Gerard Manley Hopkins' Literary Critic

Elaine Murphy, L.G.S.M.Founder Member and Organiser of The Gerard Manley Hopkins Society.

Reading Hopkins over the years, I have been struck by the exact and exacting standards by which he judged certain works of art and literature. Clearly, he integrated these standards with his creative work as a poet and his priestly activities as a Jesuit. His had a dedicated and perceptive mind; a purity of heart. He explored his world with the delicate refinement of an Oxford scholar and a truthful, vigorous intellect. ˜There was single eye'.

In 1918, almost 30 years after his death, his ground-breaking poetry sprang through barriers of time and circumstance to enter the mainstream canon of English Literature at the highest rank. His letters are packed with literary and art criticism; poetical theory; opinions on architecture, language, music, philosophy, theology and even political comment.

Early Recognition of Hopkins critical powers

Hopkins's obituary published in The Nation on Saturday 15th June states:

As a professor, he aimed at culture as well as the spread of the knowledge of the facts of philology. His tastes were not confined to literature. He was a discriminating art critic, and his aesthetic faculties were highly cultivated.

This was written in 1889 long before his poetry or letters were published. When his letters were eventually edited and published, his biographer >Humphrey House wrote, they ˜showed him to be a general critic of literature—quite apart from all the technicalities—of wonderful insight and balance, detached enough to be free from current fashion, yet exactly aware of what contemporaries were aiming at and how they stood in comparison with the past

Claude Collier Abbott, who edited his letters, described him as an able, subtle, and honest critic. (P xvi) who ˜by transcending in great measure the dead conventions of his contemporaries is free of all ages and entombed by none'. (CCA1 xxi ) Hopkins letters are packed with literary and art criticism; poetical theory; opinions on architecture, language, music, philosophy, theology and even political comment. The bulk of Hopkins critical activity was confined to private correspondence and was neither written nor intended for a more public media. Thoughtful, and often delightfully forthright, it is addressed in the main to close friends Bridges; Dixon; Baillie, Patmore et al, and involved their personal and mutual literary activity. His opinions and judgments were his own, distilled and refined from his close observation of nature, his study of the classics and key literary and spiritual texts. His knowledge of contemporary art and culture was limited by the rigours of his college studies and later by priestly duties and discipline. He seldom managed to read newspapers or popular journals and often relied on the friends he corresponded with for news of current cultural publications. Criticism, Hopkins wrote to his friend, Alexandar Baillie (September 6th, 1863), when he was but 19 years old,

is a rare gift, poetical criticism at all events, but it does exist. You speak with horror of Shaksperian criticism, but it appears to me that among Shakspere's critics have been seen instances of genius, of deep insight, of great delicacy, of power, of poetry, of ingenuity, of everything a critic should have. I will instance Schlegel, Coleridge, Charles Lamb, Mrs. Jameson.

A perfect critic is very rare, I know.> Ruskin often goes astray; (example Whistler) Servius, the commentator on Virgil, whom I admire, is often too observant and subtle for his author, but nevertheless their excellences utterly outweigh their defects. The most inveterate fault of critics is the tendency to cramp and hedge in by rules the free movements of genius, so that I should say, according to the Demosthenic and Catonic expression, the first requisite for a critic is liberality, and the second liberality, and the third, liberality.

Art Ruskin and the Pre-Raphaelites

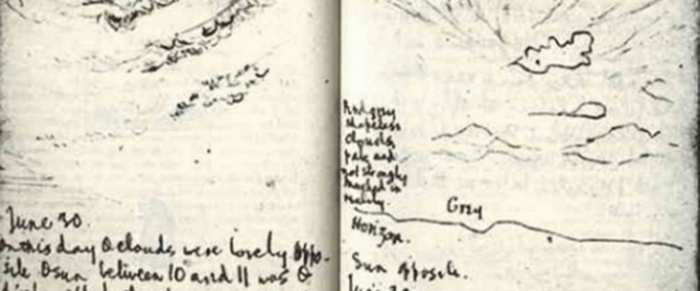

The youthful Hopkins despite winning the Governors Gold Medal for Latin verse, the Highgate School Poetry prize and an exhibition to Balliol College, Oxford, also entertained ambitions of becoming a painter and wrote to >Baillie 'I have now a more rational hope than before of doing something “ in poetry or painting. (CCA3 p.214 July 20 1864). There is plenty of evidence in his sketches and journal notes that he was indeed skilled in drawing and a keen observer of nature. Commenting on an aspect of one of his brother Arthur' drawings: (CCA3, p188 Nov 26th 1888) he notes that ˜Leonardo's La Giaconda (Mona Lisa) although perhaps the greatest achievement of modern art in the ideal treatment of the human face, is not quite regular in the conformation of the cheeks'. He advised his brother to carefully compose from life and then from life draw the draperies, and work at it till he had made the most perfect thing of it as he could. Hopkins was greatly influenced by John Ruskin (1819-1900) a profound critic of art and a profound social critic. However when Ruskin disparagingly commented on Whistler's work as ˜throwing the pot of paint in the face of the public' Hopkins upholds Whistler's striking genius - a feeling for what Hopkins called inscape' although admitting his execution was negligent, unpardonably so sometimes, which is perhaps what goaded Ruskin to comment as he did. Ruskin championed the then controversial painter Joseph Mallord Turner, as the artist who could most "stirringly and truthfully measure the moods of Nature." (David Piper's The Illustrated History of Art, p.321) Ruskin also championed the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood" who were formed in 1848 by Painters Dante Rossetti and William Holman Hunt and who were influenced by Ruskin's ideas. Hopkins was a great admirer of another Pre-Raphaelite Sir Edward John Millais whose three pictures exhibited in the Academy The Wolf's Den; ˜My first sermon'; ˜The Eve of St. Agnes had ˜opened his eyes. I see' he wrote ˜that he is the greatest English painter, one of the greatest of the world. One wonders if Hopkins judgment in this case was not a bit patriotic! Hopkins took pride in his nations achievement, as was natural:

A great work by an Englishman is like a great battle won by England. (¦) It will even be admired by and praised by and do good to those who hate England (as England is most perilously hated), who do not wish even to be benefited by her. ( CCA 3 to Baillie July 10. 1863)

Hopkins had met Edward Burne Jones another of the Pre-Raphaelite group at a friend's house with Christina and Maria Rossetti (Dante Rossetti's sisters). (CCA 3 July 20th 1864) To Baillie) he writes:no one admires more keenly than I do the gifts that go into Burne Jones's works, the fine genius, the spirituality, the invention; but they leave me deeply dissatisfied as well, (¦) It is their technical imperfection I can not get over, the bad, the unmasterly drawing (¦) Now this is an artist's most essential quality, masterly execution: and life must be conveyed into the work and be displayed there.

Of the poet Christina Rossetti, Hopkins commented later to his mother: ˜the simple beauty of her poetry cannot be matched') (CCA3 p 119: to his Mother, March 5, 1872) On Health and Decay in the Arts (An essay for the Master of Balliol 1864) P.74 (¦) ˜Truth and Beauty are the ends of Art and so far as it aims at these objectives or passes them by, so will it be successful or the reverse.' (¦) P.75 ˜Truth is not absolutely necessary for Art; the pursuit of deliberate Beauty alone is enough to constitute and employ an art'. Beauty, Hopkins thought, is reached by proportion, and though this golden mean must be reached by intuition, success in doing so is the production of beauty and is the power of genius. Truth and Beauty must be balanced for great Art. P. 75

Science is or might be concerned in it as well. Music and Architecture are two provinces of Art where proportion has more or less a scientific ground and character. (¦) P.79 ˜The arts', writes Hopkins, ˜present things to us in certain modes which in the higher shape we call idealism, in the lower conventionalism. (¦) the love of the picturesque, the suggestive, when developed to the exclusion of the purely beautiful is a sure sign of decay and weakness; Health and Decay in the Arts (Journal)

Literature Tennyson

A year later on the 10th September 1964, at the age of 20, Hopkins, again writing to Baillie in a lengthy letter, reveals he has begun to doubt Tennyson (poet laureate of much of the Victorian era) because of his use of Parnassian theories.

He presents a theory of how the language of verse may be divided into three kinds:

1.The first and highest is poetry proper, the language of inspiration. I mean by this, a mood of great, abnormal in fact, mental acuteness, either energetic or receptive, according as the thoughts which arise in it seem generated by a stress and action of the brain, or to strike into it unasked..

(2) The second kind I call Parnassian. It can only be spoken by poets, but it is not in the highest sense poetry. (œit does not sing). It does not require the mood of mind in which the poetry of inspiration is written. It is spoken on and from the level of a poet's mind, not as in the other case, when the inspiration which is the gift of genius, raises him above himself

(3) A great deal of Parnassian lowers a poet's average, and more than anything else lowers his fame I fear. The third kind (of poetry) he continues œis merely the language of verse as distinct from that of prose, Delphic, the tongue of the Sacred Plain, I may call it, used in common by poet and poetaster.

Hopkins has begun to doubt Tennyson because of his use Parnassian. (Hopkins to Dixon Feb.27, 1879) However, fifteen years later, Hopkins returns to the debate on Tennyson, this time with Dixon:

You call Tennyson ˜a great outsider'; you mean, I think to the soul of poetry. I feel what you mean, though it grieves me to hear him depreciated, as of late years has so often been done. Come what may he will be one of our greatest poets. To me his poetry appears ˜chryselephantine'*; always of precious mental material and each verse a work of art, no botchy places, not only so but no half wrought or low-toned ones, no drab, no brown-holland; but the form, though fine, not the perfect artist's form, not equal to the material. When the inspiration is genuine, arising from personal feeling, as In Memoriam, a divine work, he is at his best, or when he is rhyming pure and simple imagination, without afterthought, as in the Lady of Shalott, Sir Galahad, the Dream of Fair Women, or Palace of Art. But the want of perfect form in the imagination comes damagingly out when he undertakes longer works of fancy, as his Idylls: they are unreal in motive and incorrect, uncanonical so to say in detail and keepings. (¦) but for all that he is a glorious poet

Milton

Hopkins to Dixon (1) June 13 and (2) Oct.5th 1878

(1) Milton is the great master of sequence of phrase. (2) the great standard in the use of counterpoint: the choruses of Samson Agonistes are in my judgment counterpointed throughout; that is, each line (or nearly so) has two different coexisting scansions. His verse as one reads it seems something necessary and eternal (so to me does Purcell's music). Milton's art is incomparable, not only in English literature but, I shd. think, almost in any; equal, if not more than equal, to the finest of Greek or Roman. (¦) I found his most advanced effects in the Paradise Regained and, lyrically in the Agonistes, I have often thought of writing on them, indeed on rhythm in general; I think the subject is little understood

Keats

Hopkins to Dixon June 13th 1878

Keats genius was so astonishing, unequalled at his age and scarcely surpassed at any, that one may surmise whether if he had lived he would not have rivalled Shakespeare

Several years later, Hopkins, in defence of critical comments by Walter Patmore, and in agreement that Keats was no dramatist, draws attention to Keats's youth; his genius, intense in its quality; his feeling for beauty, for perfection, intense - stating he was at a great disadvantage in point of education compared with Shakespere. Their classical attainments may have been much of a muchness, but Shakespere had the school of his age. It was the Renaissance. (¦) Now in Keats's time, there was no one school; but experiment, division, and uncertainty. He was one of the beginners of the Romantic Movement, with the extravagance and ignorance of his youth. (Bridges Feb.15 1879) œFeeling, love in particular, is the great moving power and spring of verse.

Dryden

Hopkins to Bridges Nov 6th 1887 I can scarcely think of you not admiring Dryden without, I may say, exasperation. And my style tends always more towards Dryden. What is there in Dryden? Much, but above all this: he is the most masculine of our poets; his style and his rhythms lay the strongest stress of all our literature on the naked thew and sinew of the English language, the praise that with certain qualifications one would give in Greek to Demosthenes, to be the greatest master of bare Greek.

Writing Style

June 1 1886 to Bridges, For Hopkins, the touchstone of the highest or most living art is seriousness; not gravity but the being in earnest with your subject “ reality. H to Bridges August 14th 1979 Any writing style, he concludes, should be of its time (¦) the poetical language of an age shd. be the current language heightened. This was Shakespeare's and Milton's practice and he believed the want of it would be fatal to Tennyson's Idylls and plays, to Swinburne, and perhaps to Morris. (Dixon Dec 1 1881) He acknowledged Swinburne's genius was astonishing but thought him a strange phenomenon: ˜his poetry seems a powerful effort at establishing a new standard of poetical diction, of the rhetoric of poetry; but to waive every other objection it is essentially archaic, biblical a good deal, and so on: now that is a thing that can never last; a perfect style must be of its age. To Dixon October 12th 1881 he wrote: A true humanity of spirit, neither mawkish on the one hand nor blustering on the other, is the most precious of all qualities in style, and this I prize in your poems, as I do in Bridges'. After all it is the breadth of his human nature that we admire in Shakespeare to Patmore Oct. 20th 1887 CCA p.380 I make (a remark) now which will amaze you and, except that you are very patient of my criticisms, may incense you. It is that when I read yr. prose and when I read Newman's and some other modern writers' the same impression is borne in on me: no matter how beautiful the thought, nor, taken singly with what happiness expressed, you do not know what writing prose is.

At bottom what you do and what Cardinal Newman does is to think aloud, to think with pen to paper. The beauty, the eloquence, of good prose cannot come wholly from the thought. (¦) His (Newman's) tradition is that of cultured, the most highly educated, conversation; it is the flower of the best Oxford life. (¦) still he shirks the technic (sic) of written prose and shuns the tradition of written English. The style of prose is a positive thing and not the absence of verse-forms and pointedly expressed thoughts are single hits and give no continuity of style. I am coming to think much of taste myself, good taste and moderation, I who have sinned against them so much. But there is a prestige about them which is indescribable. (!!)

Hopkins, Social Critic

Hopkins was born in Stratford, Essex in 1884 during the reign of Queen Victoria. This period (1837 to 1901) a long and prosperous one for England and it brought numerous challenges to Christianity, including the growing trends of materialism, rationalism, Darwinism and communism, Despite ˜progress' it was an era of inequality and social injustice. Hopkins wrote to Bridges about his fears of social unrest. (CCA 1 p.27 August 2nd 1871), He was not silent on the issues which affected the ordinary working-class people. As a Jesuit priest, he was dispatched to minister to the poorest, most under-privileged in the cities and slums of Manchester, Liverpool, Glasgow and Dublin. He was deeply upset and concerned by what he saw and was heavily critical of the social reality: Horrible to say, in a manner I am a Communist'.He thought it just, though he did not mean the means of getting to it were. ˜It is a dreadful thing for the greatest and most necessary part of a very rich nation to life a hard life without dignity, knowledge, comforts, delight, or hopes in the midst of plenty which plenty they make. They profess that they do not care what they wreck or burn, the old civilisation and order must be destroyed. this is a dreadful look out but what has the old civilisation done for them? As it at present stands in England it is itself in great measure founded on wrecking. But they got none of the spoils, they came in for nothing but harm from it then and thereafter. England has grown hugely wealthy but this wealth has not reached the working classes; I expect it has made their condition worse. Besides this iniquitous order the old civilisation embodies another order mostly old and what is new in direct entail from the old, the old religion, learning, law, art, etc and all the history that is preserved in standing monuments. But as the working classes have not been educated they know next to nothing of all this and cannot be expected to care if they destroy it.

To condense a critical genius into a 20 minute talk might be brave, if not foolhardy, I admit, but I hope it will stimulate you to further explore the intellectual vigour of Hopkins writings.

Elaine Murphy L.G.S.M. The Gerard Manley Hopkins Society 28th July 2011 (GMH's Birthday) Elaine Murphy is a Licentiate of the London Guildhall School of Music & Drama, a founder member of The Gerard Manley Hopkins Society and an organiser of the Gerard Manley Hopkins International Festival

Lectures from Hopkins Literary Festival 2013

Hart Crane and Gerard Manley Hopkins

Love in the Writing of Gerard Manley Hopkins

Hopkins nad the Church of England

Meister Eckhart and his Influence on Gerard Manley Hopkins