JOYCE, NEWMAN and HOPKINS

Desmond Egan, Poet,

Artistic Director,

International Hopkins Literary Festival,

Joyce’s admiration for Newman is well documented. His friend, Swiss writer Jacques Mercanton (1910 - 1996) has recorded that, when they met in 1938, he still regarded Newman as ‘the greatest of English prose writers

’

‘I have read him a great deal and (in Ulysses) where all the authors are parodied,

Newman alone is rendered pure, in the grave beauty of his style.’

1 Mercanton adds that,

Joyce spoke excitedly about an article that had just appeared in The Irish Times and had to do with the University of Dublin, “sanctified’ by Cardinal Newman, Gerard Manley Hopkins and himself.

Newman, The Catholic University (UCD) 1873 — 1858

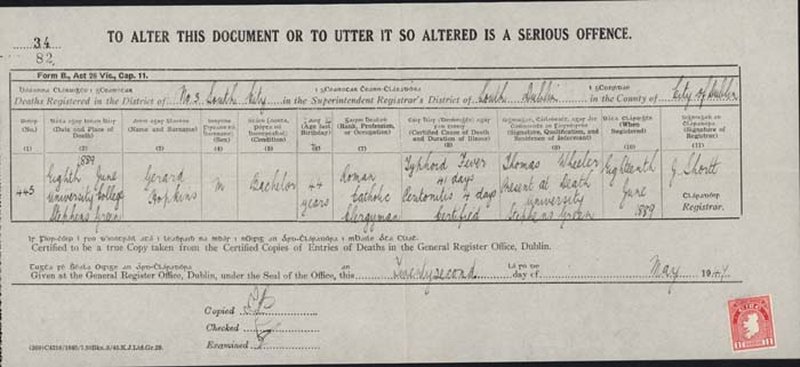

Newman had been brought over by the Irish Bishops to found, in 1873, the Catholic University (later UCD). He retired in November 1858. Twenty six years later, Hopkins — who had been received into the Catholic Church by Newman — came to the University on a Classics fellowship (February 1884) and died there on June 8, 1990, aged almost 45.

16 years later, Joyce (1882 — 1941) attended the University, attending from 1898 to 1902.

James Pribek SJ. 2 points out that there are no fewer than 41 textual allusions to Newman in all of Joyce’s writing.

These include:

- textual allusion in his university essay (1900);

- in Stephen Hero (1904-06);

- in A Portrait of the Artist (1907 — 14);

- in his play Exiles (1915);

- in Ulysses (1914 —21);

- and most of all, 12 in Finnegans Wake (1923 — 38).

Newman is also mentioned in letters of 1905, 1931,1935 (twice). Joyce considered him ‘the greatest of English prose writers’, a favourite to the end, the first in a list whom he asked to be read aloud to him by Paul Leon when Joyce was almost blind, for that ‘grave beauty’ and ‘the cloistral silverveined prose’ which his alter ego Stephen Dedalus so admired in A Portrait.

James Joyce and Gerard Manley Hopkins

Joyce also admired Hopkins, the man: speaking excitedly to Mercanton about that article in The Irish Times, He returned to Newman, about whom he spoke with great respect: “the Church will surely decide to make a saint of him”...3 (Pribek also adverts to the reluctance of some critics to acknowledge Joyce’s debt to Newman something which I had myself noticed in Ellman’s biography of Joyce, where Newman shamefully receives only three passing references, in a biography of 744 pages. A similar bias demeans Norman White’s biography of Hopkins). In Stephen Hero (1904 - 06: an early draft of A Portrait of the Artist) Dedalus defends Newman’s beliefs about literature and education and refers directly to five of Newman’s books : the Apologia, The Idea of a University, Discourses to Mixed Congregations, The Grammar of Assent and Callista. Chapter IV of A Portrait also refers to Newman: Stephen joins his siblings in singing to distract themselves from their poverty and miserable meal, And he remembered that Newman had heard this note also in the broken lines of Virgil, giving utterance, like the voice of Nature herself, to that pain and weariness yet hope of better things which has been the experience of her children in every time. (p.164) The line in question comes from Newman’s Apologia pro Vita Sua.

As Pribek summarises it, 'Though Newman the artist is an obvious mentor for Stephen in the Portrait, Newman the priest never eases

exerting his influence over the young man'.

4

Newman is referred-to seven times in Ulysses (1914 — 21), most notably in chapter 14: ‘The Oxen of the Sun’. Here Bloom enters Holles Street Maternity Hospital to enquire after a friend, Mina Purefoy. One birth becomes an evocation of the birth of Prose. The evolution of the English language mapped in this episode equates with the growth of the fetus in the womb and the style of the chapter, mimics the development of English from its beginnings through various masters, and in their style of writing.

Coming to modern times, Joyce writes in the style of Newman (p. 552) but, as he pointed out to Mercanton, though he parodied the style of other writers including Pater and Ruskin , he respects ‘the grave beauty of his (Newman’s) style’. Joyce even introduces Newman’s poem, Lead Kindly Light

, in Molly Bloom’s famous monologue at the end of Ulysses,

he got me on to sing in the Stabat mater by going around saying he was putting Lead Kindly Light to music I put up to that till the jesuits found out he was a freemason thumping the piano lead thou me on copied from some old opera yes... (p. 886)

Joyce’s friend and memoirist Frank Budgeon who wrote a famous guide to Ulysses, says of Finnegans Wake

, that

its ‘major theme’ is the resurrection.5 The idea is relevant both to Newman and - as we shall later see — to Hopkins. Newman’s presence is strongly there: critics have counted 12 references to him, but the strongest occur in a group towards the end, early in the 17th chapter, where Earwicker begins to wake up: Array! Surrection! Eireweeker... (p.593).

As Pribek points out,

The passage then plays upon a line that Joyce lifted from Newman’s Apologia, which Newman had borrowed from St. Augustine: securus iudicat orbis terrarum... ‘Untroubled, the world passes its judgment’ - which helped Newman become a convert to Catholicism.

Joyce later puns on the Latin: ‘securest jubilends albas Temoram”- Temora being the title of an ancient epic poem by Scottish poet and writer James Macpherson (1736 — 96) based on the Irish epic of Fionn and the Fianna. 6 On the following page Joyce again refers (movingly, it seems to me) to Newman’s poem‘Lead Kindly Light’, light kindling light has led we hopas but hunt we the journeyon....(594) Mercanton tells us 7 that Joyce later commented, on the Wake Oh you will see. Those last pages are simple, banal. The mystery is gone. It is daylight again. In all, Joyce refers to 'Lead Kindly Light' six time: twice in Ulysses and four times in the Wake.

Lead, Kindly Light, amidst th’encircling gloom,

Lead Thou me on!

The night is dark, and I am far from home,

Lead Thou me on!

Keep Thou my feet; I do not ask to see

The distant scene; one step enough for me...

I find the last pages of the Wake quite moving, even revelatory.

11: Joyce and Hopkins

Here I can mainly summarise what may be found in my book, Hopeful Hopkins. 8 It is generally true that the Modernists, led by Yeats, Pound and Joyce, tended to ignore or overlook Hopkins, especially early on. Writing to Margaret Ruddock in 1935, Yeats confesses,

I hate Gerard Manley Hopkins, but people quite as good as I am admire him. He belongs to the move ment immediately before mine...my movement ... was the escape from artificial diction. 9

In the Introduction to his 1936 Oxford Anthology of Modern Poetry he admits,' I read Gerard Hopkins with great difficulty...etc.' 10

Nevertheless, Yeats reluctantly included some Hopkins poems in his notoriously partisan Anthology of 1936 (three years before Joyce died). Hopkins’s poetry had gained a reputation from its first publication (1918) and after a second Collection appeared, (1930) Hopkins began to attract a world-wide following.

Wyndham Lewis (1882 — 1957) novelist-friend of Joyce and Pound, in an interview in 1931 even mentions Hopkins in the company of John Donne as an exemplar of ‘high standards’.

At the G. M. Hopkins Conference in 1997, Hugh Kenner (a noted Joyce scholar) asserted (and his comment recorded) that, Joyce, so far as we can tell, never chanced to hear of Hopkins. For once, Kenner was not quite right. Hopkins was certainly heard-about and Joyce was well aware of him. Herbert Gorman’s biography, James Joyce (New York 1939) written at the prompting of Joyce, suggests as much. Writing about the Faculty in University College, Gorman refers to ‘the famous Father Gerard Manley Hopkins’ and later adds that the Aula Maxima was ‘hallowed by the memories of Cardinal Newman, Father Manley Hopkins and James Joyce(!). The names, however, are not, from one point of view, incongruous’ 11(11) Joyce, in Finnegans Wake, jokingly refers to Gorman’s book as ‘The Martyrology of Gorman’ (FW 349). He must have read this study of his work, the writing of which he had himself initially promoted. He kept a copy of the book and even asked Mercanton to send Gorman - when he was planning a second edition - a newspaper clipping in which Joyce was mentioned, as of use in the revised edition.

We would have expected Joyce to know about Hopkins anyway: the Jesuit-cum-Dublin link alone would have interested him. Joyce attended Clongowes from 1888 to 1891 (Hopkins had made a retreat in Clongowes in 1885 and composed three poems, "Carrion Comfort", "To What Serves Mortal Beauty" and "The Soldie" there).

Joyce attended Belvedere College from 1893 to 1898; and went on to the Jesuit-run Catholic University (where Hopkins had taught from 1884 to 1889) for 3 years: some 12 years in all of Jesuit teaching. His friend Padraic Colum told the present writer (in 1971) that Joyce always looked on himself as ‘a Jesuit boy’ - something which emerges strongly from Padraic and Mary Colum’s Memoir, Our Friend, James Joyce (12) ‘You ought to allude to me as a Jesuit’ he once remarked to Frank Budgen, a Zurich friend (1918/19) and memoirist (13) The Catholic University, — now Newman House and part of U.C. D. - was where Hopkins lectured and also died.

This Dublin connection alone would have been enough for Joyce, who was obsessed by the city and — although his last visit there was in 1912 — never left it emotionally. Journalist Nino Frank (who has written the fullest account of Joyce’s life in Paris) said that Dublin, was ‘the deliberate setting of all that he wrote’ (14) As a party piece, Joyce would sometimes name the shops in O’Connell Street, in order. He always liked to meet Dubliners visiting Paris; like his friend Beckett, Joyce was a true Dub.

We have seen that Joyce was a special admirer of Newman. ‘I have read him a great deal’ Joyce remarked to Jacques Mercanton. Newman was on Joyce’s mind; Hopkins must have been too. (15) In Portraits of the Artist in Exile, Recollections of James Joyce by Europeans (edited by Willard Potts) there is proof that Joyce had actually read at least some of the Jesuit poet. Conversing with Jacques Mercanton

(died 1996) in Lausanne in 1938, Joyce,

spoke excitedly about an article that had just appeared in The Irish Times and had to do with the University of Dublin “sanctified” by Cardinal Newman, Gerard Manley Hopkins, and himself ... He paused at the word “sanctified”, which surprised and amused him: he thought that it applied to the other two but hardly to himself. (16).

So Joyce did know about Hopkins! His comparison with Mallarmé seems not unrelated to Yeats’s Modernist viewpoint of Hopkins as another old-fashioned pre-Raphaelite: Yeats’s view, may well have been pervasive. Stephan Mallarmé (1842 - 1898), the French Symbolist poet, was noted for his experimental approach, with a concentration on sound and on form - including the layout of the text - often at the expense of accessible meaning. Although his own mellifluous poems have never wholly escaped the charge of wilful obscurity, his style was highly influential (not only on poets, including on Yeats; on composers led by Debussy and Ravel; and on the work of such critics as Derrida, Lacan, Barthes and other Structualists). In placing Hopkins with Mallarmé then, Joyce must have thought of him as an experimenter, more concerned with sound effects than with content.

We know that Joyce was not correct in this. Hopkins’s was no mere ’metrical labour’, no focussing on mysteriousness or on the sub-conscious, such as preoccupied Mallarmé: Hopkins’s primary aim in his writing, as he told Bridges, was to express the layers of his thought and feeling, Obscurity I do and will try to avoid so far as is consistent with excellences higher than clearness at a first reading (letter from Stonyhurst, in 1878) 17. In this, he was driven at times to the edge of intelligibility - but he always tried, insofar as it was compatible with what he wished to express, to avoid being unintelligible. Joyce did not do him justice: Hopkins’s poems, for all their intricacy and experimental quality, were never exercises in art for art’s sake - that aesthetic of Art Nouveau, rejected by the Modernists - nor in obscurity for the sake of obscurity. That said, Hopkins’s poetry did clearly share one quality with the French poet’s work: a special attention to sound, a concern with rhythm, a musical quality which led Hopkins to emphasise in various letters that his poems be read aloud. Take, for example, his famous letter to Bridges in 1877: My verse is less to be read than heard... it is oratorical, that is, the rhythm is so.17 - and again in 1885, to Everard Hopkins: As poetry is emphatically speech, speech purged of dross like gold in the furnace, so it must have emphatically the essential elements of speech. 19 Finnegans Wake, with its multilingual puns, strong sonority, and musical structure should also be read aloud - as Joyce requested. The main concern of speech is not to mystify but to say something. Perhaps this is why Mallarmé, for all his undoubted importance, is not much read nowadays - whereas Hopkins is. One may well wonder which of Hopkins’s poems did Joyce have in mind when he compared him to the French symbolist; and wonder too, which poem had been compared to Joyce’s Work in Progress (later Finnegans Wake). Was it "The Wreck of the Deutschland"? Perhaps; it might also have been "That Nature Is a Heraclitean Fire and of the Comfort of the Resurrection". Detecting literary influence within a writer’s written work can be problematic - but it can also be revelatory. Michael McGinley, a scholar and admirer of Hopkins, finds a trace of Hopkins in Joyces’ Ulysses, published in 1922, 17 years before the Wake. McGinley evidences, from that novel, the sentences, God’s air, the All father’s air, scintillant circumambient cessile air... In her lay a Godframed Godgiven performed possibility... He suggests - not unconvincingly - that there are echoes here of lines from "The Blessed Virgin Compared to the Air We Breathe" William York Tyndall 20 convincingly points out a number of accommodated quotations from Hopkins in the Wake. These references, along with some other suggestions, are echoed by Robert Boyle S.J. in his study 21 while not disagreeing with the general opinion that there is little evidence that Joyce spent much time on Hopkins’s poems, nevertheless does highlight within the Wake some apparent references along with those adverted-to by Tyndall . (Surprisingly, neither White nor Martin, Hopkins’s most recent biographers, mentions this; nor does Ellman in his biography of Joyce. (22)

There are certainly a number of echoes of Hopkins in the Wake (composed between 1922 and 1938). On page 26 we even meet the phrase, But as Hopkins and Hopkins puts it... ‘Puts it’ suggests expression, writing; and on the same page there is a ‘falconplumes’. One can agree with Boyle that such a reference and such a compound certainly brings"‘The Windhove"’ to mind. Later, Joyce includes a direct reference to Sprung Rhythm, as a side-note to his text, The vortex. Spring of Sprung Verse. The vortex. 23 "Sprung Verse" we note, is introduced in capital letters i.e. treated by Joyce as a proper noun. Anyone interested in Hopkins would register that reference . Less obviously, perhaps, but arguably, there are other echoes here too. A couple of sentences further in the same section, the phrase, ‘The spearspid of dawnfire’, might seem Hopkinsesque not only in its compounding but in its imagery; and on the same page you find such equally suggestive compounding as ‘treadspath’; ‘paddypatched’; and another ‘flash’ in the phrase ‘a flash from a future of maybe’. Later, the phrase ‘Kwhat serves to’ certainly brings to mind Hopkins’s, "To What Serves Mortal Beauty?"; ditto with the later phrase ‘heaven electing’ which seems to echo ‘Elected Silence’ . Another sentence towards the end of Finnegans Wake ) While the dapplegray dawn drags nearing nigh for to wake all droners that drowse in Dublin.24 is more than a little suggestive of "The Windhover", with its ‘dapple-dawn drawn falcon’. Here, Joyce might even be including a sly dig at its Jesuit author-lecturer, droning and drowsing in St. Stephen’s Green.) Such phrases as ‘seasilt saltsick’ in the last few lines of F.W. 25 could bring "The Wreck of the Deutschland" to mind, not only in their imagery and compounding but equally in their heavy alliteration (think of that ‘dappledawn drawn falcon’). One of the final sentences, If I seen him bearing down on me now under whitespread wings like he’d come from Arkangels, I sink I’d die down over his feet, humbly dumbly, only to washup. might be seen to carry an echo of "God’s Grandeur", Because the Holy Ghost over the bent World broods with warm breast and with ah! bright wings Most notably of all: in the final chapter of the Wake we come across what seems to be an accommodated quotation from the Heraclitean Fire sonnet, with its ending, In a flash, at a trumpet crash, I am all at once what Christ is, since he was what I am... Here’s Joyce: a flasch and, rasch, it shall come to pasch, as hearth by hearth leaps live. 26 The reference to ‘pasch’ brings the Pasch, Easter, to mind; the time when Christ’s resurrection crowns the accounts of his Passion. That this line and that word should occur in the Resurrection section of the Wake is very striking. The last chapter is filled with Christian references, including the line , I only jope whole the heavens sees us.27 and after the strikingly sad, ‘is there no one who understands me? comes a section which includes the lines (partly quoted earlier) ‘Loonely in me loneness...I am passing out. O bitter ending! I’ll slip away before they’re up...If I seen him bearing down on me now under whitespread wings like he’d come from Arkangels, I sink I’d die down over his feet, humbly dumbly, only to washup ’. (28) The last phrase, one of the saddest in all literature, refers to much more than a river joining the sea, A way a lone a last a loved a long the I believe there is a case to be made for a deeper, more philosophical, reading of the Wake than the accepted one. But that’s another topic. There is also the tantalising possibility that Joyce actually saw some Hopkins poetry even before it appeared in that Bridges-edited 1918 edition. From a letter I came across in the Beinecke Library in Yale University, it emerges that Joyce’s mentor, Ezra Pound, had heard of Hopkins from the English novelist Maurice Hewlett whom Pound first met in 1909; some nine years before the Bridges edition of Hopkins appeared:

Hewlett heard of him from Bridges in 1912 or 11 but it is only in the last few years that he has had any proper recognition ... As I remember it, Hewlett had some proof=sheets (sic) or typescript or a rare out=of=print edition of Hopkins on Christmas of 1911 or 1912. He had had the work from Bridges who was interested in Hopkins as a fellow=student of quantitative metric. The samples, as I remember them, were not very interesting + certainly not up to the ‘Leaden Echo’. 29

Pound goes on on to type out meticulously and in full Hopkins’s poem (without "The Golden Echo"). Pound did not realise that the real innovator behind Bridges was Hopkins - which explains his initial preference for Bridges, whom he later came to reject as ‘Rabbit Britches’. By that time - the later 20’s - the vogue for Hopkins, was well in evidence and had been enthusiastically espoused by the Socialists and Communists whom Pound did not like. That Pound - and possibly his friends - might have begun to change his opinion of Hopkins might be gauged from his remark, in a letter of 1930 to Zukovsky, Look at G.M. Hopkins, he happened, not IN any current. Insulated and isolated. (England dif. state of things). 30 Pound’s daughter, Mary Pound de Rachewiltz (in a letter to the present writer) suggests that this remark indicates that her father evidently thought Zukofsky could learn from G.M. Hopkins. This I interpret as a positive opinion. Point taken. In a 1931 article in Criterion, the Editor Herbert Read - one of the first critics to promote Joyce - wrote an important critique of Joyce which Joyce must surely have read. In it, Read suggests comparisons between Hopkins, Pound and Joyce, pointing out that they had much in common. This, while Joyce was still working on Finnegans Wake and eight years before it was published. Joyce was well aware of Hopkins, as he also was of Newman. I rest my case.

NOTES

- Potts, editor, Portraits of the Artist in Exile, Washington, 1979, p. 217 Studies, Dublin, vol 93, 2004

- Potts op. cit. p. 217

- 3. Pribek, op. cit. 178

- 4. James Joyce and the Making of “Ulysses’, rep. Oxford, 1972, p. 352

- 5. This time (p. 593), Roland Mc Hugh in his Annotations to Finnegans Wake (Baltimore, 4th ed., 2016) Roland McHugh goes off the mark when suggesting - as poet Kevin McEneaney pointed out to me - that “genghis” is aka Newman, being compared to Genghis Khan, who is long gone, as will be the influence of Newman. McHugh goes on to suggest that this theme of dark doom for Newman leads to satire on Newman’s poem. To the end of his life, Joyce loved and admired Newman,.

- 6. Potts op cit. p. 218

- 7. Goldsmith, Newbridge, Ireland 2018.

- "Ah Sweet Dancer: W.B. Yeats-Margaret Ruddock: a Correspondence", ed.McHugh, London 1970, p.39

- 8.See Section 17 of Introduction

- 9. Herbert Gorman," James Joyce", New York, 1939, p.54

- 10. Padraic and Mary Colum, "Our Friend, James Joyce", New York, 1958

- 11. Gorman, op cit.

- 12 Potts, op.cit. p. 97

- 13. Potts, op. cit. p. 217

- 14. Potts, op. cit. p. 217

- 15. "Letter from Stonyhurst", 1878; "Selected Letters "ed. Phillips, Oxford 1991

- 16. Phillips, op.cit., p.90

- 17. Phillips, op. cit. p.218

- 18. Robert Boyle, "James Joyce’s Pauline Vision", Southern Illinois, 1978)

- 19. A reminder of Kenner’s own belief, strenuously repeated as he launched White’s Hopkins: A Literary Biography (Oxford, 1992) at the Gerard Manley Hopkins International Festival no. 6, 1993, that ‘There is no difference between any biography and a work of fiction; none!’ - a statement not challenged by White.

- 20. Page 292 of the Faber 1964 edition

- 21. p.585

- 22. p.628

- 21. p.628

- 22. p.594

- 23. p.628

- 24. Beineke Library Manuscript Department, box 106, folder 4454

- 25. "The Letters of Ezra Pound, 1907-1941" (Ed. by D. D. Paige) rep. 1971, New York