John Berryman’s High Regard for Hopkins

John Berryman, felt the pull and tug of an international group of poets. Yet, according to Paul Mariani,

one of his biographers, three poets were most influential in his writing career: Shakespeare, Yeats, and

Hopkins 1.

Patrick Samway, S.J.

Professor Emeritus of English,

Saint Joseph's University,

Philadelphia, USA

US Poet, John Berryman, visited Dublin 1966-67 (funded by The Guggenheim Fellowship)

The United States has profited enormously from the presence of Irish poets residing on its shores. One might think of Thomas Kinsella, born in the Inchicore area due west of Dublin, who after some studies at University College Dublin entered the Irish civil service, later to become writer in residence at Southern Illinois University and in 1970 professor of English at Temple University. Or perhaps Eavan Boland, a native of Dublin and a graduate of Trinity College, who is currently a professor of English and Director of the Creative Writing Program at Stanford University. If one were to include poets from Northern Ireland, then certainly Paul Muldoon, born on a farm in County Armagh, should be included. At Princeton University, he is both the Howard G. B. Clark Professor in the Humanities and Founding Chair of the Lewis Center for the Arts. And, of course, one must include the late Seamus Heaney from County Londonderry. A Nobel Prize winner, Heaney was professor of English at Harvard from 1981 to 1997, and its poet in residence from 1988 to 2006.

Let’s reverse directions. One highly celebrated American poet, John Berryman, felt the pull and tug of an international group of poets, some expatriates, including A. E. Housman, Dylan Thomas, Ezra Pound, W. H. Auden, and in his later years, T. S. Eliot. Yet, according to Paul Mariani, one of his biographers, three poets were most influential in his writing career: Shakespeare, Yeats, and Hopkins 1.

Having taught at Harvard, Princeton, Brown, and the Writers’ Workshop at the University of Iowa, as well as being an eminent professor of English at the University of Minnesota from 1955 until his death in 1972, Berryman is especially known for his long poem, Homage to Mistress Bradstreet (1956), as well as 77 Dream Songs (1964), which received a Pulitzer Prize, and His Toy, His Dream, His Rest, (1968), which received a National Book Award and a Bollingen Prize. The latter two texts were combined into a volume entitled The Dream Songs(1969), an intensely personal sequence of 385 poems. Before graduating from Columbia College in 1936, The Columbia Review (May-June 1936) contained a review by Berryman’s of Yeats’s plays and a bibliography of film criticism by his classmate Robert Giroux, who would become Berryman’s editor (and parenthetically editor of two of my books). Giroux played an important role in Berryman’s publishing career, especially in encouraging Berryman to write the best poetry he could, particularly during moments of depression and acute alcoholism. After having received the Kellett scholarship, which Giroux turned down, Berryman set out for two years of study at Clare College, Cambridge. In reply to what might be called a fan letter from Berryman, Yeats wrote to him from Rathfarnham, Dublin on November 9, 1936. Berryman informed his mother two days later :

I read him [Yeats] constantly and have dozens of the poems by heart, which is good because I needn’t have a book to be able to say them anywhere, on the bicycle or in bed.

On February 11, 1937, Berryman gave a talk on Yeats at the Dilettante Society, a literary group of Clare College, a prelude to meeting this poet on April 16th at the Athenaeum in London3 . So taken with Yeats, Berryman once even considered writing a biographical study of him. Later, one of his projects— a book of elegies, essays, and interpretations of the poetry of Yeats—was turned down by Macmillan Publishers. Gradually, Berryman began to study Hopkins more seriously, as had Thomas Merton, the future Trappist monk who entered Columbia as a sophomore in January 1935 and once envisioned writing a doctoral dissertation on Hopkins. While teaching at Wayne University in Detroit, Berryman came to know another faculty member, Bhain Campbell, whose wife Florence had been reading in 1943 John Pick’s Gerard Manley Hopkins: Priest and Poet, a book that attracted Berryman attention: “Hopkins,” according to Mariani,

had come to stand for Berryman as the model of the poet as artist and as a human being. What he himself had especially noted in reading Hopkins were the contrarieties, the particular mixture of ‘vigour & fatique, confidence & despair, the elegant & the blunt, the bright & the dry.’

What Berryman did not say was that he was now trying to get those same complex levels of diction into his own poems” (emphasis mine)4.Robert Bridges 5.

About this time, too, Berryman’s style underwent a metamorphosis. Yeats gave way to Rilke, and Rilke to Hopkins. Robert Lowell said of Berryman when they first met in 1944 at Princeton: "John had fire then, but not the fire of Byron or Yevtushenko. He clung so keenly to Hopkins, Yeats, and Auden that their shadows paled him.” 6.

Berryman’s first major poem, Homage to Mistress Bradstreet, which he had been working on since 1948, began to come together in June 1952 while teaching at Princeton; he had by then about 80 pages of notes and about 125 draft lines, employing an eight-line form similar to the 35 eight-line stanzas of Hopkins’s The Wreck of the Deutschland. “As with the Bradstreet poem,” he once told an interviewer, “I invented the stanza—it's a very beautiful, sort of hovering, eight-line stanza, unrhymed—and wrote the first stanza and stuck.” Berryman backed away from acknowledging that The Wreck of the Deutschland was part of the literary ancestry of his poem since he had only read the first stanza of The Wreck of the Deutschland, which he called “wonderful.”(8) Yet as John Haffenden has pointed out, there are verbal coincidences between these two poets, since Hopkins’s words “lull,” “flee,” and “sheer,” which appear in “Carrion Comfort” and “No worst, there is none” likewise appear in stanzas 30 and 31 of Homage to Mistress Bradstreet (9). There is more telling evidence to link these two poets. Compare, for example, the strained tone and imagery of stanza 2 in The Wreck of the Deutschland and the anguished portrayal of Anne Bradstreet in stanza 44, as she is now beyond the “shoal,” an important word used twice in Hopkins’s poem:

Thou heardst me truer than tongue confess

Thy terror, O Christ, O God;

Thou knowest the walls, altar and hour and night:

The swoon of a heart that the sweep and the hurl of thee trod

Hard down with a horror of height:

And the midriff astrain with leaning of, laced with fire of stress.

Bone of moaning: sung Where he has gone

a thousand summers by truth-hallowed souls;

be still. Agh, he is gone!

Where? I know. Beyond the shoal.

Still-all a Christian daughter grinds her teeth a little. This our land has ghosted with

our dead: I am at home.

Finish, Lord, in me this work thou hast begun.

Furthermore, the Bradstreet poem can be considered prologue to Berryman’s incredible Dream Songs, in which, as a poetic cartographer, he tried to explore his personal mindscape and landscape. In these poems, Berryman did not hesitate to manipulate syntax, formulate endless layers of impenetrable allusions, tossed off here and there with macho swag, and concoct bizarre subterfuges, all the while keenly aware that his own ordinary speech patterns would never reveal the freshness and originality of the intended idea. As critic Gerry Murray has written, “Throughout his career, Berryman displayed interest in abrupt syntactic shifts, lessons one can safely presume were taken from Hopkins.” Furthermore, another critic, Carol Frost, notes that the basis for the meters in both the stanzas of Hopkins and Berryman is accentual: “In Hopkins it is quite strict, according to his own lights [that is, as evidenced in his use of sprung rhythm]; in Berryman, loose but still present.” Like Hopkins, who sees similarity in what might strike another person as dissimilarity, Berryman relies on completely unexpected outward disassociations.” On the other hand, the cycle of these the Dream Songs differ from Hopkins’s deliberately structured poems; though developed thematically, each Dream Song, composed of three six-line stanzas, has a somewhat unpredictable rhythm and, at times, a herky-jerky quality. April Bernard, in her introduction to Berryman’s sonnets, makes a significant remark that could apply to Berryman’s Dream Songs:

“Since Wyatt, only Gerard Manley Hopkins and Berryman have been able to carry

off a comparable sustained dis-ordering of syntax to successful effect.”

W. S. Merwin, a former U.S. Poet Laureate and Pulitzer Prize winner who was one of Berryman’s students, stresses the importance of Hopkins for Berryman; [Berryman] “knew many of Hopkins’s poems by heart, and would quote phrases and passages, emphasizing the word order and the way the accented syllables had been set in the verse like notations in music. He was using lines of Hopkins as touchstones long before he had conceived of the Dream Songs.”

In looking at the control and fearlessness of both Hopkins and Berryman, it is good to appreciate

“the link that exists between rhythm and emotion: the real triumph is their ability to establish a baseline rhythm, strain against that rhythm for emotional nuance, and reestablish a new rhythm as immediately and often as the most passionate of emotions can ricochet.”

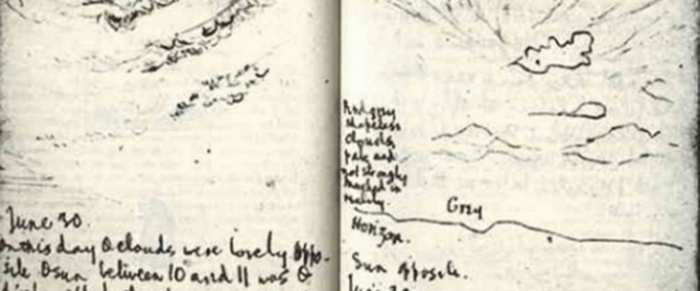

Once he had been recognized as an original, talented poet, Berryman spent the year, 1966-1967, in Ireland on a Guggenheim Fellowship. His goal was to write a second and concluding volume of The Dream Songs, which, just before he sailed with his wife Kate from Montreal on August 26th already numbered 259 such songs. While staying temporarily at the Majestic Hotel on Lower Baggot Street, Berryman gave a reading of his poem on Yeats at the Lantern Theatre. As he states in Dream Song 312, his trip to Ireland was really to try to surpass Yeats on his home turf:

“I have moved to Dublin to have it out with you /

majestic Shade. You whom I read so well

so many years ago….”

After moving to Lansdowne Park in the Ballsbridge section of Dublin, Berryman had great difficulty confronting this authoritarian ghost from the past, as he continued drinking, sometimes heavily, which caused depression and feelings of insecurity. At the end of January 1967, he was admitted to Saint Brendan's Hospital, a psychiatric facility located in the north Dublin suburb of Grangegorman. One highly significant poem, Berryman’s Dream Song # 377, provides a special insight into Hopkins, as seen through Henry, Berryman’s literary persona:

Father Hopkins, teaching Elementary Greek

whilst his mind climbed the clouds, also died here.

O faith in all he lost.

Swift went mad through his rooms & could not speak.

A milkman sane died, the one one, I fear.

His name is almost gone.

Hopkins’s credits, while the Holy Ghost

rooted for Hopkins, hit the Milky Way.

This is a ghost town.

It’s Xmas. Henry, can you read the post?

Yeats did not die here—died in France, they say,

brought back by a warship & put down.

Joyce died overseas also but Hopkins died here:

where did they plant him, after the last exam?

To his own lovely land

did they rush him back, out of this hole unclear,

barbaric & green, or did they growl ‘God’s damn’

the lousy Jesuit, canned.

This Dream Song juxtaposes the deaths of Hopkins with that of Yeats and Joyce, both of whom died outside of Ireland, as well as the death of Jonathan Swift, who, though born in Dublin, suffered a stroke in 1742 and “thought himself as despairing in exile.” This tribute to Hopkins occurs near the end of The Dream Songs, following one in honor of a beloved dean of Princeton, who died alone win Penn Station in New York, surrounded by strangers, and Dream Song # 378, which might be considered Berryman’s effort to rewrite “Spelt from Sibyl’s Leaves.” The Irish Jesuits, as continues to be our Jesuit custom today, did not repatriate the body of Hopkins to England after his death on June 8, 1889, at age forty-four, after having contracted typhoid fever. If the rather shocking word “canned” in the poem refers to Hopkins’s coffin in the communal Jesuit gravesite at Glasnevin Cemetery—suggesting that Hopkins’s body was sealed in a jar, as in canned peaches, or perhaps as someone talking who lacks originality or individuality, as in a canned speech—then Berryman is emphasizing the disinterest and lack of appreciation for this poet by his fellow Jesuits. Years before, in 1884, Hopkins had been sent to Dublin as a professor of Greek at the new University College and as an examiner in the Royal University, and while he made friends in Dublin and beyond, he found grading student papers an exhausting task, no doubt an important factor in his lapse into depression in 1885. The “terrible sonnets,” a group of poems in which Hopkins struggles with problems of religious doubt, embody cries of excruciating anguish, especially two written in 1885: “I wake and feel the fell of dark, not day” and “No worst, there is none.” With echoes of Jeremiah 12:1 and Lamentations 3:12, Hopkins asks in these sonnets why the wicked prosper, as he feels led not into light, but into terrible darkness. Yet, the terrible sonnets need always be juxtaposed with some sort of overall evaluation of Hopkins’ life and works, by highlighting the importance of such poems as The Wreck of the Deutschland, “The Habit of Perfection,” “The Starlight Night,” “Spring,” “That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire and the Comfort of the Resurrection,” “To what serves Mortal Beauty?” and “The Leaden Echo and the Golden Echo.” Hopkins’s last words, “I am so happy, I am so happy,” are “as rich and resonant as any words in his poems; these words offer a multilayered commentary on his life and reputation.” The final few years of Berryman’s life, likewise filled at moments with unease and despair, were also quite productive from a literary point of view. As he reached within himself to find some spiritual center, he continued writing his Dream Songs, in addition to two posthumous works: a volume of poetry called Delusions, Etc. (1972) and a novel about addiction, entitled Recovery (1973). He even began to express his belief that the God who rescued the abandoned did exist: “He saves men from their situations, off and on during life’s pilgrimage, and in the end,” he said in the summer of 1970 in an interview with Peter Stitt, a former student. “I completely bought it,” he added, “and that’s been my position since.” While reading more about theology and the Church, Berryman said he was deeply interested in Christ, though he did not pray to him. “He certainly was the most remarkable man who ever lived. But I don’t consider myself a Christian. I do consider myself a Catholic, but I’d just as soon go to an Episcopalian church as a Catholic church. I do go to Mass every Sunday.” He might have added, “and sometimes to a synagogue on Saturday.” From early May until mid-June 1970, Berryman was in the Intensive Alcoholic Treatment Center at Saint Mary’s Hospital in Minneapolis, after which he wrote a wonderfully lucid Hopkinesque tribute to God, entitled “Eleven Addresses to the Lord,” which reflect a type of religious conversion that became Part Four of his volume of poetry entitled Love & Fame (1970). His friend and fellow poet, Robert Lowell, commented forthrightly on this prayer sequence: “The prayers are a Roman Catholic unbeliever’s, seesawing from sin to piety, from blasphemous affirmation to devoted anguish.” Berryman’s stunningly simple First Address replaced his fractured trauma with a haunting, plain-spoken, poetic calculus accessible even to those unfamiliar with his life and works:

Master of beauty, craftsman of the snowflake,

inimitable contriver,

endower of Earth so gorgeous & different from the boring Moon,

thank you for such as it is my gift.

I have made up a morning prayer to you

containing with precision everything that most matters.

‘According to Thy will’ the thing begins It took me off & on two days.

It does not aim at eloquence.

You have come to my rescue again & again

in my impassable, sometimes despairing years.

You have allowed my brilliant friends to destroy themselves

and I am still here, severely damaged, but functioning.

Unknowable, as I am unknown to my guinea pigs:

how can I ‘love’ you?

I only as far as gratitude & awe

confidently & absolutely go. I

have no idea whether we live again.

It doesn’t seem likely

from either the scientific or the philosophical point of view

but certainly all things are possible to you,

and I believe as fixedly in the Resurrection-appearances to Peter and to Paul

as I believe I sit in this blue chair.

Only that may have been a special case

to establish their initiatory faith.

Whatever your end may be, accept my amazement.

May I stand until death forever at attention for any your least instruction or enlightenment.

I even feel sure you will assist me again, Master of insight & beauty.

The Sixth Address reflects a religious sensibility, personally confessional:

Under new management, Your Majesty:

Thine. I have solo'd mine since childhood, since

my father's suicide when I was twelve

blew out my most bright candle faith, and look at me….

Then my poor father frantic. Confusions & afflictions

followed my days. Wives left me.

Bankrupt I closed my doors. You pierced the roof

twice & again. Finally you opened my eyes.

My double nature fused in that point of time

three weeks ago day before yesterday.

Now, brooding thro' a history of the early Church,

I identify with everybody, even the heresiarchs.

These uplifting poems, written before committing suicide by jumping off a bridge near the University of Minnesota in January 1972, force one to ask an important question:

What did Berryman think about suicide?

Perhaps the answer can be found in the following passage he underscored in a copy of the 1967 A New Catechism: Catholic Faith for Adults: “As regards suicide, this is sometimes the result of hypertension or depression, and we cannot pass judgment.”

But what did he think about his own poetic accomplishment? The answer can be found in his

Tenth Address:

Father Hopkins said the only true literary critic is Christ

Let me lie down exhausted, content with that.

Endnotes

1. See Mariani, Furthermore, Berryman maintained that while Lowell, Hopkins, and Pound were equally important to him, he would not choose between them, though his rivalry with Lowell provided him “a continuing stimulus to originality.” See Matterson, 9. Also, McClelland, David, John Poltz, Robert Shaw, Thomas Stewart.“An Interview with John Berryman.”

2. John Berryman, We Dream of Honor, 70.

3. See Berryman, We Dream of Honor, 99. Berryman heard Eliot lecture on November 13, 1936 at the English Club on Mill Lane in Cambridge. He had a chance to talk to Auden on November 15, 1936, after Auden had given a reading at the Spenser Society at Cambridge. He also had a chance to talk to Dylan Thomas who had given a reading at the Nashe Society in St. John’s College, Cambridge, at the beginning of March 1937 (see Haffenden, The Life of John Berryman, 82, 83, 88-89).

4. Mariani, 150.

5. See Mariani, 160.

6. Lowell, “For John Berryman.” Reprinted in Berryman’s Understanding, 67-68.

7. Stitt interview. Berryman incorrectly said “seven-line stanza.”

8. Quoted in Haffenden, John Berryman: A Critical Commentary, 183.

Bibliography

Berryman, John. Berryman’s Sonnets. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1967; Berryman’s Sonnets. Introduced by April Bernard. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2014. -----.

Collected Poems: 1937-1971. Edited and introduced by Charles Thornbury. New York: Farrar, Straus& Giroux, 1989. -----.

Delusions, Etc. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1972. -----.

The Dream Songs. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1969.

The Dream Songs. Introduced by W. S. Merwin. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2007;

The Dream Songs (complete edition of 77 Dream Songs and His Toy, His Dream, His Rest: 308 Dream Songs). Introduced by Michael Hofmann. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2014. -----.

His Toy, His Dream, His Rest: 308 Dream Songs. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1968. -----.

Homage to Mistress Bradstreet. Partisan Review 20, no. 5 (September-October 1953): 489-592;

Homage to Mistress Bradstreet. With drawings by Ben Shahn. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1956. --

Love & Fame. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1970. -----.

77 Dream Songs. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1964. -----.

Recovery. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1973. -----.

“The Ritual of W. B. Yeats.” Columbia Review 17, nos. 4-5 (May-June 1936): 26-32. -----.

We Dream of Honor: John Berryman’s Letters to His Mother. Edited by Richard J. Kelly. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1988.

Berryman’s Understanding: Reflections on the Poetry of John Berryman. Edited by Harry Thomas. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1988.

Ciani, Daniela M. “Gerald Manley Hopkins and John Berryman.” In Gerald Manley Hopkins: Tradition and Innovation, 205-21. Edited by P. Bortalla, G. Marra, F. Marucci. Ravenna, Italy: Longo Editore, 1991.

Eilor, Sharon. Form after Whitman: A Lateral Step to Hopkins, Berryman, and the Art of Strict Wildness. Master’s Thesis. University of Montana, 1998.

Feeney, Joseph, S.J. “Praise Him: Celebrating the Life and Work of Gerard Manley Hopkins.” America 212, no. 12 (April 6, 2015): 14-17.

Haffenden, John. John Berryman: A Critical Commentary. New York: New York University Press, 1980. -----. The Life of John Berryman. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1982.

Hopkins, Gerard Manley, S.J. The Poetical Works of Gerard Manley Hopkins. Edited by Norman H. MacKenzie. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Kelly, Richard. John Berryman’s Personal Library: A Catalogue. Washington, D.C.: Peter Lang, 1999. Matterson, Stephen.

Berryman and Lowell: The Art of Losing. Totowa, NJ: Barnes & Noble, 1988.

Montague, John. “John Berryman: Henry in Dublin.” In The Figure in the Cave and Other Essays. Edited by Antoinette Quinn, 200-07. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1989.

Mariani, Paul. Dream Song: The Life of John Berryman. New York: William Morrow & Company, 1990. McClelland, David, John Poltz, Robert Shaw, Thomas Stewart. “An Interview with John Berryman.” Harvard Advocate 103, no. 1 (Spring 1969): 4-9. Reprinted in Berryman’s Understanding, 3 – 17.

Murray, Gerry. “Gerard Manley Hopkins: His Influence on John Berryman.” Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review 85, no. 338 (Summer 1996): 125 – 35.

Pick, John. Gerard Manley Hopkins: Priest and Poet. New York: Oxford University Press, 1942.

Stitt, Peter. “The Art of Poetry XVI: John Berryman 1914 – 1972.” Paris Review 14, no. 53 (Winter 1972): 177 – 207. Web: https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/4052/john-berryman-the-art-of-

poetry-no-16-john-berryman. Writers at Work: The Paris Review Interviews. Fourth Series. Edited by George Plimpton. Introduced by Wilfrid Sheed. New York: Viking, 1976.

Lectures by Patick Samway SJ available in The Hopkins Archive

- Percy Walker - Influence of Gerard Manley Hopkins (2003)

- Flannery O'Connor's Jesuit Influence(2004)

- De Vere and Hopkins

- Percy Walker and Hopkins Poetry

- New Testament in the Poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins

In 2017, Father Samway was awarded the Newbridge Silver Award in recognition of outstanding contribution to the work of The Gerard Manley Hopkins Festival