notes”, a critical introduction which leaves us wondering why he bothered at all; he writes:

Apart, from faults of taste, which few as they numerically are yet affect my liking and more repel my sympathy than do all the rude shocks of his purely artistic wantonness “ apart from these there are definite faults of style which a reader must have courage to face, and must in some measure condone before he can discover the great beautie5

“Courage to face”, “in some measure to condone”, “wantonness”: this would seem a strange endorsement, and the preface was in a way, as Elgin W. Mellown has remarked, “Bridges’ opportunity to state his objections to Hopkins’ verse and to voice his prejudices against his friend’s religion”.( 6) Yet despite these blunt comments, which only underline the polarity of each man’s understanding of poetry, Bridges was concerned with the recognition of his friend’s work and the reader’s discovery of those “great beauties”: we owe Bridges a great debt, and without him we would probably not have Hopkins.

2. Robert Bridges: the Man

Bridges was born on the 23rd October 1844, three months after Hopkins (28th July 1844). His father died when he was nine years old and he was sent to Eton College in 1854 before going up to Corpus Christi College, Oxford in 1863, where his acquaintance with Hopkins began.

Bridges “was a good but not top student”, (7) and received his degree, a second class in literae humaniores, or Classics, in 1867. The class was no surprise to Hopkins who wrote in a letter to his friend, “A 2nd is the class I have always imagined you wd. get: mind it is a good

one”8). Hopkins on the other hand, received a Double First. In 1869 Bridges registered as a student at St Bartholomew's Hospital, London. He failed his medical examinations in 1873, and then spent the July of the following year studying medicine in Dublin, beating Hopkins to Ireland by some ten years. He received his MB in December 1874. He then worked at St. Bartholomew's and other hospitals until 1881, when he retired from practice after a bout of pneumonia, and spent the rest of his life writing. In 1913 he was appointed Poet Laureate (a contentious choice at the time( 9), a post which he then held until his death in 1930.

3. Gerard Manley Hopkins and Robert Bridges: the Early Years

Hopkins and Bridges met first at university, Norman White supposes that it might have been ”at one of Canon Liddon’s Sunday evening lectures in the Michaelmas term of 1863 10,10 and their correspondence began in 1865. The early letters from Hopkins to Bridges indicate that a firm friendship had developed between the two men, exchanging invitations to stay and information on their daily lives and experiences and mutual friends. The intensity of the friendship, at least on Hopkins’ part, is evident. In 1867 he wrote: “With regard to the invitation very many thanks for your kindness. But I think I will, if you will let me, refuse it 'the very pleasure I had in my stay last year is part of the reason why I do not wish to make another'.” 11

It was during this stay with Bridges’ family in 1866, which Hopkins told his father had been “the happiest fortnight of my life” (Phillips: 1991, To Robert Bridges 16/10/1866), that he had been in the process of disengaging himself from the Anglican Church and converting to Roman Catholici12 a monumental event in his life which he had not thought he could share with Bridges, and it may well be that his feeling that he had been dishonest towards his friend led him to decline the subsequent invitation. Hopkins was received into the Roman Catholic Church in October 1866.

Bridges, Jean-Georges Ritz reminds us, had an “unconquerable repugnance to the full-blown Roman theology”, 13 and this was to be a watershed in their relationship. In 1866, apparently quoting Bridges’ letter to him, Hopkins wrote in reply: “You were surprised and sorry, you said, and possibly hurt that I wd. not tell you of my conversion” (Phillips: 1991, To Robert Bridges 22/11/1866). And in a second letter written six days later defends his actions further: “ it was from no natural reticence," but from the plain conviction of the unkindness and "treachery of letting you know.” (Phillips: 1991, To Robert Bridges 28/11/1866).

The repercussions for Bridges and Hopkins were immense, and their relationship lost much of the trust and intimacy that had existed up until this point. The issue of religion was to remain a deep division throughout their friendship, Bridges writing to Dixon in 1889 that Hopkins “seemed to have been entirely lost & destroyed by those Jesuits. 14

4. An Uneasy Friendship

The unique closeness and the confidence the two undergraduates had, was gone. For Hopkins came his novitiate with the Jesuits which was to last nine years before his eventual ordination at the age of 33 in 1877; for Bridges came the pursuit of a medical career which, however, was to last only three years. Thompson writes without irony that “To a man of such quick feelings we can imagine what a burden must have been the tedious and often distressing duties which he endured daily for so many years.15

As priest and physician respectively, the two men would certainly have been confronted with the deprivations of the working class. Hopkins as a priest in parishes in such places as Manchester and Liverpool, and Bridges in his work as a casualty doctor would have seen the results of the urban poverty and the harsh working conditions of the time. Both men shared the social and political prejudices of their class, however whereas Hopkins made every effort to understand the causes of the social problems of his day, I think it is fair to say that Bridges, who believed in an hierarchical class system rather than a levelling democracy, probably did not.

One of the main pieces of evidence for this is Hopkins’ famous “red letter”, written in the August of 1871, where he states: “Horrible to say, in a manner I am a Communist”. This statement, however, cannot stand alone, and the letter goes on to demonstrate how profoundly Hopkins was thinking about the plight the socially dispossessed:

But it is a dreadful thing for the greatest and most necessary part of a very rich nation to live a hard life without dignity, knowledge, comforts, delight, or hopes in the midst of plenty — which plenty they make. They profess that they do not care what they wreck and burn, the old civilisation and order must be destroyed. This is a dreadful look out but what has the old civilisation done for them?16

Catherine Phillips writes that "Bridges was more class conscious than Hopkins and would have been horrified at the idea of revolution.”17 And indeed this was a step too far, and the letter was treated with dismissal. Two and a half years later Hopkins writes:

My last letter to you was from Stonyhurst. It was not answered, so that perhaps it did not reach you. If it did I supposed then and do not know what else to suppose now that you were disgusted with the red opinions it expressed, being a conservative. So far as I know I said nothing that might not fairly be said. If this was your reason for not answering it seems to shew a greater keenness about politics than is common.18

In fact from 2nd August 1871 to 22nd January 1874 there was no further exchange of letters, and when the correspondence did begin again, Hopkins was not prepared to ignore the elephant in the room: “I think, my dear Bridges, to be so much offended about that red letter was excessive.”19 (Phillips: 1991, To Robert Bridges 22/1/1874).

5. Poets and Literary Men

The bulk of their correspondence was between 1877 and 1889 and for the most part their letters would appear to be centred on those interests they held in common: literature, poetry and music. There seemed to be little else that the two men could comfortably share, and religion was to remain a permanent bone of contention.

However, as late as 1874, Hopkins, it would appear, had seen nothing of Bridges’ poetry (“Did I ever before see anything of yours? I cannot remember, he writes in January 1874). Remember: this was after the period of estrangement when neither would have known much about the other’s activities, and indeed Bridges did not send Hopkins any of his poetry until 1877. From this point on, however, the two men regularly exchanged their work for comment and criticism.

Anne Treneer has written that Hopkins was “intensely receptive to the poetry of others”, and that his “best criticism " is in his private letters when he was freely following his natural bent.20 Indeed, Hopkins was a skilled and systematic critic, and his judgement of Bridges’ work shows an excellent eye for metre, rhythm, the concise and accurate use of language and coherency. He could be uncompromising and direct in his comments it is true, but the pill was always gilded. On a recently published volume of Bridges’ poetry he wrote in 1877: “In general I do not think you have reached finality in point of execution, words might be chosen with more point and propriety, images might be more brilliant etc.” but says too that “The sonnets are truly beautiful," and make me proud of you.” (Phillip: 1991, To Robert Bridges 3/4/1877).

Hopkins’ direct criticisms may not always have been agreeable to Bridges, and he often ignored them, but he appears to have craved his friend’s praise to a degree which almost suggests a lack of confidence in his own poetic ability. Hopkins had little time for such affectation:

You ask [he wrote in 1879] whether I really think there is any good in your going on writing poetry. The reason of this question I suppose to be that I seemed little satisfied with what you then sent and suggested many amendments in the sonnet on Hector. You seem to want to be told over again that you have genius and are a poet and your verses beautiful. You have been told so, not only by me but by others;. You want perhaps to be told more in particular. I am not the best to tell you, being biased by love, and yet I am too 21

His candour, his refusal to feed Bridges’ ego, and above all his motivation the love he has for his friend reveal a great deal about the man Hopkins was. The situation was different in the reverse. Hopkins probably sent his first poems to Bridges for comment in April 1877,22 and from this point on Bridges was his most trusted literary confidante and critic. It is probably fair to say that Bridges, certainly post 1881 when he regarded himself as a professional poet, would have considered Hopkins’ poetry as the “wild experiments of an amateur”, as Jean-Georges Ritz has put it. What we can say is that he had no real comprehension of Hopkins’ verse and his style, complaining more than once of unintelligibility. Hopkins’ replies were unrepentant: “Everybody cannot be expected to like my pieces. Moreover the oddness may make them repulsive at first.” Going on to say that:

My verse is less to be read than heard, as I have told you before; it is oratorical, that is the rhythm is so. I think if you will study what I have here said you will be much more pleased with it and may I say? converted to it. You ask may you call it ‘presumptious jugglery’. No, but only for this reason, that presumptious is not English. I cannot think of altering anything. Why shd. I? I do not write for the public. You are my public and I hope to convert you.23

Hopkins’s weary sigh is almost audible, and whereas it is beyond doubt that Hopkins was of considerable assistance to Bridges in his poetry, it is a moot point whether the opposite was the case.24

6. The Surviving Letter

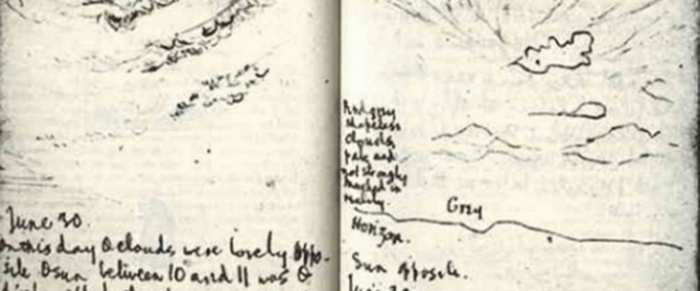

I mentioned at the beginning of my talk that Bridges had had all of his correspondence with Hopkins destroyed; this is not entirely true, one letter survives, written in May 1889:25

Dearest Gerard, I am so sorry to get a letter from one of your people telling me that you are ill with fever. And yesterday I sent you off a budget of notes on Milton's prosody. And when I last wrote I never mentioned your ailing tho’ you told me in your letter that you had interrupted it to lie down. What is this fever? F. Wheeler says that you are mending. I hope you are recovering properly; let me have a line I wish I cd. look in on you and see for myself. You must send me a card now and then, and one as soon as possible to let me know about you. Meanwhile I must be patient. I think that if you are really mending Miltonic prosody will be just the sort of light amusement for your mind “ I hope you are well enough already “ and will make a quick recovery and complete for wh. I pray. Yrs affc. R.B. 26

The letter is an interesting subject for analysis and tells us much about Bridges’ personality and his relationship to his friend. From the intimate superlative greeting and use of the first name, through the disjointed expression of sorrow to hear from “one of your people”, marking the religious gulf that existed between them, followed directly by literary concerns and then back to an expression of regret for not asking after him in his last letter. He appears to express a genuine concern in the second paragraph, but the “meanwhile I must be patient” is ambiguous: does it refer to waiting for news of Hopkins’ health, or for his comments on Milton’s prosody? The latter, quite possibly, as Miltonic prosody 27 is suggested as a fillip for the mind – what of the body? This followed by “well enough already” well enough for what? To return to his duties as literary correspondent? Ending with the hastily abbreviated: “Yrs affc. R.B. I will not comment further other than to say in Bridges’ favour that he does show genuine warmth and concern in his wishes for a speedy recovery. Tragically this was not to be. Gerard Hopkins died on the 8th June, just three weeks after receiving Bridges’ letter.

7. Hopkins Posthumous

Following Hopkins’s death, Bridges wrote to Father Thomas Wheeler who, as Robert Martin tells us, had been superintending his care, to request that his letters to Gerard be returned. This was done, Father Wheeler writing to Bridges that Hopkins had given instructions for all his poems, diaries and notebooks to be placed into the hands of either his family or Bridges himself. Thus Bridges became de facto the literary executer of Hopkins’ verse, and the fate of Gerard’s poems rested in the hands of a man who, although undoubtedly his closest friend, was arguably not best placed to undertake the task of editorship. Bridges felt that Hopkins’s poetry was not for public consumption, an opinion in which he was backed up by another correspondent of Hopkins, Coventry Patmore.28

As an already established poet and a Roman Catholic convert, we might assume that Patmore would have had more understanding and sympathy with the purpose of Hopkins’ poetry: far from it, in August 1889 he wrote to Bridges that I, as one of his friends, should protest against any attempt to share him with the public 29. Seeking Patmore’s opinion was an unfortunate choice, and it could justifiably be said that he had even less understanding and appreciation of Hopkins’ poetic achievement than Bridges himself.

There had been an attempt in Hopkins’ lifetime to have some shorter poems published in an anthology entitled Sonnets of Three Centuries, edited by Hall Caine, who to a great extent epitomised conservative Victorian attitudes towards poetic form. Caine rejected the five sonnets submitted, and Hopkins in a letter to Bridges quotes Caine’s reason: “the purpose of his book " is to ‘demonstrate the impossibility of improving upon the acknowledged structure whether as to rhyme scheme or measure’.” (Phillips: 1991, To Robert Bridges 27/4/1881). This conservative attitude towards poetry prevalent at the time cannot be underestimated. Lawrence Binyon makes the point well that if they had been published, Hopkins’ poems, if not wholly ignored would have been thought a deliberate outrage, and simply execrated.30

In fairness to Bridges, it was always his intention to print Hopkins’ poems, but his firm belief that he held the high moral ground on poetic etiquette led him to disapprove of (and even fear) what he termed Hopkins’ “eccentricities” indeed, as late as late as 1916 he was still talking of Hopkins’ “queernesses31. Despite this he did publish some of Hopkins’ poetry in A.H. Miles’ Poets and Poetry of the Century in 1893,32 a mere four years after his friend’s death. Norman White tells us that eight poems were printed, adding that “an editor today would have difficulty in making a better selection.” (33)

Bridges included a brief account of Hopkins’ life and an introduction to the poetry – and here lies the rub: Bridges’ first draft tells the reader that the poems “miss some of those first essentials of beauty, which are attainable by all poets alike”. Jean-Georges Ritz comments dryly: “Could a critic say anything worse?” 34) Canon Dixon objected to the fact that “the notice ended with such fault-finding”,35 and Bridges revised the text, the final version of which ended as follows:

Poems as far removed as his come to be from the ordinary simplicity of grammar and meter, had they no other drawback, could never be popular; "[…] for they have this plain fault, that, aiming at an unattainable perfection of language ", they not only sacrifice simplicity, but very often, among verses of the rarest beauty, show a neglect of those canons of taste, which seem common to all poetry.36

A critic certainly couldn’t say much worse.

Two years later, in 1895, four more Hopkins poems appeared in print, in an anthology edited by Canon Henry Beeching entitled Lyra sacra: a Book of Religious Verse.37 Interestingly, permission to print the poems came from Hopkins’ father, Manley Hopkins, leaving Bridges out of the loop. Beeching is worthy of our attention in that he appears to have shown a good appreciation and recognition of the importance of Hopkins’ poems: “It is to be hoped” he wrote in 1895, “that before long his genius may be recognized in a complete edition.38 Unfortunately the poems were in the hands of Bridges and not Beeching. Hopkins continued to appear sporadically in anthologies, for example in The Oxford Book of Victorian Verse (1917) and The Oxford Book of English Mystical Verse (1917, before Bridges finally published the first edition of his poetry in 1918.

Many critics who reviewed the book showed a better understanding of Hopkins than Bridges, finding the poems immediately of great significance, and next to their comments Bridges’ own notes to the poems appear shabby and philistine. One review (the reviewer is sadly unnamed) in the Times Literary Supplement of January 1919 illustrates this well:

The verse survives the great test of verse; it is best read aloud; then the very sense becomes clearer and anyone with an ear can hear that the method is not affectation but eagerness to find expression for the depths of the mind, for things hardly yet consciously thought or felt. Hopkins, he adds, “begins where most poets leave off, not out of affectation, but because he wished to go further.39

That Bridges was Hopkins’ closest and dearest friend is beyond dispute. However he was certainly not the right man to act as literary executor for his poetry. Binyon’s point may well be made that had Bridges published Hopkins twenty-five years earlier, Robert Bridges and Contemporary Poets, he might have condemned him to literary execration and denunciation. However, the fact that Bridges, when he did eventually publish the complete poems twenty-nine years after Hopkins’ death, still so little understood what his friend’s work was about, and still felt the need to voice his prejudices, shows how little he understood of the development of poetry and its reception, and how little he, Bridges, had progressed where Gerard wished to go further.

Notes

- Hopkins was slight of stature, only five foot two inches in height, whereas, as Catherine Phillips tells us, Bridges was “over six feet tall” and “a considerable athlete”. Catherine Phillips, Robert Bridges, A Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992) p. 13.

- Published in London by Humphrey Milford. Bridges had published individual poems in anthologies prior to 1918.

- 1909, 1911 and 1926 respectively. Dolben’s memoir is today only of interest in as far as it throws light on the relationship between Hopkins and Bridges.

- Hopkins is, however, mentioned tangentially in the memoirs of Dolben and Dixon, and George Gordon tells us that a memoir was in fact planned immediately after Hopkins death. Cf. G.S. Gordon, Robert Bridges (Rede Lecture, 1931, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1946), p. 182.

- Robert Bridges (ed.) Editor’s Preface to Notes, Gerard Manley Hopkins Poems (1918), http://www.bartleby. com/122/101.html accessed 23.06.2013.

- Elgin W. Mellown, “The reception of Gerard Manley Hopkins’ Poems, 1918-1930” in: Modern Philology, Vol. 63, No. 1 (August, 1965) p. 38.

- Catherine Phillips, “Bridges, Robert Seymour (1844 1930), poet”, in: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press ©2004-2013) http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/printable/32066 accessed 23.06.2013.

- Catherine Phillips (ed.), Gerard Manley Hopkins: Selected Letters (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991), To Robert Bridges 12 November 1867.

- Prior to his appointment Bridges was not a well-known poet, and little of his work appealed to the public mind. It was for this reason that the connection of his name with the position of Poet Laureate, following the death of Alfred Austin, was not as popular with the public as those of Rudyard Kipling and others who had been mentioned as possibilities for the post.

- Norman White, Hopkins: a Literary Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992) p. 107. Hopkins had won a scholarship to Balliol College in 1862 and went to Oxford in the Easter term of 1863; Bridges went up to Corpus Christi on the Michaelmas term of the same year.

- Catherine Phillips (ed.), Gerard Manley Hopkins: Selected Letters (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991), To Robert Bridges 12 November 1867.

- He was in contact with John Henry Newman, writing to him that he was “anxious to become a Catholic, and I thought that you might possibly be able to see me for a short time when I pass through Birmingham in a few days, I believe on Friday” – on his way to visit Bridges in 1866. Cf. Phillips (ed.) op. cit. To Robert Bridges 28 August 1866.

- Jean-Georges Ritz, Robert Bridges and Gerard Hopkins 1863.1889: A Literary Friendship (London: Oxford University Press, 1960) pp. 11-12.

- Bridges to Dixon 14 June 1889, Bridges Papers, no. 87/1; quoted in: Phillips, Robert Bridges, p. 143.

- Edward Thompson, Robert Bridges, 1844-1930 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1944) pp. 7-8.

- Phillips (ed.), GMH Selected Letters, To Robert Bridges 2 August 1871.

- Catherine Phillips, Robert Bridges: A Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), p. 58.

- Phillips (ed.), GMH Selected Letters, To Robert Bridges 22 August 1874.

- Typically it was Hopkins who took the first steps towards reconciliation.

- Anne Treneer, “The criticism of Gerard Manley Hopkins” in: John Lehmann (ed.), The Penguin New Writing No. 40 (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1950) p. 102.

- . Phillips (ed.), GMH Selected Letters, To Robert Bridges 22 October 1879.

- “I composed two sonnets with rhythmical experiments of the sort, which I think I will presently enclose”, cf. Catherine Phillips (ed.), GMH Selected Letters, To Robert Bridges 2 April 1877.

- Phillips (ed.), GMH Selected Letters, To Robert Bridges 21 August 1877.

- We might be forgiven for wondering why, with so little understanding of Hopkins’ poetic vision, Bridges kept any of his poetry at all.

- Ritz suggests it is the only letter to have survived: cf. Ritz op. cit., p. 68.

- Bridges to Hopkins, 18 May, 1889, quoted in: Phillips, Robert Bridges: A Biography, p. 142.

- Miltonic prosody was something of an obsession with Bridges, and it was in 1889 that his work Milton's Prosody, with a chapter on Accentual Verse and Notes was published by Oxford University Press.

- Hopkins corresponded with Patmore for five years, between 1883-1888, and sent him many of his poems.

- Coventry Patmore to Robert Bridges, 12 August 1889, quoted in: Jean-Georges Ritz, op. cit., p. 158.

- Lawrence Binyon, “Gerard Manley Hopkins and His Influence”, in: the University of Toronto Quarterly, VII (1939 – 39) p. 265.

- Donald E. Stanford (ed.) The Selected Letters of Robert Bridges, Volume 2 (Cranberry NJ: Associated University Presses, 1984), 749: To Mrs Manley Hopkins, 17 January 1916.

- A. Miles (ed.), The Poets and Poems of the Century, vol. 8: Robert Bridges and Contemporary Poets, London, 1894.

- The poems chosen by Bridges were: “parts of ‘A Vision of the Mermaids’ and, complete, ‘The Habit of Perfection’, ‘The Starlight Night’, ‘Spring’, ‘The Candle Indoors’, ‘Spring and Fall’, ‘Inversnaid’, and ‘To.R.B.’” Norman White, op. cit., p. 461.

- Jean-Georges Ritz, op. cit. p. 160.

- Quoted in Norman White, op. cit., p. 461.

- Robert Bridges, Preface to A. Miles (ed.), The Poets and Poems of the Century, Vol. 8, London, 1894.

- Henry Charles Beeching (ed.), Lyra sacra: a Book of Religious Verse (London: Methuen, 1895). Poems by Bridges and Dolben also appear in this anthology.

- Henry Charles Beeching (ed.), A Book of Christmas Verse (London, 1895), p. 173.

- Review of Gerard Manley Hopkins, Poems (1918) In: Times Literary Supplement, January 9, 1919, p. 19. (Unnamed reviewer).

Bibliography

- Beeching, Charles Henry (ed.), Lyra sacra: A Book of Religious Verse (London: Methuen, 1895). >Beeching, Charles Henry (ed.), A Book of Christmas Verse (London, 1895). >Binyon, Lawrence, “Gerard Manley Hopkins and His Influence”, in: the University of Toronto Quarterly, VII (1939-39).

- Bridges, Robert (ed.), Editor’s Preface to Notes, Gerard Manley Hopkins Poems (1918).

- Bridges, Robert, Three Friends (London: Oxford University Press 1938). Gordon, G.S.,

- Robert Bridges (Rede Lecture, 1931, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1946).

- Horace, “On The Art of Poetry” (Epistle to the Pisos), http://www.ourcivilisation.com/ smartboard/shop/horace/ arspoet.htm

- Mackenzie, Norman H., A Reader’s Guide to Gerard Manley Hopkins Thames and Hudson.

- Mellown, Elgin W., “The Reception of Gerard Manley Hopkins’ Poems, 1918-1930” in: Modern Philology, Vol. 63, No. 1 (August, 1965).

- Phillips, Catherine (ed.), Gerard Manley Hopkins: Selected Letters (London: Oxford University Press, 1991).

- Phillips, Catherine, Robert Bridges: A Biography (Oxford: OUP, 1992).

- Phillips Catherine, “Bridges, Robert Seymour (1844â “1930)”, in: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press ©2004-2013) http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/printable/32066

- Ritz, Jean-Georges, Robert Bridges and Gerard Hopkins 1863-1889: A Literary Friendship (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1960).

- Sassoon, Siegfried, Siegfried’s Journey, 1916-1920, (London: Faber & Faber, 1945). Stanford,

- Donald E., Robert Bridges Selected Poems (Cheadle: Carcanet Press, 1974). Standford, Donald E. (ed.), The Selected Letters of Robert Bridges, Volume 2 (Cranberry NJ: Associated University Presses, 1984).

- Thompson, Edward, Robert Bridges 1844-1930 (Oxford: Oxford University Press 1944). Times Literary Supplement, January 9, 1919.

- Treneer, Anne, “The Criticism of Gerard Manley Hopkins” in: John Lehmann (ed.), The Penguin New Writing No. 40 (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1950).

- >White, Norman, Hopkins: A Literary Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992).

Adamson William, University of Ulm, Germany contributed Other Lectures to the Hopkins Literary Festival

- Gerard Hopkins and Robert Bridges

- Gerard Manley Hopkins and Louis MacNeice

- The Man from Petrograd 1918

- A Close Reading of God's Grandeur

- Hopkins and Bridges - an Unusual Friendship (2022)

Lectures from 2013 Hopkins Festival