A few lines of the Belgian and French novelist, poet, philosopher, psychoanalyst Henry BAUCHAU here serve as a fitting introduction to this lecture.

Why Hopkins and Schweitzer? I admit it is not so obvious, since Hopkins fits the image of a poet and Schweitzer of a man of action, an actor, we may say.

Rope imagery in poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins

Kimiko Hotta,

Japan

Rope imagery, recurrent in The Wreck of the Deutschland, appears in a variety of ways in four of Hopkins's Dublin poems written between 1885 and 1887, namely Spelt from Sibyl's Leaves, No worst, there is none; The Soldier, and Carrion Comfort.

In these poems, Hopkins juxtaposes the rope metaphor with other images in a seemingly unrelated manner, or he merely suggests the image without an explicit reference. This particular image, in other words, is treated as one of 'a phantasmal succession of unrelated images' (Peter Milward, Landscape, 84).

A Japanese perspetive — rope imagery in Hopkins Poems

Christina Rossetti & Hopkins: poets and Contemporaries

Kazuyoshi Enozawa,

Japan

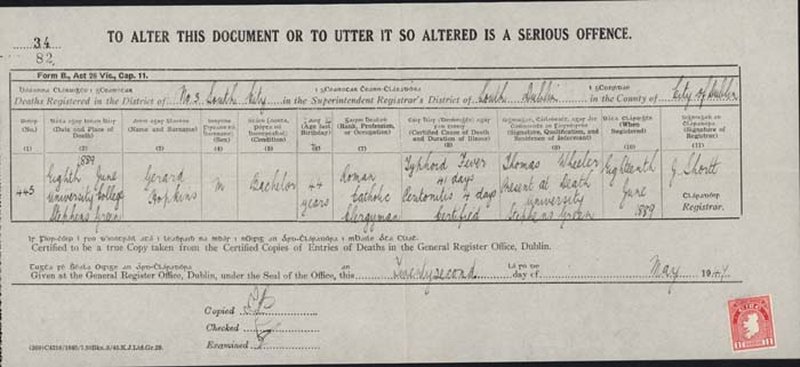

Gerard Manley Hopkins and Christina Rosseti may roughly be considered contemporaries, though not in the strict sense of the word. Born in 1844, Hopkins was fourteen years younger than Christina Rossetti, who was born in 1830. When the former died in 1889, the latter had five years more to live before expiring in 1894. During his relatively short life, Hopkins did not have much chance to meet this woman poet. In fact, he met her only once, it seems, and that was in July 1864, when he was introduced to her at the London house of his friend Ivor Gurney. More about Rossetti, Hopkins and Ivor Gurney

Aleksandra Kedzierska,

Instytut Anglistyki,

UMCS, Lublin,

Poland

Inscaping the heart, a recurring theme in the poetry of Hopkins,concerns itself with beauty, directs the reader heavenward. Inscape marked each stage of Hopkins's spiritual and poetic progression.

Inscaping the heart, a recurring theme in the poetry of Hopkins. The heart concerns itself with beauty, directs the reader heavenward. Its presence marked each stage of Hopkins's spiritual and poetic progression. The heart tells its tale of love. This essay, by Aleksandra Kedzierska, discusses heart imagery in the poetry of GM Hopkins.

In one of his juvenile pieces, Hopkins has his persona, Floris in Italy, express this wish: And I must have the centre in my heart/ To spread the compass on the all starr'd sky.(Floris in Italy) Almost like a motto to Hopkins's later works, these words point to the prominence of the heart which, ready as it is to concern itself with beauty, directs the reader heavenward. Recurring from poem to poem, its presence marked in each consecutive stage of Hopkins's spiritual and poetic progression, the heart seems to be telling its tale of love: the story of the man who after years of groping in the vacant maze of the Anglican Church, found, in Catholicism, the Real Presence of Christ to whom he dedicated his life and the fragile words of his poetry. In its attempt at reconstructing his story, this essay will discuss various representations of the `heart' image as they reveal themselves chronologically in Hopkins's poems.

More about heart imagery in Hopkins poems

Hopkins Imagery: Metaphysical or Physical?

Sakiko Takagi,

Tokyo,

Japan.

In 5th c. BC in Italy, many found Parmenides' concept of being new, outrageous and shocking, unbelievable even, because people had thought only of physical phenomena, physics. Gerard Manley Hopkins was so impressed with his theory that he dremained close to it throughout his life.

Hopkins and Parmenides

Problems Reading Hopkins Poetry in 2001

Frank Fennell,

Loyola University,

Chicago, USA

For over three decades now I have been a teacher and a scholar, both of which presume that I am also a reader. And it is as a teacher and a scholar that I am becoming increasingly unsure of what is going on when I exercise that role I share with so many others outside these professions, the role of reader. It seems to me that we know so little about what goes on when we read -- when we read, for example, a poem by Hopkins -- that our ignorance calls into question whatever we may have to say by way of criticism. So until we can give a better account of reading itself, it seems to me we will not make much headway in trying to explain or appreciate Hopkins or any other poet. In other words, we need to identify and overcome the obstacles to our understanding of what happens when we read, as a way of coming closer both to the poet and to ourselves. Problems of Reading Hopkins Poetry in 2001

Problems Reading Hopkins in 2001

The Natural World in writings of both Hopkins and Thomas Hardy

Meoghan Byrne Cronin,

St Anselm's College,

USA

In my mind, Gerard Manley Hopkins and Thomas Hardy met at St. Anselm College, during my interview for the position I hold now. In a typical New Hampshire blizzard, the professors were wearing dress jackets and snow boots. I was talking about my dissertation topic, specifically, Hardy's focus on folklore as a kind of openness to the power of the supernatural, a kind of space in which this world and a supernatural influence can meet. One of the department members was Dr. Gary Bouchard, a Hopkins scholar who lectured here a few years ago. Gary asked me, "How does this approach to the supernatural apply to Hopkins"? I thought to myself, "How should I know"? But I didn't say that. I talked about the natural world as bearing a charge created by the supernatural-a charge that an individual can access through faith, a habit of mind, or even through folk belief. But I didn't really think that this was a great answer. It was good enough for Gary, I guess. What did he know about Hardy? But I wasn't satisfied. Eight years later, for this lecture, I thought I might try to figure out a better answer.

Natural World in Writing of Hopkins and Thomas Hardy

Walt Whitman and Hopkins, Nature's Sons

Tamora Whitney,

Creighton University,

Omaha, Nebraska,

USA

Though differing greatly in terms of style and philosophy, Hopkins and Whitman share a love of nature. Their attention to particular details raises the ordinary and everyday to art, and they use the details of nature to, in their own way, glorify creation.

They both see in nature the handprint of God and see praising creation as a way to praise the creator. Their poetry shows God living in all of creation. Their philosophies differ, and though some of Hopkins' contemporaries saw stylistic similarities, he disagreed and so do I. But I see many similarities in subject matter and Hopkins himself in a letter to Bridges (October 18, 1882) said Whitman's mind was more like my own than any other man's living. As he is a very great scoundrel this is not a pleasant confession.

Walt Whitman and Hopkins, Nature's Sons

Links to Hopkins Literary Festival 2001