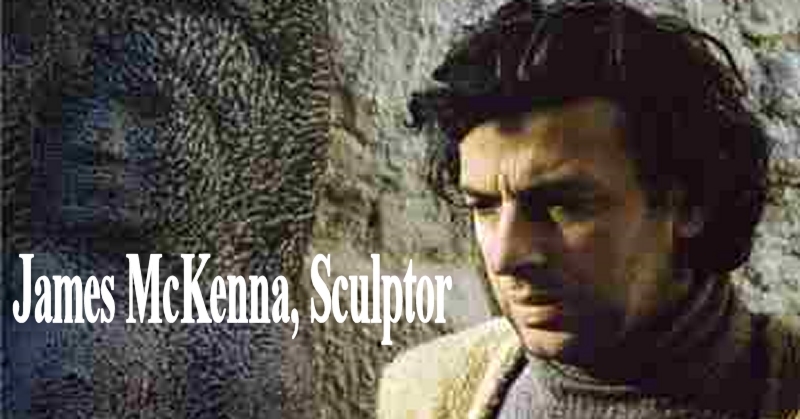

James McKenna, above all else, a Sculptor, a Stone Sculptor.

Nowadays the term 'Renaissance man' seems to be often used - but of James McKenna, it could accurately be used. Best known as a sculptor, he also deserves attention as a visual artist, playwright, poet, intellectual activist, musician and cultural theorist. Ireland has more than her fair share of intellectuals without an intellect; McKenna was an intellectual with an intellect; one to whom ideas were alive and crucial; perhaps one of the most vital and influential Irish artists of the 20th century.

James was firstly and pre-eminently a sculptor. Here he enjoyed the high regard of his contemporaries and it is here that we must begin to assess his achievement. (1)

James never abandoned the Figure

The most obvious quality of James's sculpture is its figurative element. Through the turbulence of abstract art, performance art, conceptual art, hyper realism, what we might call discovered sculpture, street furniture... the post-structural with all the baggage of the Surreal and especially of Dada which these vogues carried with them, James never abandoned the figure.

As Brian Fallon said in opening the James McKenna Exhibition at The Riverbank Arts Centre in Newbridge on September 15, 2003, he hasn't dated. The Modernists of his day look 'old hat' now

At a time when it was 'un-cool' to stay with the Figure, James McKenna stayed with it; at a time when experiment (the more outlandish the better) and instant shock were the vogue, James stayed within the mainstream of sculpture: that line stretching back through Giacometti to Rodin to Michelangelo to Romanesque and Gothic to Celtic and Early Christian back to the Greeks and Praxiteles and beyond them to the Egyptians.

To be wholly original is to be Wholly Bad

Of course the beauty of his actual work is crucial: the carving of exquisite fineness, painstakingly carried through, always in the service of a vision. Looking at his sculpture, one recognises something unique: he had achieved his own style. Take The Hopkins Monument in Monasterevin

, for example.

Here we encounter a McKenna characteristic: time and again his work offers a contrast between an almost rough-hewn appearance on the one hand, and carving as exquisite as that in those faces. Take another, more recent, example: his Warriors of Banba arriving at Dublin Castle (1999)

of huge branch-like figures, the almost abstract monumentality of which is counterpointed by faces of surprising delicacy. Oftentimes, the legs of his carvings have this kind of fineness, unexpected especially within his larger scale. I suggest that this is at the core of the McKenna vision: a mixture of strength and vulnerability finely balanced within the one figure; and for all the overwhelming dignity of that figure, it is a tragic vision, with a sense of human impermanence at its heart. This magnificent Group was exhibited at Dublin Castle in September 2001. (Given that Banba is an old Irish name for Ireland, the irony of the situation was not lost on McKenna).

Not that James McKenna's work lacked an experimental side - far from it. I believe that his greatest work and the measure of his genius

(a word used by Patrick Murphy, Chairman of The Arts Council when he opened a McKenna Exhibition (at the Gerard Manley

Hopkins Literary Festival , 2000) can be glimpsed in the way he managed to stay within a tradition and yet expand it, combining

it with a search for something new. (2)

A Willingness to Experiment

One is always conscious of a willingness to experiment in his work; if anything, this newness became more and more marked with the years. A thing must be itself before it can take on any symbolic resonances - and James knew this - but he was 'modern' in his awareness that material itself must be respected, acknowledged even, before it can begin to transcend itself. In his work, wood is allowed to be wood and stone, stone. No effort is made to pretend that the material used is anything else. I believe that with the passing of years, he tended more and more to reverence the actual material used - and, by acknowledging it, to involve the viewer in the drama of seeing it take on another life.

Oisín Caught in the Time Warp

That last, wonderful group in Sligo: Oisin for example (disgracefully allowed to rot away by that County). For the Oisín figure, he bolted together timber planks, shaped and fashioned painstakingly. He even employed boat-building techniques to construct the huge belly of the horse, keeping it hollow so that dancers might emerge from it and perform. (5) Truly it is one of the most breathtaking sights in Irish sculpture.

Oisin Caught in a Time Warp

had a happier fate. It is now splendidly displayed in Arus Chill Dara, the Administrative Office of Kildare County Council.

Here, the magnificent physicality of the horses and their largeness does not exclude a conceptual element: the earth itself as chariot, the wheels of which are just emerging. The giant figure of Fergus, though broadly figurative, does not aspire to any naturalism and actually involves a recognition by the spectator that this is wood and not pretending to be anything else. The sculpture is finally about spirit, not body. Perhaps it avoids the now- dated dualism implicit in such a distinction so that the whole group is both recognisable and transcendent at one and the same time. This is the McKenna note and the measure of his achievement. Such a complex effect could only emerge through an artistic vision; through the integritas of the artist. (3)

James McKenna - an Irish Feeling for Nature

Other examples come crowding in: the amazing stick figures in his Grianán piece from Fernhill, 1993. They carry the figurative freight but clearly draw attention to their material as part of the experience. A reminder, too, of James's Irish feeling for nature. Time and again, figures emerge from and sink back into the material out of which they are created - or perhaps I should say, in which they are discovered. This became one of James's master themes, and a very Irish one. Irish myth is redolent of such Celtic animism. According full respect for the material as material is really central to this theme.

Note in this example the different kinds of finish in the piece, all within that reminder of its wooden parabola: fromthe exquisite carving of one figure to the almost unfinished look of another. (In some respects, the piece can seem like a mini history of modern sculpture). The Warriors of Banbha, 1999 Examples of the synthesis achieved by McKenna abound.

The Host of Banbha Exhibited in Dublin Castle

These would include one of his last group-pieces, exhibited in Dublin Castle in 1999: The Host of Banbha; and his two wonderful Famine sculptures, one of which (due to the far-sightedness of our Arts Officer) is located at the Hospital in Athy. The other Famine carving suggests with poignancy the willingness of nature herself - as Corn Goddess - to intervene and offer sustenance to a child dying of hunger. More than half of this last piece is abstract, non-representational - drawing attentionto its material and delighting in it. The Gerard Manley Hopkins Monument

These are real achievements and we could linger much longer on them and on other such but let us now consider his major public sculpture in Co. Kildare:

Note the title, for a start.

A recent study of Hopkins in Ireland describes the monument as 'Miss Cassidy' on one side and 'Hopkins' on the other (the plinth, central both to the piece and to an understanding of the concept, is not mentioned). This is NOT Hopkins, nor Miss Cassidy. A work of art, it transcends such literal - mindedness (the kind of approach which would totally identify the protagonist in some of his dark sonnets with Hopkins himself: the equivalent, perhaps, of identifying the actor who plays King Lear as the King and being surprised to find him having a fry for his breakfast the morning after the performance).

The Monument is rich in allusive meaning: the male/female (Early maquettes of the piece and am impressed by the way they each turn their own way, and away, even in James's earliest grapplings with the concept); artist (with book) and his muse (with flowers); river and human impermanence (remember the setting, above 'the burling Barrow brown' - and James's tendency to personify rivers); Ireland/ England (a continuing preoccupation for both Hopkins and McKenna); even the whole question of vocation and sacrifice...

One will not exhaust the reverberations of this work. The plinth in the middle - a lectern for a reading or lecture - with the kingfisher of inspiration from one of James's favourite poems (4) draws the whole magnificent conception, both delicate and massive, together. (A sculpture of which Monasterevin and Kildare can feel proud and which James almost literally donated to the Hopkins Summer School).

The massiveness of this group draws attention to another aspect of much McKenna work: its sheer size. James of course made many small pieces - I own a tiny, exquisite, bronze horse four inches high - but in general he tended to opt for monumentality. Much of his sculpture is huge: the Education Group (1983) in Limerick University; his Grianán Figures; the Sligo group; the

Warriors of Banba arriving at Dublin Castle (1999 which he exhibited in Dublin Castle in 1999; various standing figures including the 2 metres high bronze couple (in a private collection) the St. Martin de Porres Monument (commissioned by Fr. Harris O.P. for the Claddagh Dominican Church in Galway); Wise Ailbhe of the Fianna (private collection); Conaire Mór ; the female figure which was erected over McKenna's grave in Kilbelin Cemetary, Newbridge ... and, above all, his horse and rider, Oisín Caught in the Time Warp (1996).

Standing sixteen feet high and weighing perhaps five or six tons, this last piece took five years to complete. As we can gather from it and from other such pieces, size was a major preoccupation for James - so important, in fact, that he was prepared to follow through on these giant conceptions at the risk of never finding a venue for them, much less a buyer. (One thinks of his being refused entry to the Municipal Gallery for a huge horse; of his having to exhibit the Oisín monument in the courtyard of the RHA Gallery; and his

Warriors of Banba arriving at Dublin Castle outdoors).

James Understood the Dramatic Impact of Size

Better than most, James understood this dramatic impact of size - Brian Bourke suggests that 'drama is the basis of art' - and the poignancy that can be achieved through the mix of delicate carving and massiveness. There is drama of a different kind here too - and perhaps an analogy might be made with a play which invites audience participation, without scenery and the other rituals of theatre. As well as such considerations, I feel that James wished to defend the frailty of his figures, his sense of how vulnerable we all are, by the counterpoint of hugeness. There can be no art without compassion and I find such compassion in the way James employs hugeness of bulk and counters it with carving of exquisite delicacy; fragility defended by size. Like Beckett characters, or those of Sophocles, say, relentlessly reduced to their very essence, these McKenna figures manage to project with almost unbearable feeling, the irreducible dignity of the human. All his figures have this qualityDesmond Egan 20 September, 2003and along with it a kind of stillness which places them almost outside of time and change. His work, like that of all true artists, is a dialogue with time: an attempt, in Patrick Kavanagh's words, to Snatch out of time the passionate transitory

.

McKenna's Epic Vision

There is another, related, consideration: James McKenna had the epic vision. He thought in terms of all history, of all that could be known - and he had the greatness of spirit to tackle the largest view of things possible. This at a time when, with all the self-questioning of the various art forms, with all the agonising over the possibility in a barbaric century of continuing at all, with all the angst which typifies 20th century art - when most of us were battling within the narrowest of limits and the tiniest of ambitions - James McKenna reveals his amazing hope and his refusal to be browbeaten by the meaner assumptions of mean times. James McKenna's was an epic vision (The amazing range of interests revealed by his library show clearly his wish to know as much as possible about world history, its cultures and languages).

A word about his Watercolours and Drawings

Though James never held an Exhibition of drawings alone, his artwork is an important aspect of his creative spirit. One series of watercolours which he made over a period of about two years just before and after he came to Kildare seems very accomplished to me. Here again, we can identify something of his style inthe tendency, already noticed and in evidence here, to focus on some aspect of the work, leaving the rest in a kind of creative suggestiveness. Unfinished, one might begin to say, until we see that the poetic ambiguity of the part contributes to the impact of the whole - even more, is essential to it.

In this picture, for example, the lovely allusiveness of colour and form help to highlight the energy of face and gesture, deepening the expressiveness of the whole. There is drama in it, too, as again, McKenna draws attention to the fact that colour and shape are only a gloss on the feeling, inviting us to remember that this is a creation. Coleridge talks about 'the willing suspension of disbelief' at the heart of theatre; McKenna is modern in his not asking for such suspension of disbelief: the emotion and vision sustains this picture through our awareness that it is a manufactured rectangle, worked on.

Of course James throughout his life made many drawings and sketches, some of great beauty. Over-all, I think his artworks betray the hand of a sculptor in their feel for mass, volume, dimensionality - and also in the delicacy of their line, as if the activity of drawing made someone more accustomed to hammering very aware of the gentle, even evanescent, possibilities of the purely visual.

James McKenna, dramatist, poet

James McKenna has not in recent times received enough recognition for his written work - though Brendan Behan asked him to write the film script for The Quare Fellow and he did. James's own play, The Scatterin' , was the major hit of Dublin Theatre Festival in 1960, drawing full houses every night and transferring to London's West End for another five-week run. It received superlative critical acclaim '...the most exciting Irish play since The Plough and the Stars

. The Scatterin'

is above and

beyond criticism' . (Séamus O'Kelly, Drama Critic, The Irish Times)

.

The English Spectator

critic had equally high praise:

The Scatterin' has many rare virtues.Mr. McKenna's lyrics have a bite and compassion which are the nearest

things to Brecht I have seen written in English.

Fergus Linehan

wrote of it,

The most exciting play written by an Irishman sinceWaiting for Godot... here is dialogue of a richness that only Brenda Behan of our modern writers can match. The Scatterin' is not just the play of the Festival or of the year but of the decade.

Brian Bourke

said of the play (in an RTE programme) that James 'got the balance between the burgeoning youth not allowed to bourgeon and the other Ireland which was equally ignored and dying...in the fifties and sixties . . . '

Who else at that time even approached such a theme? The Scatterin'

was not only Ireland's first Rock musical, a minor classic (6) regularly performed by Dublin amateur groups; it can also be credited with having paved the way for films such as Roddy Doyle's The Commitments

and the genre of working class Dublin novels popularised by Roddy Doyle and others.

Why did The Abbey Theatre refuse to Commission James McKenna - despite his success with The Scatterin'?

Was James commissioned by our National, heavily subsidised, Irish Theatre to write a play? No chance. (With little conviction, they staged his At Bantry in 1967 in the Peacock Theatre; and there was a revival of The Scatterin' in1973. Apart from that, nothing: they even lost one of the playscripts he submitted and in general steadfastly ignored him.

On occasion, he picketed the Abbey in protest). He had employed the mask, to notable effect, also exploring the demands of verse-speech, dance and dialogue in At Bantry

. This play deals with the abortive French expedition to Ireland in 1796 and encapsulates some of McKenna's fierce republicanism and pride in the Irish. The performance which I attended in The Peacock

during its perfunctory two-week run (without the dance element) which it received in August 1967 did give a glimpse at times of that 'magic sorrow' of which the author later wrote in his preface to the published text - and the chorus there (dropped and then chopped in the half-hearted Abbey production) was 'the first in the history of Irish drama'.

James wrote more than 20 other plays, two of which - Hotep Comes from the River and At Bantry won awards (at Listowel and at the 1916 Commemoration competitions, respectively) but he became frustrated by the lack of opportunities to stage modern drama in Dublin and tried to solve the problem by forming, in 1969, his own modest, unsubsidised, theatre company, Rising Ground .

James McKenna and Experimentation

McKenna staged experimental mask plays, mostly biting satires on contemporary politics and on the Dublin arty, bourgeois, scene; all of them written by himself. Actors were amateur; the 'theatre' no more than an upstairs room (in Westmoreland Street) ; and the seating - for about 25 - could be described as spartan. Yet for all that, and a constant lack of funds, James kept the flag of experimental theatre flying in Dublin and his savage onslaughts on politicians and establishment figures was every bit as exciting - and as necessary - as those of the Kavanagh brothers in Kavanaghs Weekly had been in 1952.

(One of the playlets which I particularly remember, Keep Paddy at the Mixer , on the theme of exile, highlighted the insensitive comment of the then Minister for Foreign Affair, ' We can't put barbed wire round the Mailboat '). Of course, like the Kavanagh broadsheets, (I nearly said broadsides), McKenna's plays won him no friends among influential people and the fledgling Arts Council, many of whom he lampooned in a way reminiscent of Aristophanes. Agamemnon Won't You Please Come Home , published by James at his own expense, was - as he put it —' more light of foot' and written to the beat of the American Civil War ballad When Johnny Comes Marching Home

.

Even here, with a larger cast than audience, McKenna exploited the strange poignancy of the mask to real effect - certainly one of the few Irish dramatists to do so. Those masks, painstakingly made by James himself, were themselves things of beauty, like Japanese Noh masks. His dramatic adaptation of Hopkins's The Wreck of the Deutschland

was performed at The Hopkins Literary Festivall 1998 outdoors with masks and employed stylised action and costume, on a stage built by James himself and with his taking part, proved a highlight of the Festival.

Modern Irish theatre may not be heavily in debt to James McKenna—but it does owe him something: a spirit of experimentation and of adventurousness and a willingness to embrace contemporary issues with courage. A history of Rising Ground

will probably never be written; it should be.

McKenna the Musician

His songs for The Scatterin'

and elsewhere are memorable. At their best, they embody his own energy and themes. Mostly, he adapted the words he wrote to Irish airs (as Tom Moore did) but sometimes he composed the tune as well - as for the haunting Maeve's Song :

I went with my love and loved him freely, /But that was in the night; / In the morning sun I met him early - / He did not think it right.

A memorable song, full of the complications of male/ female attitudes to love. Brian Bourke, in his talk about James as 'The Giant on my Shoulder ' describes another song ' Willie Gannon ' in the same play as ' an original sean-nós '. My favourite McKenna song comes from the play Ulster Lies Bleeding . This was performed in the Project Theatre in 1972, a year after Bloody Sunday: a mask play, in verse, with choral odes; dealing with the decadent politics of Northern Ireland.

Dance of Death

The dance of art

Sounds like a dirty word;

In the public mind

An image blurred.

The public men

Who lead this mind about

Its love repress and cut it out

And people feel this impulse not their own;

A poor winged bird to commerce thrown.

From active day on into space of night

In each man's mind the bird takes flight-

And on it flies

And takes the man along -

The very man who mocked his song.

A rapparree the bird will long remain:

Survival's song; the people's pain.James was a fine singer; to hear him sing this song was an experience you would never forget.

As well as songs, James also wrote poems from time to time, throughout most of his life. As one might guess, they have the typical McKenna mix of passion and social awareness, with a sharp contemporary ring.

A Collection was published by The Goldsmith Press Ltd. in 1973 (a reprint is planned) and contained a memorable poem on the theme of exile,

Oxford Street is long;

Oxford Street is long;

Oxford Street is long

And I'm not strong . . .I believe that this poem, with its complex mixture of bewilderment, loneliness, loss and anger, and its insight into the exile experienced by so many Irish and others, may stand the test of time. A keen student of the Irish language James also wrote quite a few poems in Irish. James McKenna, politician, activist The Greeks called someone who took no part in public life an idiotes: an idiot; James could never have been accused of 'lying low'.

On two occasions he ran in the General Elections and in 1976 in Local Elections when he campaigned vigorously for the formulation of a Culture policy. He was one of the founder members of The Independent Artists Group, which held its first Show in 1960. We have seen something about his drama group, Rising Ground . He was an active and vocal member of

Aosdánaand the first to propose to them a Culture Policy involving all the arts.Aosdánanever even debated his paper, nor took his proposal seriously - still, like all good ideas, it made its own way and lately The Arts Council has been much exercised in drawing up a Culture Policy, the core of it along lines first proposed by McKenna; one more area in which he was a prophet without honour. In 1996 he and I founded the Samhildánach Group, dedicated to the ideal of maintaining artistic standards over a broad spectrum of the arts; it lasted for three years; the minutes of our meetings were kept by James and they make for lively reading.James McKenna, Unselfish Contribution to Culture

In all of these activities, James made a real and unselfish contribution to Irish cultural life. As he put it himself, talking about his own efforts and those of supportive friends, What we did wasn't merely to bring about improvement in the structures for the arts - and it met with considerable resistance - but we expressed a commitment to a broad creative ethos that had its base in Ireland. (Statement for a Catalogue, 1993). As much as he did in any of these formal activities, James informally energised his friends in the arts; (enlightening us, lambasting us; driving us on; and always inspiring us by) with what the painter John Kelly described as ' a kind of brutal integrity, a total belief in himself as an artist '.

I have said little about that integrity— a word which crops up again and again inJames McKenna: A Celebration.James was simply unable to compromise— not for a sale or commission; not for a word from the media; not for favour fromthe critics.He paid the price for this: an austere life verging on poverty - but those lucky enough to know him admired him as a person as much as we admired his art— and would have been easily persuaded that the two were not unrelated. Every real artist is a major presence. If the difference between a major artist and a minor one is a matter of his or her influence on others—and it is— then I would conclude by saying that James McKenna was a major artist, a genius by whom I believe our age may yet be judged. I for one would be happy with that.

Notes

Desmond Egan was an acquaintance and then friend of James for almost 40 years— since we first met in Brian Bourke's house in Booterstown Avenue in 1963.

Such a quality may equally be found in the work of some of the great writers: in Hopkins's poetry, for example, which represents both a harking back to and a daring move away from the older poetic forms e.g. the sonnet, which he almost re-invented. People have often commented on James's utter integrity as a human being: the word crops up regularly in the Celebration collectionrecently published in his honour, but what I have in mind right now, in the purely artistic context (insofar as such a thing exists) is the vision which saw that piece through, the fruit of 3 years work.

(4) James McKenna quoted to me the line 'The just man justices' with great feeling, a few weeks before he died

Whenever I brought out anyone to James's workshops, after he had put the piece together, I asked him/ her to close their eyes while I drove up beside it. When they looked, there was always a gasp. Why has it not been performed in Kildare? It would make a lively change from the tired procession of Joseph and his etc. Jesus Christ Superstar and their ilk—not to mention the plethora of plays by Friel and MacDonagh. The previous year and during that one, international visitors also listened enthralled to his recital, masked, of some Hopkins poems.