D e s i d e r a t a

Thomas McCarthy, OPNewbridge College,

County Kildare

The rainbow shines, but only in the thought

Of him that looks.

‘IT WAS A HARD THING’

- GMH The Major Works,

Oxford’s World Classics, 2002, Oxford, 29].

This work is from now on called [‘Oxford’.]

When Jesus saw two men following him, he turned and asked, ‘What are you looking for?’ They said, ‘Rabbi, where do you live?’ His answer was: ‘Come and see’ [cf Jn 1:37-39]. Straightforward. They were anxious to know something...

I am not sure they really wanted to know where Jesus lived, but when you are caught off-guard while 'looking'/seeking to learn without being noticed, some answer will come out of your mouth. Perhaps they did not know what they were looking for, but there was a certain interest being shown in Jesus and in what was happening near Jesus. For one thing, that 'wanting to know' was a kind of desire. There is a variety of desires!

1. Desire to be able to express the questions and answers of life in a way that invites/provokes further discussion;

2. Desire to be a poet;

3. Desire to be a disciple of Jesus, or at least to hear him out as he proposes a way forward in human living.

Rise again: yes, you shall rise again, my dust, after a short rest.

Life that cannot die.

Life that cannot die – this will be given you by the one who called you.

Aufersteh'n, ja aufersteh'n wirst du, Mein Staub,

Nach kurzer Ruh'!

Unsterblich Leben! Unsterblich Leben wird der dich rief dir geben!

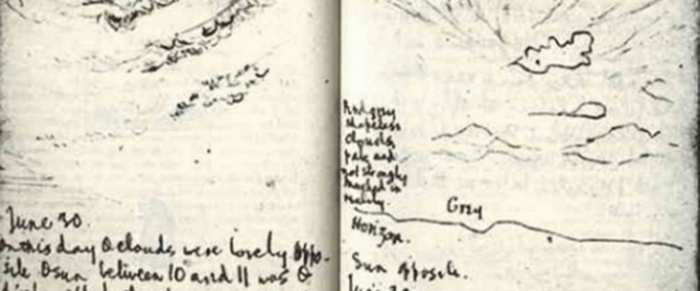

At any rate, desire does come into it: The rainbow shines, but only in the thought Of him that looks. When Augustine was teaching in Milan in the early 5th century after Christ, he often attended Liturgy in the Cathedral, and this was before he was admitted into the Church through baptism. The initial attraction of the Cathedral was an interest in the supposedly fine speaking skills of Bishop Ambrose. A desire to find out (a) if what he had heard about Ambrose was true; and (b) what it was that was being spoken about. The reason the young man from Hippo Regius then kept coming even long after being impressed by the preacher’s oratory was the content of his sermons and crucially how this substance of the message came closer than other philosophical theories he knew in seeking to meet and satisfy his own desire.

Did Augustine learn how to be a disciple of Christ and a member of the Church during the sermons of Ambrose? Not really: that instruction was conveyed by a variety of teachers, and there was a variety of reasons that enabled the lesson to be learned. What he was convinced of in Milan (he was baptised there, by Ambrose, in 387) was that the project of life (and an understanding of life's meaning) proposed by the Christians made sense to his enquiring and uneasy mind - uneasy but full of hope, rich, precisely, in desire. He found in Ambrose’s reading of the gospel message a framework, a pattern of thought (and of logic) that enabled him to speak meaningfully (within himself, to begin with) as he sought a path. It can be a Your dead shall live, their corpses shall rise./ O dwellers in the dust, awake and sing for joy!sermon or a series of spoken reflections on the biblical texts that enable us to ask questions. Or a single text, a fragment even of a poem, that sets us on a new path. And that can mean setting you out on your way as a poet of words, or a composer of music, or a disciple of Christ. 'I think I know what the question is. But the answer?'

Gustav Mahler could not reach a satisfactory solution to a question that tortured him for close to six years late in the 19th century: how do I complete my Second Symphony? A new language was needed to match his desire to say something, something else, something he knew his skills in writing for instrumental ensembles alone would leave unsaid. The death in 1894 of the notable and influential conductor Hans von Bülow greatly affected Mahler. At the funeral, he heard a setting of Friedrich Klopstock’s Die Auferstehung. ‘It struck me like lightning’, Mahler wrote, ‘and everything was revealed clear and plain.’ He knew what he wanted to say in the last movement, but lacked the tools, the words, until he heard that poem. He just knew he could not end the piece instrumentally.

He wants to speak, in words, about the beauty of afterlife, of some kind of transcendent renewal of life. The Klopstock text provided the vocabulary to inspire notes, harmonies, rhythms and sensations. Rise again: yes, you shall rise again, my dust, after a short rest. Life that cannot die. Life that cannot die - this will be given you by the one who called you. Aufersteh'n, ja aufersteh'n wirst du, Mein Staub, Nach kurzer Ruh'! Unsterblich Leben! Unsterblich Leben wird der dich rief dir geben!

But how do you awaken from the death that is so central to our existence? The Hebrew prophet Isaiah had courageous and faith-filled words in the 8th c. before Christ:

Your dead shall live, their corpses shall rise. O dwellers in the dust, awake and sing for joy! And Klopstock then, as we heard: Rise again: yes, you shall rise again, my dust, after a short rest.

Words like these can cause nerves to go on edge and/or lead to a marked change of heart-beat. But what I want to note here is that they do respond to a desire within, and so we are attracted rather than repelled. When the realisation comes to you that you have discovered the key (or map) that 'opens' the path ahead, then what happens next ... happens. You don’t have much choice when you are convinced within about what to do, what to say, where to go. It reminds me of Martin Luther’s ‘Hier stehe ich: ich kann nicht anders!’ The hope in your heart, the desire and growing conviction about something, sends you in a specific direction, and it would be unnatural even to attempt to divert. Klopstock continues, and Mahler sets these words too: With wings which I have won for Mit Flügeln, die ich mir errungen, myself, In heißem Liebesstreben, In love’s fierce striving, Werd'ich entschweben I shall soar upwards Zum Licht, zu dem kein Aug' gedrungen!

To the light which no eye has penetrated! That striving, that search for language in which to frame the meaning of life as we currently see it: such striving is associated with love. And it enables an ascent out of darkness. For Hopkins the (loving) Spirit of God lies at the heart both of search and discovery - and of knowing the search must continue, interrupted by occasional fresh (yet as black as ever) darkness and ‘not-knowing’. What Hopkins (and each Christian) is seeking will, perhaps unknown to us for a time, remains 'unfound' years after we begin the search: the desire we are speaking of cannot be fully satisfied in this life. And in Hopkins' understanding the Spirit enables mind and heart to rise above what is held firmly by earth and seems to know no ascent. Hence sensual gross desires,1

IL MISTICO

Right offspring of your grimy mother Earth!

My Spirit hath a birth

Alien from yours as heaven from Nadir-fires. …

But foul and cumber not The shaken plumage of my Spirit’s wings.

But come, thou balm to aching soul, Of pointed wing and silver stole,

With heavenly cithern from high choir, …

Be discover’d to my sight From a haze of sapphire light,

Let incense hang across the room

And sober lustres take the gloom; …

When strangely loom all shapes that be,

And watches change upon the sea;

Silence holds breath upon her throne,

And the waked stars are all alone.

Come because then most thinly lies

The veil that covers mysteries;

And soul is subtle and flesh weak

And pride is nerveless and hearts meek.

Touch me and purify, and shew Some of the secrets I would know.

It's best at least to know you are in the dark! The Hebrew Psalm 130 pleads with the Lord God: Out of the depths I cry to you;. The question marks, the unknown, that seek to keep us downstairs, in the dark, these are the uncertainties that it’s best to admit to, and some light may then enter, though please God not enough at once to blind us! But the desire of a disciple is there in Hopkins, and persists. His wanting to destroy the poetry of his pre-Jesuit days indicates also how contrasting he sees the opulence of words and the (strikingly 'opposite') poverty of Christ’s humility.

It can take time for a disciple to realise that, while contrasting the world and God in some sense, some wisdom will say that it is God who in the end makes sense of the world, and of poetry. Was it perhaps a more realistic focus of his desires that later led Hopkins to realise poetry could still form part of the search party that sought life's meaning and the best path to take? But what more can be said about ‘learning’ to be a disciple, a poet who speaks the Spirit of Christ?

‘Give love to anybody crossing your way’, suggests the preacher, ‘and you will thus be touched by the love of God’. You come to faith not principally through a series of logical rational deductions but by an immediate contact with, touch, feeling of the world, the world as a gift from God, true sign of the presence of God through the personal presence of Jesus Christ. [Jesus touches those who need healing: they recognise that this man is aware of their desire for healing, and the touch meets that desire and enables them to feel and be considerably healthier.] Hesse wrote:

The touching, the healing: Du kennst mich wieder, You recognise me, du lockst mich zart. you beckon gently; Es zittert durch all meine Glieder my limbs tremble deine selige Gegenwart. with your blessed presence.

What may impel a person toward an urgent sense of the need for reform, for realignment of priorities, a change of direction, may be the impact even on our bodies of what troubles us in spirit. A sensation that indicates something deeper… The incarnation must be decisive in the disciple too. Our being real flesh, planted on this earth! Permit the evidence of the senses, ‘the feel’ of what we ought to do, to be part - at least - of the energy that impels one's inner self forward toward a baptismal font or a particular formulation of faith, of hope and of love. But for all the revelation of meaning, of wisdom, of God, it is the hiddenness of God that can inspire either Elijah’s silence before the ‘still, small voice’ or the hesitant poetry of partial living. [Vasser Miller has: Somewhere between silence and Ceremony springs the Word.] The search, the learning about poetry or discipleship, is somehow bound to fail! Sense is made of it all when we in our turn are, finally, 'senseless'. Only when a sense of being ‘done’, complete, even exhausted, comes upon us may we say to our hands ‘Cease your doing’, to our brow ‘Forget all thought’: is it perhaps when we realise how elusive the object of desire remains that we grow - and it's an interesting word for this characteristic - we grow 'philosophical'? Then, and only then, is our soul ‘unguarded’, unearthed, and may soar free in flight (cf Hermann Hesse, for instance, in Beim Schlafengehen). A heap of helplessness - heavy clouds of unknowing... It is as we conclude our searching and die that we begin to realise or truly learn we have perhaps not even scratched the surface of what it was we wanted to say, to think. A ruin. A scattering. What we sought to gather as a collection of words or ideas that gave a modicum of wisdom, is then scattered. It can all break down before our eyes - all that seemed to make sense might come together in 'a heap of helplessness', of nonsense insofar as long-term meaning is concerned.

But we continue to desire, to ask - even the question mark on our face at the moment of death is recognition of what life is, this life, and what it is not and cannot hope to be. A question remains… A symphony can occasionally be asked to close on an up-beat! ‘Come and see, said Jesus to those who wanted to know more about him and asked him where he lived. I was present at the ordination of two of my Dominican brothers to the priesthood, in Dublin, just two weeks ago. Part of the ceremony sees the Archbishop of Dublin explain pretty well the classic and challenging role of the priest in the Christian community. Then he asks the candidates, ‘Do you understand what you are undertaking?’ And they reply that they do, and they answer in the affirmative in all honesty.

The truth is they can't quite know or understand what they are undertaking, certainly not in a way that will be the case years later. But their desire to be, to do and to know: this is sufficient. [Rather like Jesus asking someone who was ill, 'Do you want to be well again?' Has the man who has been ill considered, for instance, how he will earn his food? Up to now, people in their generosity have given him something - seeing his ill-health. But if he is bouncing about, he will have to get busy!] The disciple's search goes on, as does that of the poet. It is to some degree a search in a haystack, or into what Desmond Egan calls the universe of things and all the inbetweens where God is hiding. [Hopkins in Kildare 32. This work is henceforth called H in K.] Themes that recur then include the journey from darkness toward light. I will say a bit about Hopkins' juxtaposition of the observance of Lent and the celebration of Easter. A feature of his poetry is the contrast between the Church season of Lent (particularly its penitential features) and the April sense of growth and new life. 'At last I hear the voice I knew' (A VOICE FROM THE WORLD [Oxford 42]) might be Hopkins'summary of what happened to Mahler. In coming across the text of Klopstock's Die Auferstehung, Mahler somehow discovered a language in which to speak what he knew and began to realise the sense it made. In our case, it could be in the cacophony of too much sound that we cannot quite identify a voice or a message. Thus it can be that from what we call a 'Lenten silence', something emerges into view from the fog and into our ears from the pregnancy and possibilities of silence. Birthday and Risen Life.

In A COMPLAINT [Oxford 77], Hopkins at one point says 'Our sex should be born in April perhaps or the lily time, But the lily is past, as I say, and the rose is not in its prime. He would like his birthday to have been close to the time when we celebrate the Resurrection of Jesus, I dare say. Rather, as he laments

In A COMPLAINT

'Think this, my birthday falls in a saddening time of year'... Gather gladness from the skies; Take a lesson from the ground;

Flowers do open their heavenward eyes

And a Spring-time joy have found;

Earth throws Winter’s robes away,

Decks herself for Easter Day

And if he doesn’t mind when his birthday is, he can say:

Make each morn an Easter Day [Oxford 84].

But Easter is not a perfect time but only its beginning, its spring. I quote Des again here: after the rites of another summer even the sun is tired and all is not as well as it seemed in May. [H in K, 20] There are occasions when a disciple would have to say that all is not as well as it seemed on the day of baptism or ordination. The search goes on: the Church is a community of believers, of sinners who know what needs to be done about it, and that Christ is the saviour, who is as energetic on our behalf as he is merciful towards us! This community of believers could be like a society of poetic minds, who assist each other with words to put black-and-white ideas into revealing colour! The Word became Flesh. And the memory the disciples shared of that Flesh became the words of the Gospels - and of the Church's constant silent and aloud contemplation of these texts. 'Let a man's life be praised in so far as he asks for pardon' - words of the same St Augustine. Pardon perhaps also for imagining too early we had understood the meaning of it all! Hopkins wrote, while speaking of Christ: His point is humility and witness: through our sins, as long as we recognise committing them, we are those who as well and the same way demonstrate and fairly show the love of God our forgiver. There is so much to ask, to discover, to learn - and thus to unlearn too. And there is so much to learn to remember, and some to learn to forget! There is an occasional moment when the impression we have is one of having arrived, having understood… And thank heavens our knowledge of ourselves and of the universe expands when we realise we have only partially grasped the elusive nut we thought we had cracked. Egan again: because there always are always must be other words other sounds other signs other openings onto the face the movement the transsubstantial lodging beyond saying leaving us tonguetied again baffled again defeated again to begin again try to catch to snatch at life ah life… [Des Egan, IN OTHER WORDS - H in K, 11.] And yet for some there are incidents (perhaps repeated) that lead to a reduction of a sense of hope or optimism - for some perhaps the sense of diminished desire. Listen to the words of the poem by Johan Runeberg, set to music by Jean Sibelius. SE'N HAR JAG EJ FRÅGAT MERA (SINCE THEN I HAVE ENQUIRED NO FURTHER) Why is springtime so fleeting, Why does summer last no longer? This I often used to wonder, Asked of many, but got no answer. Since my loved one has failed me, Since his warmth has turned to cold, All his summer turned to winter, Since then I have not asked again, Only sensed, deep in my thoughts, That the beautiful is perishable, That the lovely will not last. So even when disappointment comes, it brings what we also term a 'thought', 'sensation', even if it is not a joyful one or one we had been hoping to experience. Jesus' Death; Our Life For the Christian disciple, like Hopkins, it is not only a matter of there being death and also the hope (or assurance) of life hereafter.

For Gerard the Jesuit the whole matter is bound up, front to last, with Jesus: his life, his death, and then…

O Death, Death,

He is come.

O grounds of Hell make room.

Who came from further than the stars

Now comes as low beneath.

Thy ribbed ports,

O Death Make wide; and Thou,

O Lord of Sin,

Lay open thine estates.

Lift up your heads, O Gates;

By ye lift up, ye everlasting doors

The King of Glory will come in. [Oxford 61]

I would be sure of this: it’s more pleasant to read Hopkins' poetry than his sermons - certainly when the theme is death and/or life! There is something frightening (unnecessarily so) about the lines I will now quote [from Oxford 295-300].

'Death is certain and uncertain, certain to come, uncertain when and where… I see you living before me, with the mind's eye, brethren, I see your corpses: those same bodies that sit there before me are rows of corpses that will be. And I that speak to you, you hear and see me, you see me breathe and move: this breathing body is my corpse, and I am living in my tomb.

This is one thing certain of your place of death; you are there now, you sit within your corpses …

Look no farther: there where you are you will die.

I see little if anything in these lines of the 'Do not fear sentiment often on Jesus' lips. O schöne Zeit, o Abendstunde!

For Hopkins and the Christian tradition, it is Jesus' life-long dedication - until and including a death that we believe he saw (at least partially) as a sacrificial offering to God on behalf of sinners - this means that we reflect not only on the Morning of Risen Life and the Empty Tomb but also on the Evening (any evening, in fact), the peace that evening brings, evening in the sense of the close of life, the sinking of the living but tiny planet that each of us is. I return again to a poem set by Jean Sibelius, this time the work of Aukusti Valdemar Forsman, entitled

TO EVENING, ILLALLE

Welcome, dark, mild and starry evening!

Your gentle fervour I adore and caress the dark tresses

That flutter round your brow.

If only you were the magic bridge that would carry my soul away,

No longer burdened

By the cares of life!

And if it were the happy day when, overcome with wearyness,

I might join you when work is over and duty done,

When night unfolds its black wings and a grey curtain falls over hill and dale,

O evening, how I would hurry to you!

You can only truly be optimistic if the one you are setting out to teach actually wants/desires to learn, only someone who knows she/he does not yet understand what they are being invited to learn. Our energy seeks language and light.

The prayer of a

person who in this way seeks language might be like what

Hopkins wrote in IL MYSTICO: [Oxford 8] Touch me and purify, and show

Some of the secrets I would know.

The springtime that marks the end of Lent and the opening of the Easter season is there as a hinge for much of Hopkins' imagination. And then there is the concept of evening. Hopkins’ words from SPRING AND DEATH are inviting: It had a dream. A wondrous thing: It seem'd an evening in the Spring. Finally, I go back further than Sibelius or Mahler. I go back to The Passion of our Lord Jesus Christ according to Matthew, by Johann Sebastian Bach, and specifically to a poem to evening that is included.

Given how much of the Passion Drama took place at eventide, the inclusion of the poem is fully justified. It was evening when Jesus was gathered with his disciples for what we now call The 'Last' Supper. It was evening the following day when the soldiers knew that it would be offensive to Jewish observance of Sabbath to leave the body of executed prisoners hanging where they had died. Picander [Henrici, 1700-1764] speaks of the sense of joy, of completion, that evening brings. He notes how much took place either in the evening or near to it, and sees a pattern to justify his speaking of the evening as 'schöne Zeit'.

In the evening, when it was cool, Am Abend, da es kühle war, Adam’s fall was manifest; War Adams Fallen offenbar; In the evening the Redeemer cast Am Abend drücket ihn der Heiland him down nieder. In the evening the dove returned, Am Abend kam die Taube wieder And carried an olive branch in its Und trug ein Ölblatt in dem Munde. mouth. O schöne Zeit, o Abendstunde! O beautiful time! O evening hour! Der Friedensschluß ist nun mit Gott Peace is now made with God, gemacht, For Jesus has endured his cross. Denn Jesus hat sein Kreuz His body comes to rest. vollbracht. Ah, dear soul, prithee Sein Leichnam kömmt zur Ruh, Go, bid them give thee the dead Ach, liebe Seele, bitte du Jesus, Geh, lasse Dir den toten Jesum O wholesome, o precious keepsake! schenken, O heilsames, o köstlichs Angedenken!

Peace is now made with God, for Jesus brought his cross to

completion.

What is not complete for my colleagues in the

Church - and was not complete in Hopkins - was the perfect

union with, understanding of, the Lord and Meaning of all, the Word that started it all and will likely sing Amen at some point.

But not yet!

The time for waiting is still showing on the clocks of our enquiring minds and hearts. Hopkins too knows the full revelation will dawn - but not yet. His heart has desires yet, and so retains its 'joint search', as it were, with an enquiring mind.

George Bernard Shaw

said: We don't stop playing because we grow old; we grow old because we stop playing

But not yet, then! His heart's desire is elusive still. Then, to behold Thee as Thou art,

I'll wait till morn eternal breaks {Nondum Oxford 83Links to Hopkins Festival Lectures 2014

Gerard Manley Hopkins Correspondence