The English Church when Hopkins became a Catholic

This Lecture was delivered at the Hopkins Literary Festival July 2013Reverend Douglas Grandgeorge,

New York.

For 42 years, American poet Emily Dickinson and English poet Gerard Manley Hopkins< were alive at the same time, from his birth in 1844 until her death in 1886. Both were decidedly imaginative writers, each of whom developed a highly inventive style unique to themselves and almost impossible to duplicate. Neither knew of the other’s existence. Both struggled with despondency, and both found peace of mind in the cultivation of an exquisite lyrical art form. Dickinson’s works were seldom published in her lifetime, but when she died, her sister found more than 1000 lyrics in her bedroom bureau. Many a sister would have thrown the works away in a general clean-up, but Lavinia<, Emily's younger sister, discovered her cache of poems and recognized them for what they were—so that the breadth of Dickinson's work became apparent. It is frightening to imagine the loss which would have resulted from the destruction of her beribboned manuscripts, as she is now universally considered to be one of the most important and original of American poets.

It is therefore not a stretch for an American to wish that Hopkins had never converted to Catholicism. Had he become an Anglican divine, it is almost certain that we would have more poetry. His holy orders discouraged his writing in several ways: he was encouraged to think of his poetry-writing as self-indulgent and even sinful; his work load was very severe and tiring, giving him less time for writing; the foul drains which likely contributed to premature death would not have been tolerated in England as they were known to spread typhoid; and a great many of his poems were destroyed at his death—the entire contents of a five-drawer chest, containing papers, letters, drawings, and poems were straightaway burned.

None of this would have occurred had he been contented to be a high-churchman in the Church of England. He almost certainly would have held a professorship in classics at Oxford. His poetic genius would have been encouraged rather than discouraged. He would have been a man of leisure to write, very probably a bishop with a consequent seat in the House of Lords. It is therefore useful to look at what it was about the English church in the Mid-nineteenth Century that would make a poetic prodigy feel the necessity to leave it at the age of 22.

A Time of Change in the Church of England

From 1800 to about 1870, the English church experienced a more rapid change than it had experienced since the Reformation<. Many other denominations were now on the scene, and in 1828 Protestant dissenters were able to be elected to Parliament on equal terms with members of the Established Church. It could be said that in the years of Hopkins’ life, the Church of England went from being the Established Church to being a denomination among others. This inevitably led to a feeling that all religious expression was equal to another, and that there was no “one way” to experience or worship God. The idea of a transcendent God Who was approachable through the Church declined, and the English government began stripping it of both spiritual and temporal authority.

At the same time clerical life had sunk into worldliness, and in some cases vice and depravity. Hundreds of examples could be given, but in this setting a typical few will suffice. In 1831, Bishop John Kaye< wrote: “We cannot be surprised at being told that the Church’s days are already numbered, and that it is destined to sink at no distant period before the irresistible force of enlightened public opinion.”

Although a Church Discipline Act< was passed in 1840 to give bishops more power to remove recalcitrant clergy, its impact was inadequate. It was passed to address concerns of parishioners which were most extensive. One unfortunate example was that of John Bewicke,< rector of Hallaton.

A parishioner charged that he never wore a gown or bands, never knelt for prayers, even though he was in every way able-bodied, hardly ever preached, and performed communion in colored gaiters. A Mrs. Hickman< had been seen entering his bedroom by a ladder. He often missed church in a parish where only seven or eight out of 800 members attended.

Similarly John Willis<, rector of Haddenham, was accused of visiting a brothel in Aylesbury, of preaching while intoxicated, and having been thrown out of a pub in High Wycombe for drunkenness. Willis pled guilty to all counts, and the bishop deprived him of his living for one year, a minor inconvenience, as he had a private income of £800 and very much enjoyed his one-year vacation from his parish duties.

A one-year suspension was the severest disciplinary action a bishop could inflict even under the Discipline Act. A common problem was that clergy were usually educated at Cambridge or Oxford and were expected to be gentlemen—riding to hounds, entertaining lavishly, especially their wealthier parishioners, while simultaneously preaching the gospel of the humble Jesus.

Francis Massingberd< wrote in his diary on September 12, 1839: “Yesterday had a large dinner party, 12—too many, vulgar and inelegant in itself and questioned the lawfulness to a clergyman…Call not thy rich neighbors, but call the poor.” Yet Massingberd<’s observation and sentiment may have reflected a minority position.

Out of this situation came the Oxford movement, calling the church back to its original purpose and acquired grandeur—cherishing something that had always been present in the English church to some degree since the Reformation—caring more for its Catholic heritage than the Protestant reforms. The Oxford men wrote tracts in which they called for beauty in worship, bringing back candles, incense, and exquisitely embroidered vestments. They prized the writings of the Church Fathers<, reintroduced the mystery of the Eucharist, and revived the supreme importance of the apostolic succession.

Although a very large majority of those moved by the Tractarians<, as they were also called, remained in the Church of England, some, including the theological giants, John Henry Newman< and Henry Edward Manning<, took the obvious course and made their submission to Rome.

Another factor, which has never been properly explored, was the fact that Victoria< was the titular Head of the Church of England<. Victoria was Queen during the whole of Hopkins’ life. And a much-loved Queen she was. But she was a woman: a wealthy, privileged young virgin; then a devoted wife; truly a loving mother to nine children; at last for many years a grieving widow. She was Queen because she inherited the office as a descendant of George III. She appointed the Archbishop of Canterbury< and all bishops, all of whom had to be men. All priests were men.

The Bishop of Rome<, on the other hand, was a male priest, elected by men who represented the apostles and claimed to be successors to them.

There was, to be sure, much about the Church of England to be admired. Her art and architecture, her music and hymnody, the King James Bible< and the Book of Common Prayer,< but in the Nineteenth Century, the mysterium was absent, the clergy could not bring it back because, for the most part, the clergy no longer believed in it, and for Hopkins, that was a certain path to the trivialization of human life and the absence of God. The Incarnation in Christ and its continual repetition at the altar saved him from atheism and despair over the human condition.

J. Hillis Miller suggests: “Hopkins’s conversion is a rejection of three hundred and fifty years of the spiritual history of the West, three hundred and fifty years which seem to be taking men inexorably toward the nihilism of Nietzsche’s ‘Gott ist tot.’”

In order to avoid the absence of God in the world, Hopkins is willing to give up family, position, sexuality, worldly honor, even his art. He died happy, but we have much to mourn.

Bibliography

Owen Chadwick<,History of The Spirit of the Oxford Movement<, Cambridge U. Press, 1990.

Lawrence N. Crumb, The Oxford Movement and Its Leaders<, American Theological Library, 1988.

Geoffrey Faber,< Oxford Apostles<, Faber & Faber, London, 1933.

Eugene R. Fairweather,< ed., The Oxford Movement<, Oxford University Press, New York, 1964.

Kenneth Scott Latourette, Christianity, <Harper & Brothers, New York, 1953.<

Justus George Lawler, Hopkins Re-Constructed<, Continuum, New York and London, 1998.

Paul Mariani, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Viking, New York, 2008.

Hillis Miller, The Disappearance of God<, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1963.

William George Peck,Social Implications of the Oxford Movement<, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York and London, 1933.

Walter Walsh, The Secret History of the Oxford Movement<, Swan Sonnenschein, London, 1897.

Norman White, Hopkins, A Literary Biography<, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1992.

Lectures from 2013 Hopkins Festival

Hart Crane and Gerard Manley Hopkins

Love in the Writing of Gerard Manley Hopkins

Hopkins and the Church of England

Meister Eckhart and his Influence on Gerard Manley Hopkins

Lectures from GM HOPKINS FESTIVAL 2023

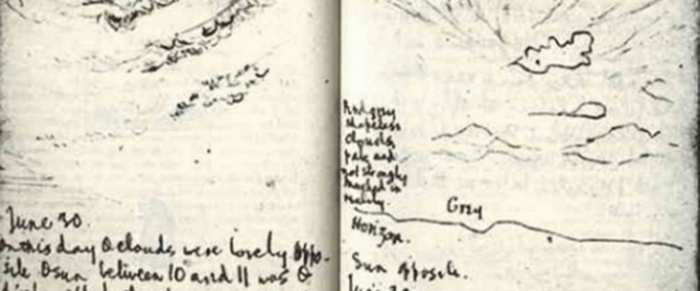

- Vision and perception in GM Hopkins’s ‘The peacock’s eye’ Katarzyna Stefanowicz Gerard Manley Hopkins’s diary entries from his early Oxford years are a medley of poems, fragments of poems or prose texts but also sketches of natural phenomena or architectural (mostly gothic) features. In a letter to Alexander Baillie written around the time of composition He was planning to follow in the footsteps of the members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood who had been known for writing poetry alongside painting pictures ... Read more

- Hopkins Trees and Birds Margaret Ellsberg Margaret Ellsberg discusses Hopkins's connection with trees and birds, and how in everything he wrote, he associates wild things with a state of rejuvenation. In a letter to Robert Bridges in 1881 about his poem “Inversnaid,” he says “there’s something, if I could only seize it, on the decline of wild nature.” It turns out that Hopkins himself--eye-witness accounts to the contrary notwithstanding--was rather wild. Read more

- Joyce, Newman and Hopkins : Desmond Egan

- Joyce's friend, Jacques Mercanton has recorded that he regarded Newman as ‘the greatest of English prose writers

’. Mercanton adds that Joyce spoke excitedly about an article that had just appeared in The Irish Times and had to do with the University of Dublin, “sanctified’ by Cardinal Newman, Gerard Manley Hopkins and himself. Read more ... - Hopkins and Death Eamon Kiernan -An abiding fascination with death can be identified in the writings of Gerard Manley Hopkins. Easily taken for a sign of pathological morbidity, the poet's interest in death can also be read more positively as indicating, his strong awareness of a fundamental human challenge and his deployment of his intellectual and artistic gifts to try to meet it. Hopkins's understanding of death is apocalyptic. ... As will be shown, apocalyptic thought reaches beyond temporal finality. Hopkins's apocalyptic view of death shows itself with perhaps the greatest consequence in those few works which make the actual event of death a primary concern and which, moreover, leave in place the ordinariness of dying, as opposed to portrayals of the exceptional deaths of saints and martyrs. Read more

Lectures from Hopkins Literary Festival July 2022

- Landscape in Hopkins and Egan Poetry Giuseppe Serpillo

- Walt Whitman and Hopkins Poetry Desmond Egan

- Emily Dickenson and Hopkins Poetry Brett Millier

- Dualism in Hopkins Brendan Staunton SJ

Hopkins's Manuscript Notebook

Lectures delivered at the Hopkins Literary Festival since 1987

© 2024 A Not for Profit Limited Company reg. no. 268039