John Henry Newman and Hopkins

Ian Ker,Oxford University,

UK.

The young undergraduate Hopkins 'thought it was the greatest privilege' to be able to see John Henry Newman.

Hopkins had decided to become a Roman Catholic but stressed he had no wish to embrace 'a minimising Catholicism'.

He later wrote an account of his visit to his friend Robert Bridges

clearly pleasantly surprised that far from

being earnest and solemn Newman was humorous and light-hearted.

While Newman was on holiday in Switzerland

during August and early September 1866, the young undergraduate Hopkins wrote hesitantly to him at the Birmingham Oratory

on August 28, asking if he might intrude on the great man, rightly assuming that he was very busy and that he was 'much exposed to applications from all sides'. 1 What Hopkins did not know was that less than a month before while visiting Glion Newman

had at last realized where he must begin the argument of what was to become his philosophical magnum opus, An Essay in Aid of a Grammar of Assent (1870). Nor was Hopkins to know that seventeen years later as a Jesuit priest he was to write to Newman, by then a cardinal, to suggest that he should write a commentary on the book (an offer that Newman refused on the grounds that it would be an unnecessary labour). Newman had been thinking and making notes for the work for many years.

On his return home in the early hours of 7 September, his one thought must have been to commence work in earnest on the book. It is remarkable that only a week later on 14 September, with many letters to answer that had arrived during the month he been away, he found time to write to an unknown Oxford undergraduate, apologizing that he had not replied before and assuring the nervous young man that he would 'gladly' see him. (2) Hopkins had explained that he had decided to become a Roman Catholic but wished to know what it would be his moral 'duty to hold on certain formally open points' as he had no wish to embrace 'a minimising Catholicism'.

He felt it would be 'the greatest privilege' to be able to see Newman. 3 On 22 September Hopkins wrote an account of his visit to his friend Robert Bridges

. He was clearly pleasantly surprised that far from being earnest and solemn Newman was humorous and light-hearted:

'Dr. Newman was most kind, I mean, in the very best sense, for his manner is not that of solicitous kindness but genial and almost, so to speak, unserious. And if I may say so, he was so sensible. He asked questions which made it clear for me how to act; I will tell you presently what that is: he made sure I was acting deliberately and wished to hear my arguments; when I had given them and said I cd. see no way out of them, he laughed and said 'Nor can I': and he told me I must come to the church to accept and believe - as I hope I do. He thought there appeared no reason, if it had not been for matters at home of course, why I shd. not be received at once, but in no way did he urge me on, rather the other way. More than once when I offered to go he was good enough to make me stay talking. Amongst other things he said that he always answered those who thought the learned had no excuse in invincible ignorance, that on the contrary they had that excuse the most of all people. It is needless to say he spoke with interest and kindness and appreciation of all that Tractarians reverence. This much pleased me, namely a bird's-eye view of Oxford in his room . 4

It was decided that Hopkins should return to the Oratory at the beginning of the next term in October to be received into the Catholic Church, and, 'since a retreat is advisable for a convert, Dr. Newman was so very good as to offer me to come here at Xtmas, which wd. be the earliest opportunity for it. He thought it both expedient and likely that I shd. finish my time at Oxford …' (5)

On 15 October Hopkins wrote agitatedly to Newman from Oxford about his parents' 'terrible reaction to his letter informing them of his conversion to Rome. His parents wanted him at least to wait until the end of the academic year, but since Hopkins was not prepared to wait that long, it seemed pointless to wait any longer and he asked Newman to receive him without further delay. Newman replied consolingly: 'It is not wonderful that you should not be able to take so great a step without trouble and pain.' 6 And he agreed to receive him without delay on 21 October. At the beginning of December Newman told Hopkins that, since his family were now more reconciled to his conversion, 'home is the best place for you' during the Christmas vacation; he had only suggested a Christmas retreat in case Hopkins could not go home, but there was no hurry about that; Hopkins's 'first duty' was to get a good degree and show his family that his becoming a Catholic had 'not unsettled' him in his 'plain duty'.

As to the vocation he felt to the Catholic priesthood, it was best not to hurry a decision – 'Suffer yourself to be led on by the Grace of God step by step'. Ultramontane

fellow converts, like Archbishop Manning,

would have greatly disapproved of what they would have seen as his worldly advice to Hopkins to stay at Oxford and concentrate on his degree, and of his lack of zeal in not urging the young convert immediately to enter a seminary or religious novitiate.

Nevertheless, although Newman thought that Hopkins ought if possible to spend Christmas with his family, he had no intention of trying to frustrate a young man's vocation, and so instead he invited him to spend a week before the next term began, explaining kindly: 'I want to see you for the pleasure of seeing you - but, besides that, I think it good that a recent convert should pass some time in a religious house, to get into Catholic ways .' (8)

Newman had had it in mind to offer Hopkins a job at the Oratory School on his getting his degree at Oxford, but it seems that the latter had expressed a dislike of schoolmastering. However, when Newman heard that Hopkins had been offered a job at a tutoring establishment, he wrote to say that he thought Hopkins would be better off being in a religious house. He was, of course, alluding to Hopkins's possible vocation. And so Hopkins came as a master to the Oratory School on 13 September 1867.

When Hopkins returned home for the Christmas holidays he evidently wrote to tell Newman of his desire to test whether he had a vocation by going on retreat. On 30 December 1867 Newman wrote to advise Hopkins to take advantage of the School Easter retreat and to consult the priest giving it. In a note to Hopkins in February he kindly assured him that he need not make up his mind about whether to stay at the Oratory School till Easter, when he would be free to go or to stay. The retreat during Holy Week was given by a Jesuit, Fr Henry Coleridge.

Hopkins stayed on at the Oratory for Easter and then left for good. A fortnight later he began another retreat at the Jesuit novitiate. He knew he wanted to be a religious but was undecided about whether he had a Benedictine or Jesuit vocation.

In May he wrote to tell Newman he had decided to become a Jesuit, and apparently apologized that his vocation was not to the Oratory. He received in return a very characteristically nuanced but kind reply from Newman: 'I am both surprised and glad at your news. I think it is the very thing for you. You are quite out in thinking that when I offered you a "home" here, I dreamed of your having a vocation for us. This I clearly saw you had not , from the moment you came to us. Don't call "the Jesuit discipline hard", it will bring you to heaven. The Benedictines would not have suited you.' (9)

Hopkins and Newman continued to keep in touch by letter. In September 1870, Newman wrote to congratulate him on taking his first vows as a Jesuit. We have a surviving letter from Newman to show that by 1873 Hopkins had begun the practice of writing to Newman on his birthday, the 21 st of February. In September 1877 Newman wrote to congratulate Hopkins on his ordination to the priesthood. In his turn Hopkins wrote to congratulate Newman on being given the Red Hat in 1879. After receiving Newman's refusal of his 'complimentary proposal' in 1883 to write a commentary on the Grammar of Assent , Hopkins denied it was intended simply as a compliment. Newman responded: 'In spite of your kind denial, I still do and must think that a comment is a compliment, and to say that a comment may be appended to my small book because one may be made on Aristotle ought to make me blush purple!' 10

Ten years earlier, however, when Hopkins was reading the Grammar of Assent (which had been published three years earlier), he had written critically if somewhat obscurely of its style: It is perhaps heavy reading. The justice and candour and gravity and rightness of mind is what is so beautiful in all he writes but what dissatisfies me (in point of style) is a narrow circle of instance and quotation - - in a man too of great learning and of general reading - quite like the papers in the Spectator and a want, I think a real want, of brilliancy . But he remains nevertheless our greatest living master of style . and widest mind. (11)

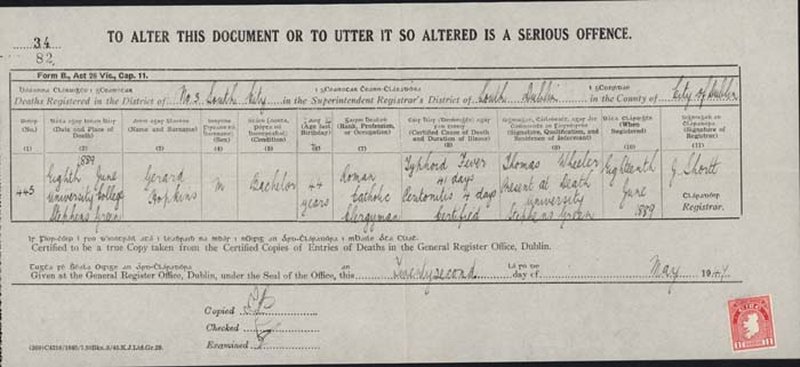

On 30 January 1884 Hopkins was appointed Professor of Greek at University College, Dublin

, which the Jesuits had taken over from the bishops who had thus re-named the ill-fated Catholic University of Ireland, the founder and first president of which was Newman. Hopkins arrived a week later to take up the appointment. A couple of weeks later he wrote to Newman for his birthday on 21 February. The date was perfect as Hopkins must have been anxious to tell his spiritual hero that once again he found himself teaching in one of the two educational establishments founded by Newman.

I am writing from where I never thought to be, in a University for Catholic Ireland begun under your leadership, which has since those days indeed long and unhappily languished, but for which we now with God's help hope a continuation or restoration of success.' He reported that the buildings on St Stephen's Green had 'fallen into a deep dilapidation' - 'Only one thing looks bright, and that no longer belongs to the College, the little Church of your building, the Byzantine style of which reminds me of the Oratory and bears your impress clearly enough.' (12)

The aged Cardinal wrote back briefly: 'I hope you find at Dublin an opening for work such as you desire and which suits you. I am sorry you can speak of dilapidation.' 13

There was a difference between the two men's reactions to Ireland. While Newman certainly had his difficulties with the Irish bishops he made a number of friends there and appreciated the very different qualities of the people from the English. Hopkins, on the other hand, felt an exile as the only English Jesuit stationed in Ireland where the English were the traditional enemy. The different attitudes to Ireland are well brought out in an 1887 letter from Newman to Hopkins, who had evidently written complaining about the state of rebellion in Ireland. He begins by acknowledging, 'Your letter is an appalling one - but not on that account untrustworthy'; but he then reminds Hopkins, 'There is one consideration, however, which you omit. The Irish Patriots

hold that they have never yielded themselves to the sway of England and therefore never have been under her laws, and never have been rebels.' Newman concludes the letter with a remarkable admission considering that he was now an eighty-six year old cardinal: 'This does not diminish the force of your picture - but it suggests that there is no help, no remedy. If I were an Irishman, I should be (in heart) a rebel. Moreover, to clench the difficulty the Irish character and tastes is very different from the English.' 1 Given the huge respect Hopkins had for Newman, both a religious teacher and as a writer, albeit of prose, we should not be surprised to find some influence on Hopkins's poetry. The 'terrible' sonnet, beginning 'No Worst, there is none. Pitched past pitch of grief', continues in the next line, 'More pangs will, schooled at forepangs, wilder wring.'

In his critical edition Norman H. Mackenzie

glosses this as 'woes experienced before weigh more heavily', and quotes from what is probably the best of Newman's Catholic sermons, which we know Hopkins knew, 'Mental Sufferings of Our Lord', where the preacher points out that 'the memory of the foregoing moments of pain acts upon and (as it were) edges the pain that succeeds'. (15) For lines 9-10 of the same poem, 'O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall/ Frightful, sheer .', Mackenzie

cites this parallel from Newman's poem The Dream of Gerontius : 'as though I bent/ Over the dizzy brink/ Of some sheer infinite descent;/ . for ever . falling .' (16) In his discussion of the 'terrible' sonnet beginning 'Not, I'll not, carrion comfort, Despair, not feast on thee', Mackenzie cites a sentence from the last chapter of Newman's Apologia pro Vita sua on the infallibility of the Church as an analogue to the sestet's 'mixed emotion, drawing spiritual triumph from material and emotional defeat': 'the human intellect . thrives and is joyous, with a tough elastic strength, under the terrible blows of the divinely-fashioned weapon, and is never so much itself as when it has lately been overthrown.' 17 For the words in the second and third lines, 'these last strands of man/ In me or, most weary, cry I can no more ', Mackenzie refers the reader to the passage from The Dream of Gerontius already quoted, which begins with the words, 'I can no more'. 18) Mackenzie's point about the 'mixed emotion' in the sestet of 'Carrion Comfort' has, as he points out, not only a Newmanian ring about it but describes a spiritual experience known, for example to St Ignatius Loyola, the founder of the Jesuits, and to St Thomas à Kempis.

But here I would like to suggest is where we can detect the very strong influence of Newman, in whom the idea of succeeding through failure is a pervasive theme.

In his biography of Hopkins, Robert Bernard Martin

writes: 'A year after arriving in Dublin Hopkins was beginning to console himself with that most dangerous of comforts, that it is better to fail than to win, and for his example he chose Christ, whose career ("he was doomed to succeed by failure") he invoked in writing a consoling letter to [Richard Watson] Dixon

when the Canon did not get the Chair of Poetry at Oxford.' (19) The actual letter to the Anglican Dixon was actually written in the summer of 1886, and the passage referred to by Martin is clearly the kind of spiritual advice a priest might write.

The trouble with secular, post-Christian biographers like Martin is that they are simply unable to take religion seriously as a powerful motivating force in a person's life. So here a spiritual and theological point which Hopkins knew was a favourite theme of Newman, whose own life was marked by a series of disappointments and failures (including the ill-fated Catholic University of Ireland), has to be given a purely psychological interpretation - and judged to be bad psychology. The idea of succeeding through failing is an idea we find in Newman without any such psychological significance as Martin attributes. Thus in a letter written at the height of The Oxford Movement

in 1834, five years before he began to have doubts about the Tractarian position and seven years before the censures on him by church and university authorities, we find Newman making the general point that if the champion of a cause 'loses . his cause . gains - this is the way of things, we promote truth by a self sacrifice'. 20

At the same period of Tractarian

confidence and progress, he wrote in a hostile Evangelical magazine that the Tractarians were happy 'to give a witness and to be condemned, to be ill-used and to succeed '. 21 For Newman this was not just a debating point but an important truth based on the fact that the Cross of Christ led to the Resurrection: 'it is a profound gospel principle that victory comes by yielding. We rise by falling.' (22) As a Catholic, he wrote: 'I know well, that, as to myself, all through life, when I have been despised most, I have succeeded most.' (23) Later, at a very low point, he again insisted: 'from the first is been my fortune to be ever failing, yet after all not to fail.' 24 Pace Martin this is not just cheap consolation: Newman was serious about the succeeding, not just the failing. He applied the same lesson - it is 'the rule of God's Providence that we should succeed by failure' 25) - to the Catholic Church which had 'a continuous history of fearful falls and as strange and successful recoveries'. 26) In the Anglican Parochial and Plain Sermons , which he preached in St Mary the Virgin, Oxford, and with which Hopkins as an ardent Anglo-Catholic must have been very familiar, the theme of success through failure is a recurring one. 'We will be content,' he preached, 'to believe our cause triumphant, when we see it apparently defeated.' What was true of the Church was also true of the individual believer: 'We advance to the truth by experience of error; we succeed through failures . Such is the process by which we succeed; we walk to heaven backward .' Christians 'seem to fail', but in fact they 'rise by falling'. The Bible, Newman stressed, shows how 'God's servants, even though they began with success, end with disappointment; not that God's purposes or His instruments fail, but that the time for reaping what we have sown is hereafter, not here .' He insisted, 'the good cannot conquer, except by suffering. Good men seem to fail; their cause triumphs .' 27)

In his main Anglican work of ecclesiology, Lectures on the Prophetical Office of the Church , Newman invoked the classic principle that 'the blood of martyrs is the seed of the Church' to argue that for the Church, which 'is ever in its last agony, as though it were but a question of time whether it fails finally this day or another', 'if death itself may be a victory, so in like manner may worldly loss and trouble, however severe and accumulated'. (28) The idea of success through failure is at the climax of Hopkins's longest and most ambitious poem, 'The Wreck of the Deutschland '. Persecuted by Bismarck's Prussia, five Franciscan nuns were on their way to a new life of nursing in the New World when their ship was shipwrecked off the coast of another unfriendly Protestant country. But in this tragic disaster, the poet sees a triumph, the triumph of martyrdom. The tall nun is depicted by Hopkins as a martyr, when she cries to the 'martyr-master', ''O Christ, Christ, come quickly.' Far from there being any need to postulate a miraculous apparition, as some commentators have done, 29 to do that would surely be to miss the point Hopkins is making - which is that in embracing willingly her cross and associating it with the passion of Christ, she bears witness to Christ her Master: 'The cross to her she calls Christ to her, christens her wild-worst Best.' Hopkins sees the nun as accomplishing far more by her death than she could ever have done as a nursing sister in America. For now she is a martyr who has entered Heaven, and as one of the saints can intercede for Hopkins's heretical countrymen and pray for their conversion: 'Dame, at our door/ Drowned, and among our shoals,/ Remember us in the roads, the heaven-haven of the reward:/ Our king back, Oh, upon English souls!'

The poem Hopkins considered his best, 30) 'The Windhover', also ends, according to Norman Mackenzie, with a reference to 'the sacrificial death of Christ, from which golden glory [that is, the Resurrection] resulted: 'and blue-bleak embers, ah my dear,/ Fall, gall themselves, and gash gold-vermilion.' (31) And Robert Bernard Martin

himself agrees: 'my own reading of it agrees with that group of critics who see in it transformation accomplished by reduction or destruction, precisely as Christ's glory was accomplished by His physical death.' 32 For Hopkins as for Newman, through the failure that surpasses all other failures, the Crucifixion, came the success that surpasses all other successes, the Resurrection. That was the supreme model to which both men looked for the idea of success through failure. Indeed, their own lives well exemplified the dictum, although success came sooner for Newman than for Hopkins. After the condemnations of Tract 90 and years of vilification for his alleged treachery as a Tractarian to the Church of England, as well as for his defection to Rome, followed by years when he was under a cloud at Rome, years during which his Ultramontane opponents did everything they could to frustrate him, finally in 1878 Newman returned to Oxford as the first honorary fellow of Trinity, his undergraduate college, and a year later to Rome on his elevation to the College of Cardinals. Hopkins, on the other hand, never lived to see his recognition as one of the major poets in the English language. Indeed, most of his poems remained unpublished in his own lifetime, including his major work, 'The Wreck of the Deutschland .

Ironically, it was Newman's longest and most ambitious poem, The Dream of Gerontius , that was not only published in the Jesuit magazine The Month in 1865 by its editor Fr Henry Coleridge

but achieved instant popular success. The poem today is mainly known through Edward Elgar's great oratorio, but no one would claim it was a great poem, although it contains an excellent theology of purgatory. Sadly but inevitably, Hopkins's 'Wreck of the Deutschland ' was rejected eleven years later in 1876 for publication by Fr Coleridge; it was a bitter disappointment, of course, for Hopkins, although Coleridge can hardly be blamed for not comprehending such a strange and eccentric poem at the time. Coleridge was Hopkins's oldest Jesuit friend and indeed the first Jesuit no doubt he had ever met when Coleridge had come to the Oratory School eight years earlier to give the Easter retreat. Still, success was to come, although it took another thirty years after Hopkins's death for his friend Robert Bridges to bring out the first edition of his poetry.

Notes

- Further Letters of Gerard Manley Hopkins including his Correspondence with Coventry Patmore , ed. Claude Colleer Abbot (London: Oxford University Press, 1956), 21. hereafter cited as L 3.

- The Letters and Diaries of John Henry Newman , ed. Charles Stephen Dessain et al. (London: Nelson, 1961-72; Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973-), xxii.289. hereafter cited as LD .

- L 3, 22.

- The Letters of Gerard Manley Hopkins to Robert Bridges , ed. Claude Colleer Abbot ((London: Oxford University Press, 1955), 5. Hereafter cited as L 1.

- L 1,6.

- LD xxii. 301.

- LD xxii.324.

- LD xxii. 327.

- LD xxiv. 73.

- LD xxx. 191, 207.

- L 3, 58.

- L 3, 63-4.

- LD xxx. 317.

- LD xxxi.195.

- Norman H. Mackenzie, ed., The Poetical Works of Gerard Manley Hopkins (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990), 451, citing Michael Moore, Mosaic , 12.4, 1979, 40. Hereafter cited as Mackenzie.

- Mackenzie, 452.

- Mackenzie, 455, citing Apologia pro Vita sua , ed. Martin J. Svaglic (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1967), 225.

- Mackenzie, 456.

- Robert Bernard Martin, Gerard Manley Hopkins: A Very Private Life (New York: G. P. Putham's Sons, 1991), 396. Hereafter cited as Martin.

- LD iv. 308.

- John Henry Newman, Via Media (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1899), ii. 159. All references to Newman's works, unless otherwise stated, are to this uniform edition.

- LD viii. 166.

- LD xvii. 49.

- LD xviii. 271.

- LD xxx. 142.

- LD xxviii. 91.

- John Henry Newman, Parochial and Plain Sermons , ii.93, v.107-8, vi.319-20, viii.130, 141.

- John Henry Newman, Lectures on the Prophetical Office of the Church , 355, 13.

- See Mackenzie, 343-44.

- Martin, 263-4.

- Mackenzie, 384.

- Martin, 264.

Links to Hopkins Literary Festival 2007

Elizabeth Bishop and Hopkins Poetry

Aubrey de Vere and Gerard Manley Hopkins

Patrick Kavanagh and Gerard Manley Hopkins

Communion of Saints in Hopkins Poetry

Place of Church in Hopkins Juvenile Poems

Cardinal Newman and GM Hopkins