Vision and perception in Gerard Manley Hopkins’s ‘The peacock’s eye’

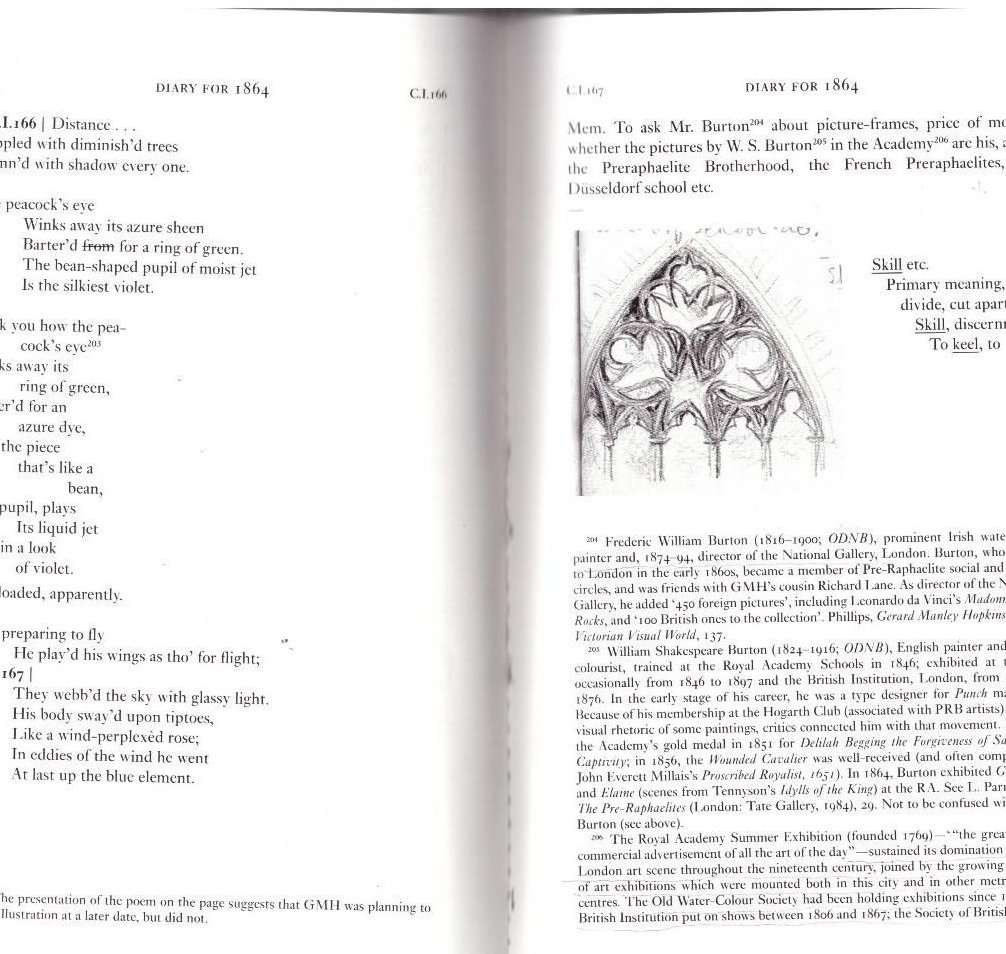

Katarzyna StefanowiczGerard Manley Hopkins’s diary from his early Oxford years are a medley of poems, fragments of poems or prose texts but also sketches of natural phenomena or architectural (mostly gothic) features.

In a letter to

written around the time of composition of the short lyric ‘The peacock’s eye’ (22 July, 1864) Hopkins wrote, ‘I have now the more rational hope than before of doing something – in poetry and painting.’ Alexander Baillie

The ‘and’ conjunction suggests that he was not going to pursue one of his interest at the expense of the other. Rather, he was planning to follow in the footsteps of the members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

who had been known for writing poetry alongside painting pictures, with some of their poems being verbal commentaries to the individual paintings. From what Hopkins wrote in his diary at that time it becomes clear that his interests revolved around modern medievalism and the Pre-Raphaelites. On 18 July he mentioned ‘Dixon. The Brownings, Miss Rossetti. D.G. Rossetti.’ Then he followed up with a list of the Pre-Raphaelites, providing names of the ones whom he probably deemed worthy of praise and admiration. ‘The Preraphaelite brotherhood. Consisting of D. G. R., Millais, Holman Hunt, Woolner and three others. One of these three went out to Australia.’ We can see that at that point he was not well informed about the Pre-Raphaelites, because it was Woolner who went to Australia.

Hopkins's Distinctive Visual Perception Influenced by Early Contact with the Pre-Raphaelites

Hopkins's visual perception may have been influenced by his early contact with the Pre-Raphaelites and the writings of John Ruskin

as their mentor as well as an astute observer himself.

Hopkins frequented different art exhibitions. When he wrote ‘The peacock’s eye’ he had just been to three London exhibitions: New Water Colour Society, Old Masters at The British Institution, and the Royal Academy Exhibition of summer 1864. The latter included pictures by the Pre-Raphaelite painters: John Everett Millais, Arthur Hughes, Frederic Sandys. One of the paintings by Arthur Hughes, called )Silver and Gold, might have fforded some inspiration for Hopkins’s ‘The peacock’s eye’.

The most famous magazine on art in the second half of the nineteenth century, praised Hughes’s paintings as being ‘each and all poetic and refined in conception, and singularly sensitive to delicate and harmonious modulations of colour.’ Hopkins did not comment on Hughes’s painting, yet it is tempting to imagine that he highly admired the meticulous way the peacock was depicted, and wanted to apply the Pre-Raphaelite ideas to a verbal description of the bird’s open train himself.

‘The peacock’s eye’ show Hopkins’s Visual Perception at Work

'The peacock’s eye', examined on its own, and then together with the other two poems show Hopkins’s visual perception at work. There is a visual process going on during which Hopkins changes his mind and adjusts what he writes to the way he sees. The MSS copy of page 166 shows that while writing the first version of the poem Hopkins did not think about adding a drawing or a sketch whereas the second version is jotted in a way which allows for some visual addition. Was he going to draw a peacock’s eye or something else? But how would he be able to capture in pencil the protean colour of the pattern which is the main theme of the poem?

One could argue that Hopkins didn’t want to destroy a sketch of a bird and a tree which is on the verso yet the sketch covers almost the whole previous page so the first version could possibly spoil it as well.

For my analysis of all the poems I use a scan of the spread (pages 166 and 167 in the MSS) from the modern scholarly edition of Hopkins’s Diaries, edited by Lesley Higgins. The first version of the poem, a quintain rhyming A BB CC, starts with the definite article ‘the’ moved sideways to the left to call attention to the uniqueness of a one particular organ of sight.

But is Hopkins talking about an eyeball? By using ‘winks’, ‘pupil’ and moist’ he complicates things as these words are suggestive of a sight organ. One feature which does not match a peacock’s eye is the bean-shaped pupil as birds’ pupils are round.

What Hopkins is talking about is the ‘oculus’ pattern on a peacock’s tail feather. The feather might be held in hand or it might be an integral part of the bird’s plumage. The lines of the poem flow in waves with two metrical patterns, iambic and trochaic, alternating, thus imitating slight movements of the feather due to which colours change. The two last lines are an extended metaphor. The word ‘violet’ stands not only for a colour but is a name of a beautiful, delicate flower, or a female name.

The revised version is a sestet rhyming AB AB CC. The meter is more ordered. Four trochaic lines change to iambic ones at the point when the key word ‘bean’ appears’. Again, this is the moment a reader realizes the poem does not refer to a bird’s eyeball. The verb ‘mark’ may have different meanings. The Oxford English Dictionary

gives dozens of them: to distinguish, to observe, to celebrate, to characterise, to indicate, to note, to portray, to reflect on, to consider. By choosing such a ‘rich’ verb, Hopkins leaves it to the spectator what role to play, and which mental faculties to employ. While comparing the two versions we can notice that from stating a fact in the first version Hopkins moves, in the second version, to forming an invitation. In this short dramatic monologue Hopkins invites an unknown audience to share the experience yet he introduces some hesitation about the accuracy of what might be seen. The ‘M

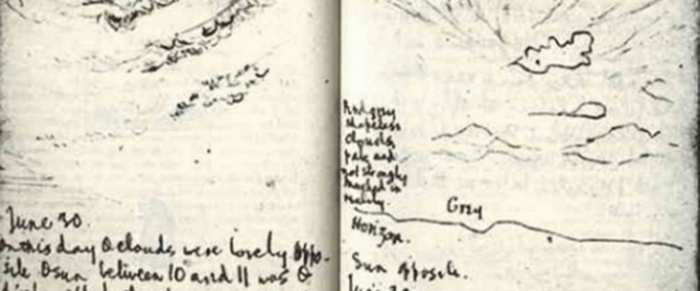

‘Distance / Dappled with diminsh’d trees’, is an unrhymed triplet which calls our attention to things seen from afar. In the MSS version Hopkins finishes the first line with one dot as though to mark the distance which becomes dappled with trees. These trees look like spots or dots joined by semi-darkness. The last poem ‘Love preparing to fly’, a septet rhyming ABB CC DD, might be a vision of Cupid and Psyche with Cupid being imagined as a butterfly or a moth. It is possible to see the webbed or veined wings of an insect while standing very close to one, preferably with a magnifying glass in one’s hand.>

It is worth noting that Hopkins might have got the idea of writing a poem about human visual perception at work from Ruskin.

Unlike )Modern Painters, which we can be absolutely sure Hopkins read, we can infer from how he formulated his ideas about the Romanesque architecture (December, 1863) that he read ) The Stones of Venice

as well. In chapter XXI, called ‘Treat of Ornament’ Ruskin wrote about Byzantine sculptors and the way they used to carve peacocks. He included his own drawing of a peacock in relief:

But the whole spirit and power of [the] peacock is in those eyes of the tail. It is true, the argus pheasant, and one or two more birds, have something like them, but nothing for a moment comparable to them in brilliancy: express the gleaming of the blue eyes through the plumage, and you have nearly all you want of peacock, but without this, nothing; (…) you must cut the eyes in relief, somehow or another; see how it is done in the peacock opposite: it is so done by nearly all the Byzantine sculptors: this particular peacock is meant to be seen at some distance. […] For every distance from the eye there is a peculiar kind of beauty, or a different system of lines of form; the sight of that beauty is reserved for that distance, and for that alone. If you approach nearer, that kind of beauty is lost, and another succeeds, to be disorganised and reduced to strange and incomprehensible means and appliances in its turn.

If we approach trees too near we don’t see them standing in a unique cluster any more, or if we look at a peacock from a far distance we will see a blue upper part of its body against a dark, brownish backdrop with colours being blurred, and if we do not approach a moth close enough we will never see the beautiful veins in its transparent wings. In these three poems Hopkins shows visual perception as a process undergoing changes in a short time due to the work of different factors such as light, distance or the receptiveness of the observer. Yet there is another, long-term process going on, one connected with Hopkins’s ever-growing life experiences and maturing.

On 17 May 1871 – some seven years later, Hopkins wrote a diary entry describing the peacock’s train in minute details. It was his subsequent encounter with the bird:

I have several times seen the peacock with train spread lately. […] The eyes, which lie alternately when the train is shut, like scales or gadroons, fall into irregular rows when it is opened, and then it thins and darkens against the light, it loses the moistness and satin it has when in the pack […]. He shivers it when he first rears it and then again at intervals and when this happens the rest blurs and the eyes start forward. I have thought it looks like a tray or green basket or fresh-cut willow hurdle set all over with Paradise fruits cut through – first through a beard of golden fibre and then through wet flesh greener than greengages or purpler than grapes – or say that the knife had caught a tatter or flag of the skin and laid it flat across the flesh – and then within all a sluggish corner drop of black or purple oil.

Hopkins embraces the bird’s beauty with his senses. The inscape of the bird is caught by sight, the imagery of juicy fruit like Paradise fruits, greengages and grapes, appeals to taste and smell, and the figure of a knife cutting the wet flesh invokes touch. In order to describe all those sensations Hopkins engages in a laborious search for proper words as if being constantly dissatisfied with images which come to his mind. He compares the peacock’s train to a tray, then to a basket, and finally to a fresh-cut willow hurdle. He talks about a fruit being cut to display its inner flesh but then deepens the sensation by talking about a ‘tatter or flag of a skin laid […] flat across the flesh’, as if searching for intensity, the unique essence of a thing. The ‘sluggish corner drop of black or purple oil’ may suggest some final decorative procedures taken during food preparation or, what is more probable, it symbolizes the anointing oil used for healing wounds, here inflicted with the knife.

In a letter to Baillie (July, 1863) Hopkins wrote, ‘I have particular periods of admiration for particular things in Nature; for a certain time I am astonished at the beauty of a tree, shape, effect etc, then when the passion, so to speak, has subsided, it is consigned to my treasury of explored beauty’. In my paper I tried to show how a small pattern on a peacock’s feather became a part of this treasury of beauty, explored by Hopkins thanks to his idiosyncratic way of looking at things, his unique mode of visual perception.

I would like to finish with this beautiful picture of a peacock’s tail feather drawn by Ruskin in 1877. It is portrayed with scientific precision, and amazing fastidiousness. When we compare the drawing with Hopkins’s description of the peacock’s feather we can see a lot of similarities, especially in colour and the oculus pattern. What Hopkins once said about ‘the great richness of the membering of the green in the elms, never however to be expressed but by drawing after study’ (August, 1867) does not seem to apply to his peacock’s eye description. The picture he painted with words equals in its detailedness, and beauty the watercolour by Ruskin.

Works Cited

- Hopkins, Gerard Manley, The Collected Works of Gerard Manley Hopkins. Correspondence, Vol.I, ed. by R.K.R. Thornton and Catherine Phillips (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

- Hopkins, Gerard Manley, The Collected Works of Gerard Manley Hopkins. Diaries, Journals and Notebooks, ed. by Lesley Higgins (Oxford; Oxford University Press, 2015). pp. 194-195.

- https://archive.org/details/earlypoeticmanus0000hopk/page/112/mode/2up

- Hughes, Arthur, Silver and Gold

- Ruskin John, The Art Institute of Chicago

- Ruskin, John, The Complete Work of John Ruskin

- The Art Journal of 1864

Lectures from GM HOPKINS FESTIVAL 2023

- Vision and perception in GM Hopkins’s ‘The peacock’s eye’ Katarzyna Stefanowicz

- Hopkins Trees and Birds Margaret Ellsberg

- Joyce, Newman and Hopkins : Desmond Egan

- Joyce's friend, Jacques Mercanton has recorded that he regarded Newman as ‘the greatest of English prose writers

’. Mercanton adds that Joyce spoke excitedly about an article that had just appeared in The Irish Times and had to do with the University of Dublin, “sanctified’ by Cardinal Newman, Gerard Manley Hopkins and himself.

Read more ...

- Hopkins and Death Eamon Kiernan

Gerard Manley Hopkins’s diary entries from his early Oxford years are a medley of poems, fragments of poems or prose texts but also sketches of natural phenomena or architectural (mostly gothic) features. In a letter to Alexander Baillie written around the time of composition He was planning to follow in the footsteps of the members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood who had been known for writing poetry alongside painting pictures ... Read more

Margaret Ellsberg discusses Hopkins's connection with trees and birds, and how in everything he wrote, he associates wild things with a state of rejuvenation. In a letter to Robert Bridges in 1881 about his poem “Inversnaid,” he says “there’s something, if I could only seize it, on the decline of wild nature.” It turns out that Hopkins himself--eye-witness accounts to the contrary notwithstanding--was rather wild. Read more

-An abiding fascination with death can be identified in the writings of Gerard Manley Hopkins. Easily taken for a sign of pathological morbidity, the poet's interest in death can also be read more positively as indicating, his strong awareness of a fundamental human challenge and his deployment of his intellectual and artistic gifts to try to meet it. Hopkins's understanding of death is apocalyptic. ... As will be shown, apocalyptic thought reaches beyond temporal finality. Hopkins's apocalyptic view of death shows itself with perhaps the greatest consequence in those few works which make the actual event of death a primary concern and which, moreover, leave in place the ordinariness of dying, as opposed to portrayals of the exceptional deaths of saints and martyrs. Read more

Lectures from Hopkins Literary Festival July 2022

- Landscape in Hopkins and Egan Poetry Giuseppe Serpillo

- Walt Whitman and Hopkins Poetry Desmond Egan

- Emily Dickenson and Hopkins Poetry Brett Millier

- Dualism in Hopkins Brendan Staunton SJ

Hopkins's Manuscript Notebook

Lectures delivered at the Hopkins Literary Festival since 1987

© 2024 A Not for Profit Limited Company reg. no. 268039