What was Hopkins’ favourite poem? St. Winefred's Well?

Lance Pearson,Actor,

Member of the Steering Group,

UK Hopkins Society.

The Hopkins Society UK

In the UK Hopkins Society, we sometimes ask readers of our Journal to tell us their favourite Hopkins poem. But what was Hopkins’ own favourite? Not the one he thought was the best (that was The Windhover), but the one he liked best, and cared most about. I venture to suggest it was one that very few people have even heard of – his unfinished play St Winefred’s Well (StWW). Precisely because it is unfinished, it lives in the <>‘Fragments’ section of his Poem, and receives far less attention than the finished works. The last couple of years have for me been a journey of discovering it. The only part of St Winifred's Well that Hopkins completed was the better known pair of companion poems,

The Leaden Echo and The Golden Echo. Because they make up one of the five poems about which Hopkins gave fullest directions for reading aloud, I included them in my 2012 lecture for the UK Hopkins Society on the instructions he gave for reading his poems. I threw out the suggestion that we might have a workshop some time for a performed reading of the whole play (as far as Hopkins had written it). The Committee called my bluff and booked me to do the autumn 2013 workshop. So I started studying the fragments in earnest. I discovered that what is for us an unfamiliar little failed project was for Hopkins the love of his life. From his first sight of St Winefred’s Well at Holywell in North Wales, early in his time at St Beuno’s, it captivated him, and the idea of writing a tragedy on the story of St Winefred grew to obsess him for the rest of his life. It was an ongoing favourite project lying behind all the more famous, completed poems that we know. And the three fragments of the play that have survived reflect faithfully the state of his life when he wrote them.

Holywell is about 7 miles from St Beuno’s, within walking distance. It is the oldest continuously visited pilgrimage site in Britain, sometimes known as the Welsh Lourdes. Hopkins made his first visit to it on 8 Oct 1874 with one of the other new trainee priests.

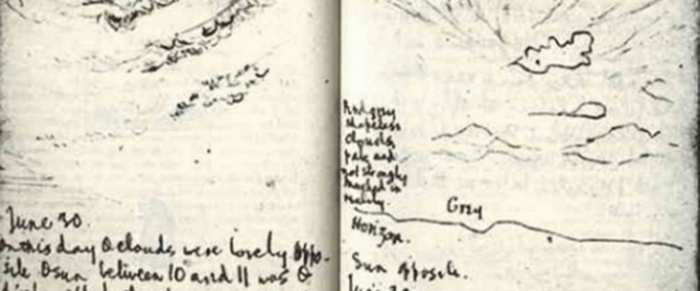

‘Barraud 'and I walked over to Holywell,’ he wrote in his Journal, ‘and bathed at the well and returned very joyously. The sight of the water in the well as clear as glass, greenish like beryl or aquamarine, trembling at the surface with the force of the springs, and shaping out the five foils of the well, quite drew and held my eyes to it. ... even now the stress and buoyancy and abundance of the water is before my eyes.’

The five foils represented the five-porched healing pool of Bethesda in John’s Gospel. His companion Clement Barraud later published two plays on saints, St Thomas of Canterbury and St Elizabeth of Hungary. So it is quite possible the two friends discussed the idea of writing a play on St Winefred there and then, or soon after. The well certainly took hold of Hopkins’ mind and became for him the most important place in Wales.

Two and a half years later, on 3 April 1877 (while still at St Beuno’s), he wrote to Robert Bridgesthat St Winefred’s Well

‘fills me with devotion every time I see it and would fill anyone that has eyes with admiration, the flow of aglaon hudor [Greek for bright water] is so lavish and so beautiful.’

That same year, still at St Beuno’s, he wrote two little 6-line poems about Winefred, one in English, the other in Latin, apparently as an inscription for a statue (no’s 139 + 175 in the Gardner / Mackenzie 4th edition.) There are also some unfinished fragments in Latin, continuing to reflect on the theme, presumably written around the same time (quoted and translated on pages 334-35 of the 4th edition). We hear nothing more in 1877-78, while he was teaching at Chesterfield and Stonyhurst (for the first time), and curating in London. But then in 1879 he writes to Dixon on 5 Nov: ‘I am thinking of a tragedy on St Winefred’s Martyrdom and have done a little.’ And he writes to Bridges that he has ‘a greater undertaking on hand than any yet, a tragedy on St Winefred’s martyrdom ...’; you can hear his excitement at the idea. He wrote those letters from Bedford Leigh, but it seems that the start he had made was actually while still at Oxford, those fruitful 10 months up to Oct 1879, during which he wrote, among others, Binsey Poplars, Duns Scotus’s Oxford, Henry Purcell and Peace.

To these we can add the first fragment (Fragment A) of St W W. It is a terse and businesslike introduction; the opening scene, setting up the rest of the play. We meet Winefred and her father, who tells her to get a room ready for her uncle Beuno (yes, none other than St Beuno) and his deacon. Winefred goes about her business, and her father tells us in a soliloquy how much he loves her, but has forebodings that he is going to lose her. Perhaps to gain further inspiration for the play, Hopkins spent that Christmas of 1879 a few weeks later back at St Beuno’s, rather than going home to his family as usual. On St Stephen’s Day, 26 Dec, he bathed in St Winefred’s Well which was, he recorded, ‘lukewarm and smoked in the frosty air’. We hear nothing more during Hopkins’ time in Bedford Leigh, Liverpool and Glasgow. But then in 1881 he writes to Dixon on 29 Oct from Manresa House in Roehampton. This was at the beginning of his tertianship, a one-year retreat concentrating on spiritual studies. He clearly hoped to make some headway with the play, because he writes:

‘If I do get hereafter any opportunity of writing poetry I could find it in my heart to finish a tragedy of which I have a few dozen lines written and the leading thoughts for the rest in my head on the subject of St Winefred’s martyrdom.’

The words hint at how important StWW was to him; and how frustrating, because, despite his hopes, there is no extant poetry from that year. Then in Sept 1882 he moved back to Stonyhurst for another spell of teaching. He wrote to his friend Alexander Baillie, ‘I like my pupils and do not wholly dislike the work’, but his mind was elsewhere.

Within a month he composed the Leaden and Golden Echoes – which perhaps not many people realise is the maidens’ chorus for the play. After the barren ‘silence’ of the tertianship, suddenly the dam was unblocked, and what did he write? His beloved play, of course. The writing is visionary and joyous, and wonderfully original; Hopkins said he was aiming to be musical and popular. How about this? It’s the girls’ celebration of God re-making our bodies to be young and beautiful – even our hair! – in the next life:

‘Give beauty back, beauty, beauty, beauty, back to God, beauty’s self and beauty’s giver. See; not a hair is, not an eyelash, not the least lash lost; every hair Is, hair of the head, numbered. Nay, what we had lighthanded left in surly the mere mould Will have waked and have waxed and have walked with the wind what while we slept, This side, that side hurling a heavyheaded hundredfold What while we, while we slumbered.’ (The Golden Echo, ll. 19-25)

At the same time he wrote his completed poems Ribblesdale and The Blessed Virgin compared to the Air we Breathe – completed and therefore generally known.

But he also wrote – though this is practically never recorded – what he called ‘Fragment C’ of StWW, for he mentions it in a letter of that December. This is Beuno’s beautiful monologue at the end of the story. It too pulses with the joyous creativity of this season in his life. It’s a hymn of praise to God set, as the heading tells us, ‘After Winefred’s raising from the dead and the breaking out of the fountain’ of healing water'. In the story, the spring and well miraculously arise on the very spot where Winefred‘s severed head fell when Caradoc killed her. And Beuno foresees the streams of pilgrims who will find joyful healing there:

‘As long as men are mortal and God merciful So long to this sweet spot, this leafy lean-over, This Dry Dean, now no longer dry nor dumb, but moist and musical With the uproll and the downcarol of day and night delivering Water ... Here to this holy well shall pilgrimages be, And not from purple Wales only nor from elmy England, But from beyond seas, Erin, France and Flanders, everywhere, Pilgrims, still pilgrims, more pilgrims, still more poor pilgrims. What sights shall be when some that swung, wretches, on crutches Their crutches shall cast from them, on heels of air departing ...’ (St Winefred’s Well Fragment C, ll. 10-14, 18-23)

So Hopkins had written the beginning and the end; now he wrestled with the body of the story. In 1884 he was appointed to Dublin, and his troubles began. His work was so frustrating and unfulfilling that he dreamed up many other abortive literary projects as well; but Winefred still haunted him. In April he wrote to Bridges, ‘I wish, I wish I could get on with my play.’ In Oct-Nov he started on Fragment B, which is Caradoc’s soliloquy after he has murdered Winefred. He worked on it intermittently through to April 1885. And this of course coincides with the lead-up to the agony of the terrible sonnets. Pages of successive drafts in his Dublin Notebook of that winter show that five years from when he had started writing, scarcely a line of this latest work had reached a shape which satisfied him. In January he wrote to Bridges:

‘I shall be proud to send you the fragments, unhappily no more, of my St. Winefred. And I should independently be glad of your judgment of them.

In April he sent more samples, from which we can see that he had made further progress in the intervening months, but clearly composition was a hard struggle. Bridges did his rather clumsy best to be encouraging, but he thought that what Hopkins had sent him was the finished product. Hopkins wrote back in May with characteristic exasperation: It is a hugely revealing passage. It anticipates the bleak words at the end of the Justus quidem sonnet (which begins

‘Thou art indeed just, Lord’): ‘birds build – but not I build; no, but strain, Time’s eunuch, and not breed one work that wakes. Mine, O thou lord of life, send my roots rain.’ (ll.12-14)

The one waking work that he could not breed, that he lamented so sadly, was not just any old poem in general, but was primarily his beloved lifelong St Winefred.

But Justus quidem was one of his last poems, written in March 1889, less than three months before he died. His words there are repeating the plea for fertilising rain which, as we’ve just seen, he’d written to Bridges four years earlier. That’s how long the play had lain lifeless in his barren womb. Justus quidem was his epitaph on the St Winefred project, which he now knew he would never complete. It echoes a sad little sentence he had written to Bridges six months earlier: ‘I think the fragments I wrote of St.Winefred, which was meant to be played, were not hard to understand.’ Although he had done some more work on it on holiday in 1886 when he said, ‘I hope to finish it ... I cannot say when’, he had had after all to give up. He says plaintively that it was ‘meant to be played’ i.e. performed, but he knew he would never see it done. As he contemplated the scenes he had not yet written, he confided to Bridges:

‘about the filling in and minor parts I am not sure how far my powers will go. I have for one thing so little varied experience. In reading Shakespeare one feels with despair the scope and richness of his gifts, equal to everything; he had besides sufficient experience of life and, of course, practical knowledge of the theatre.’

Shakespeare had big advantages denied to him. He came reluctantly to accept it was beyond him. He clearly felt deep disappointment at so relatively little written after so many attempts – the total is just 124 lines of the fragments and the 48 of the Echoes. And yet all is very far from loss. Hopkins never saw or heard the play performed; but on 12 Oct 2013 we, his Society of admirers in the UK, gave StWW what we think was its first and long overdue performed reading. In it we discovered and demonstrated that the so-called Fragment B, Caradoc’s soliloquy, is one of the greatest things Hopkins ever wrote, an absolute masterpiece. It is a feat of dramatic imagination, a dedication to evil, on a par with Marlowe’s Dr Faustus or Milton’s Satan. It had needed Hopkins to face the horrors ‘of dark, not day’, to be able to give Caradoc such a chilling and convincing character. Caradoc goes beyond complaining as Hopkins does in the terrible sonnets; he resists God and fights back.

‘I do not and I will not repent, not repent. The blame bear who aroused me. What I have done violent I have like a lion done, lionlike done, Honouring an uncontrolled royal wrathful nature, Mantling passion in a grandeur, crimson grandeur. Now be my pride then perfect, all one piece. Henceforth In a wide world of defiance Caradoc lives alone, Loyal to his own soul, laying his own law down, no law nor Lord now curb him for ever. O daring! O deep insight! What is virtue? Valour; only the heart valiant.’

(St Winefred’s Well Act II, ll 33-42)

It is another pearl to emerge from the pain of Dublin. Will it be performed again? Well, in England we have recently experienced the late birth of Elgar’s Third Symphony, and his ‘Pomp and Circumstance’ March No 6. They have been ‘completed’ from fragments that Elgar left at his death. More famously Mozart’s Requiem was completed by another composer, perhaps an assistant. Might there one day be a Hopkins disciple equipped to complete StWW? To take Hopkins’ fragments of the story, and then fill them out and round them off? It’s a thought.

Lance Pierson is an actor and poetry performer based in London . Lance is also a distinguished Member of the Steering Group of the Hopkins Society in the UK. He attended the International Hopkins Festival in Newbridge, for the first time in 2015 – and hopes to come again!